Mention the term plastic or reconstructive surgery, and images of Cher, Botox injections, and liposuction to combat that extra 20 pounds that can’t be worked off come to mind. The procedure tends to be thought of as a luxury-ticket item. But in the field of otolaryngology (commonly known as ear, nose, and throat), plastic and reconstructive surgery has been used to give back basic functions such as swallowing or speaking.

“There’s been a lot of negativity in regard to plastic surgery, but plastic surgery has tremendous effects on the patient’s overall psyche, and when it comes to head and neck-related plastic surgery, we can actually restore a patient’s livelihood,” Dr. Oleg Militsakh said.

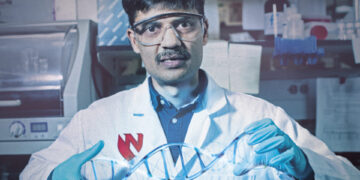

Militsakh is an otolaryngology surgeon at Methodist Health Systems. He’s also an associate professor of surgery in the department of surgery at Creighton Medical Center. He performs surgeries on cancerous and noncancerous tumors in the head and neck areas, and sometimes handles reconstructive surgeries that are needed because of such invasive operations. The challenges of his field, such as navigating through complex, dense areas of nerves within a small area, were a key reason why Militsakh chose this specialty.

“One single nerve can stop movement of your vocal cord, or tongue, or some other important vital structure,” Militsakh says.

Militsakh was born in the former Soviet Union in Minsk, the capital of what is now Belarus. He emigrated to the United States with his family in 1993 when he was 17. His parents were engineers in the Soviet Union. His mother’s focus was economics, his father’s was chemical engineering. In the United States, his parents first ended up taking minimum wage jobs. His family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, because other family members already lived there.

“There’s only one thing I knew about Kentucky: Jim Beam. I didn’t know about the Kentucky Derby. I didn’t know about bluegrass,” Militsakh says.

Militsakh studied at the University of Louisville and earned his undergraduate degree in chemistry and pre-med. He completed his medical degree at the University of Lexington in Kentucky. After graduating with his M.D., he studied otolaryngology, and head and neck surgery, at University of Kansas City Medical Center for five years.

He still was not done training. He spent one year in Charleston, South Carolina, where he studied microvascular and advanced head and neck reconstructive surgery under the direction of Dr. Terry Day, later the president of the American Head and Neck Society. The combination gave him a dual skill set that put him in demand. Offers for jobs came from North Carolina, Missouri, Kentucky, and other states, including Nebraska.

Methodist was one of the hospitals that Militsakh visited in 2007. During the visit, he struck a rapport with doctors William and Daniel Lydiatt. Militsakh found the brothers and medical professionals to be knowledgeable, trustworthy, and dedicated to their patients.

“What made the Omaha position different is that there were these extremely personable surgeons that have concentrated their efforts on very specific populations and by doing this without diluting their area of expertise, they became super experts in their field of practice and that resonated well with what I wanted to accomplish,” Militsakh said via email. “[I] wanted to continue to promote excellence in the field.”

Another reason for choosing Methodist was because the hospital’s signature blue matched the color of his beloved Kentucky Wildcats, Militsakh joked.

“That is the perfect blue,” Militsakh said.

Militsakh has performed thousands of thyroid and parathyroid surgeries. His focus also includes microvascular surgery, which involves transplanting tissues from other parts of the body to a patient’s head and neck areas. In one pediatric case, Militsakh used part of the bone of a boy’s fibula (the lower leg bone) to reconstruct his mandible (lower jaw).

Some surgical reconstructions wouldn’t have been possible 20 years ago. One of Militsakh’s favorite modern tools is an ultrasonic bone knife. The knife’s vibrations are so rapid that it enables surgeons to cut specific designs out of a person’s bone, almost like a jigsaw.

“It vibrates so when you touch the bone, it will cut the bone like a butter knife,” Militsakh says.

Before being referred to Dr. Militsakh, Sherry Shapiro lived with a tumor in her throat for almost 30 years. She guesses the most likely cause for her tumor was that when she was young, doctors radiated her tonsils to shrink them. In 1989, she met with Dr. Trent Quinlan, also from Methodist. For more than two decades, Shapiro underwent surgeries to debulk, or “cut away” the tumor. However, in 2016, after Quinlan performed yet another surgery, he determined he could no longer go down that path of care. Shapiro needed a total laryngectomy, surgical removal of her larynx.

The removal of Shapiro’s vocal cords wasn’t the only thing that concerned her: this surgery would be done by another physician (Militsakh). After such a long relationship with Quinlan, Shapiro was nervous about meeting her new physician. After her first meeting with Militsakh, she felt reassured.

“I just felt at peace. I knew he was going to take care of me,” Shapiro said. She noted that he was kind, “but he doesn’t sugarcoat the situation,” and she didn’t feel rushed when she was talking to him.

The surgery took more than seven hours. During the surgery, Militsakh used tissue from Shapiro’s thigh to “rebuild” her larynx. She was hospitalized for seven days with a feeding tube. After her release, she was on a liquid diet for a few weeks.

This March marks the third anniversary of her surgery. Today, she only sees Militsakh for an annual follow-up. Every three months, she goes in for a 15-minute procedure where her speaking valve is replaced.

“My voice sounds better now than before the surgery,” Shapiro said.

The time that would have been spent on additional surgeries is now spent working out (she exercises six days a week) and spending time with her grandchildren. Shortly after her surgery, Militsakh told her that they had successfully removed the tumor, and she was cancer free. After explaining the results to Shapiro, Militsakh spent a few minutes talking about the procedure to her grandson.

“I later asked him about that [conversation], he was such a busy man. [Militsakh] said ‘that could be a future doctor,’” Shapiro said.

r

Visit bestcare.org for more information.

rThis article was printed in the January/February 2020 edition of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.