Margaret Ludwick spends her days sitting in a wheelchair at a senior care center in Elkhorn. She never speaks. The only expressive motion involves her hands—she constantly puts her long, tapered fingers together like a church steeple. Her big blue eyes stare straight ahead but focus on nothing. No one can reach her anymore, not her daughters, not her husband.

Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia in adults 65 and over, robs even the most intelligent people of their brain and eventually destroys their body. There is no cure. There is no pill to prevent it. There’s not even a test to definitively diagnose it. Effective treatments have proven as elusive as the disease, itself.

“We do have medications that may help with symptoms in some patients, especially in the early stages of Alzheimer’s,” says Dr. Daniel Murman, a specialist in geriatric neurology at The Nebraska Medical Center. “But they don’t truly slow down the disease process.”

According to researchers, the number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s will triple in the next 40 years, which means 13.8 million will have the disease by 2050 (Chicago Health and Aging Project research as reported by nbcnews.com).

Awareness of symptoms is crucial for early intervention.

“Memory loss and changes in behavior are not a normal part of aging,” stresses Deborah Conley, a clinical nurse specialist in gerontology at Methodist Health Systems who teaches other nurses and caregivers about Alzheimer’s. “I would urge family members to take [their loved one] to a family physician first, seek as much information as possible, and start making your plans.” An assessment that includes the person’s medical history, brain imaging, and a neurological exam can result in a diagnosis that’s about 85 percent accurate for Alzheimer’s.

Ludwick, a registered nurse, who worked at Immanuel Hospital for years, never received an extensive workup.r

“I would urge family members to take [their loved one] to a family physician first, seek as much information as possible, and start making your plans.” – Deborah Conley, clinical nurse specialist in gerontology at Methodist Health Systems

r“I first noticed something was wrong about 15 years ago, when Mom was 70,” explains Ludwick’s daughter, Jean Jetter of Omaha. “It was the day I moved into my new house. Mom put things in odd places, like a box labeled ‘kitchen’ would wind up in the bedroom. And she stood smack in the middle of the doorway as the movers tried to carry large pieces of furniture inside, and she just stared at them.”

As Ludwick’s behavior grew worse, Jetter begged her father, Thomas, to get her mother help.

“He didn’t want to hear it. He kept saying, ‘This will get better.’ He had medical and financial Power of Attorney. Dad worked full-time, and she was home alone. This went on for eight years.”

Ludwick’s steady decline rendered her unable to fix a meal or even peel a banana. She lost control of bodily functions. After she was found wandering the neighborhood on several occasions, Jetter was finally able to call Adult Protective Services and get her mother into an adult daycare program. After breaking a hip two years ago, Ludwick arrived at the Life Care Center of Elkhorn.

“This is such a sad, but not unfamiliar case,” says Conley, who began working with Alzheimer’s patients in the mid-’70s. “Even in 2013, people do not know what to do, where to turn.”

Dr. Murman adds, “There is still a stigma attached to Alzheimer’s. People don’t like to hear the ‘A’ word. But it’s much better to be open and specific about it.”

A specific diagnosis may rule out Alzheimer’s.

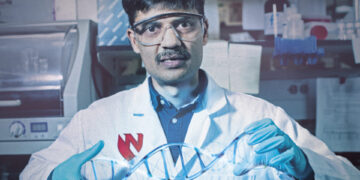

“Depression can mimic the symptoms of Alzheimer’s…symptoms like mistrust, hallucinations, apathy, social isolation,” explains Dr. Arun Sharma, a geriatric psychiatrist with Alegent Creighton Health. “But we can treat that. We can treat depression.”

Dr. Sharma helped establish a 22-bed, short-term residential facility called Heritage Center at Immanuel Hospital to better diagnose the reasons for a person’s memory loss. Once a patient is stabilized and receives a proper care plan, they can return home. The more doctors learn, the faster a cure will come.

“I see something exciting in the next five to 10 years,” says Dr. Sharma. “If we identify and isolate the protein believed responsible for Alzheimer’s, perhaps we can do a blood test to catch the disease early.”r

“There is still a stigma attached to Alzheimer’s. People don’t like to hear the ‘A’ word. But it’s much better to be open and specific about it.” – Dr. Daniel Murman, specialist in geriatric neurology at The Nebraska Medical Center

rBut what about a cure? With 78 million Baby Boomers coming down the pike—10,000 of them turning 65 each day—this country faces an epidemic. And what about the psychological, financial, and emotional toll on the caregivers, who are very often family members? They, too, feel isolated.

“It was an impossible situation for me. I couldn’t get her the help she needed,” says Jetter, who bore the brunt of the family crisis since her married sister lives in Dallas. “Now that Mom is at [the nursing home], I can take a breather and concentrate on Dad, who also has mental issues.”

In recent weeks, her father, Thomas, has been admitted as a permanent resident of Life Care Center of Elkhorn as well.

What about her own family?

“I have no one. No husband, no boyfriend. I mean, what boyfriend would put up with all this?” asks Jean, who’s been shuttling between one parent and the other for years, all the while trying to run her own business. The situation has obviously taken a huge personal toll.

Conley has two words for anyone facing similar circumstances: Alzheimer’s Association. The Midlands chapter has support groups, tons of information, and can gently guide the adult child or spouse. They even have a 24/7 hotline: 800-272-3900.

For anyone dealing with Alzheimer’s, that number could become a lifeline.