Pharmaceutical drug commercials, they’re everywhere these days… Action!

Fade in. A dark cloud curdles over a suburban home. Sunken, briefly startled eyes retreat back into a thousand-yard stare. A bleating alarm clock melts into the sobs of a child out of frame. Drifting through motes of greyscale dust, a hand reaches languidly for the bedside curtains—then pauses.

“Does every day…feel more exhausting than the last? Is making special memories…just another chore? Is the view outside…always cloudy?” a clear, yet tender, voice probes. “Then you may be experiencing symptoms of depression…”

Overhead shot. An umbrella bursts open, revealing a yellow frowning face; garlands of rainwater spill over its cheeks and over the edge. Grocery bag in hand, the figure beneath pauses.

Cue music. Snare drums. Brass. Double time.

“Lexachant can help.”

The curtains snap shut…and the front door opens to a pair of mischievous grins. Four yellow rain boots kick up puddles as as the umbrella lowers.

“Call your doctor if you experience…” Cue list of side effects.

The family of three collides in a sopping, laughing embrace. Clouds break as the umbrella rolls into frame, a yellow smiley face sparkling a sun-slick canopy. Pan up. “Lexachant: Seize the Smile, Rain or Shine.” Fade out. And… Cut!

Depression, of course, is no laughing matter—in 2023, the number of Americans suffering from the condition reached a record-breaking 60 million individuals, or just under 18% of the population. The country, and indeed the world, has been described as enduring an “epidemic” of mental health crises, the human toll not only immediately devastating, but incalculable in the longterm.

Still, it’s worth examining pharmaceutical ads’ ubiquity and the predictable, practically memetic, cadence they’ve produced in the popular imagination. The stilted quality of their “candid” lifestyle scenes; the derivative, if occasionally surreal, themes and symbolism; the calm, assuring voiceover turned auctioneer at the first syllable of adverse reactions.

There’s something uncanny about these commercials, partly because this type of generic, suggestive advertising implies, but does not outright promise, desirable outcomes. In fact, the legality of direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising is more stringent than alcohol internationally. Only two countries, the United States and New Zealand, refrain from banning their syndication outright.

Of all the things left unsaid, however, perhaps the most jarring is how these drugs actually work. In the specific case of antidepressants, nobody, not even the world’s leading neurologists and psychoanalysts, can explain with certainty how they function—nor conclusively, to what extent.

The pharmacological thesis underlying their efficacy—the monoamine hypothesis, or in layman’s terms, mental illness as a consequence of chemical imbalance—was initially described following the synthesis of drugs intended to treat tuberculosis, their incidental “antidepressant” effects prompting a lasting rebrand. This premise was later refined and heavily marketed to the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) to push the first “blockbuster” antidepressant, Fluoxetine (Prozac), in 1988, before the medical community roundly rejected it around the turn of the millennium.

Despite this, an estimated 1 in every 8 Americans take antidepressants today, the loftiest new peak in a trend of prescriptions surging by 65% between 1999 and 2014. As of 2022, the antidepressant industry commands a $15.6-billion global market share, with North America leading a forecasted $23.22 billion by 2030. Needless to say, the ad campaigns have proven successful.

In 2022, the journal Molecular Psychiatry published a rigorous ‘umbrella review’ encompassing decades of relevant literature, which stirred something of a media frenzy when it declared what most academics had long surmised: the specific link between depression and serotonin volume is wholly unsubstantiated. The authors, apparently anticipating this response, added, “80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance.’ Many general practitioners also subscribe to this view and popular websites commonly cite the theory.”

They even went a somewhat controversial step further in their conclusion:

“…this belief shapes how people understand their moods, leading to a pessimistic outlook on the outcome of depression and negative expectancies about the possibility of self-regulation of mood. The idea that depression is the result of chemical imbalance also influences decisions about whether to take or continue antidepressant medication and may discourage people from discontinuing treatment, potentially leading to lifelong dependence on these drugs. […] We suggest it is time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression is not empirically supported.” (Moncrieff et al., University College London)

Yet antidepressants, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) the most readily prescribed, do appear to alleviate depressive symptoms in a small but not insignificant number of patients. According to yet another 2022 meta-analysis—which tabulated more than 232 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials submitted to the FDA between 1979 and 2016— approximately 15% of the 73,388 participants involved showed a significant therapeutic response to the ingredients beyond a placebo effect. Nonetheless, the authors cautioned that “the potential for substantial benefit must be weighed against the risks associated with the use of antidepressants, as well as consideration of the risks associated with other treatments that have shown benefits.” (Stone et al., FDA Division of Psychiatry and Johns Hopkins University).

Researchers have been quietly seeking a replicable explanation for years. A few positions have gained traction, but none the empirical heft required to tip the scales of consensus.

Outside the unexpected strength and indirect positive outcomes of placebos, those more critical of antidepressants’ mechanisms point to a general “numbing effect,” loosely supported by anecdotal patient reports and observed suppression of the amygdala, the two almond-shaped clusters of nuclei located deep in cerebellum. This part of the brain processes memory, decision making, and emotional responses such as fear and anxiety. Conversely, a handful of limited but compelling studies suggest the synaptic interplay induces a multimodal “downstream effect” that may also account for the two-to-three-week delay typical of relief: the enhancement of neuroplasticity, or adaptive structural changes to the brain. In other words, the revival of dormant neural connections in the brain.

Dr. Lou Lukas, an Omaha-based physician, professor, and clinical researcher, believes the latter theory holds merit. Although for her, a different drug has stolen the limelight.

In 1971, the compound in question was deemed a Schedule I-tier substance, which, according to the 1970’s Controlled Substance Act, possesses “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” and was therefore excluded from grant funding and laboratory testing alongside drugs such as heroin and quaaludes. After decades of sporadic evidence to the contrary, the red tape is finally beginning to peel.

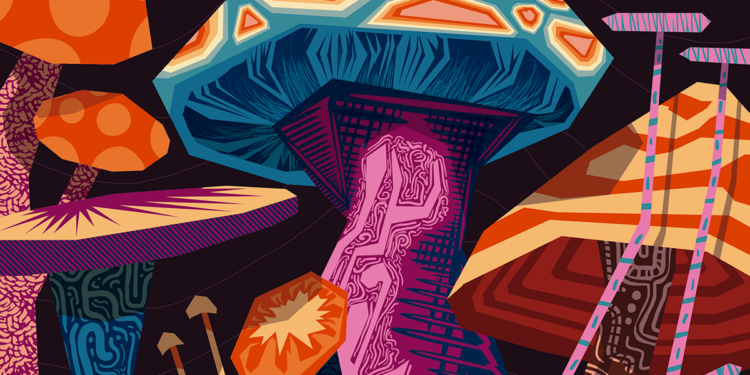

Psilocybin, a naturally-occurring compound found in over 100 species of fungi (“magic mushrooms”), received “breakthrough therapy status” for treatment-resistant depression in 2018 and for major depressive disorder in 2019. At this time, Lukas and her team’s exploratory pilot trial represents the first, and thus far only, federally-sanctioned investigation of the substance in Nebraska.

While psilocybin and other recently approved “breakthrough” psychedelics have never starred in focus-group tested, multi-million dollar television commercials, they’ve become the subject of renewed interest—and optimism—as promising data trickles in.

Besides, screen time isn’t recommended.

“If you have your eyes open, your brain is processing stimuli and trying to interpret it. When you close your eyes, all you have is what’s inside your head, and that’s where the therapeutic impact usually is,” Lukas advised.

Apertures

As the Chief of Palliative Medicine at the Nebraska Veteran’s Health Association, Dr. Lukas is well acquainted with the psychological pitfalls encountered by those approaching their mortality. As a study participant and eventual colleague of pioneering psilocybin researcher Dr. Roland Griffiths—whose landmark 2006 study all but jumpstarted the field—she’s equally familiar with the profound, potentially life-changing outcomes psychedelic-assisted therapy can support. It is the marriage of these experiences that colors her lessons from behind the lectern as an associate professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, and the portmanteau at the heart of her studies: Heartland Palliadelic Research Center.

“We’re 11-and-a-half years out and I can still describe minute by minute parts of the experience…I can feel that sense of awareness that you have of yourself […] a sense of identity that you just take for granted until you have this experience where you actually get a kind of ‘behind the scenes’ look at what’s going on,” Lukas recalled of the 2011 Johns Hopkins clinical trial that introduced her to psilocybin. “What I found, even though it wasn’t an explicit part of my psychedelic experience, I was practicing palliative medicine at the time, I just felt this sense that all is well. That this fear we have around dying, it’s okay […] and if we approached it with just a little bit more courage and a little more curiosity, it wouldn’t be as all-consuming and terrifying.”

Depressive and anxious episodes are understandably common responses to terminal illness diagnoses, the unpredictable temperature of stress responses and decision-making at times blistering with panic, other times glacial with detachment. While opiates and anti-inflammatory adjuvants are common prescriptions for physical pain, antidepressants are the go-to for psychological distress. Lukas’ pilot trial, which began enrolling participants last spring, aims to gauge the efficacy, pharmacology, and overall utility of psilocybin-assisted therapy for those facing a particularly lethal form of illness: pancreatic cancer. While recording neuronal activity and collecting experiential reports, she hopes the sessions do more than simply dull the pain experienced by patients and their families, but promote serenity, even joy.

“[Psilocybin’s active metabolite, psilocin] is the key that gets you in the door, and then these downstream effects unfold long after the drug is out of your system,” Lukas explained. “The neuroplasticity that happens, we think, persists for about a month after the altered state of reality, which is over in about six hours […] It’s creating an imbalanced state in the system that is temporary, but that imbalance causes changes in the way your brain is able to adapt to future things.”

Lukas noted that “imbalanced cells” are among the most significant differences between psilocin and serotonin’s interactions with key neural receptors, comparing the latter to driving with “one foot on the gas, one foot on the brake.” The former, meanwhile, hits the serotonin system like a hypersonic missile, pulling in and rearranging nearby receptors in its wake. Thus, the theory goes, neural connections are rapidly reestablished, even after a single session.

“When we think about this idea of neuroplasticity, think about when you’re born, when you’re a baby—you don’t have any connections that know how to do anything, right? Your whole childhood is spent figuring out which connections get you further down the road and which do not. Like, how many times does it take you to learn how to stand?” Lukas posited. “Well, while you’re doing that you’re tightening the connections that help you stand and throwing away the ones that aren’t effective.

“You’re slowly pruning the forest. By the time you’re an early adult, you’ve gone from being in a jungle to this really robust maple tree […] But then as you get older, some of the richness fades, you get stuck in your ruts, and you’re doing the same thing over again. And the older you get the more trauma you experience, and you move from a nice maple tree to a Joshua tree or a cactus and there aren’t many options […] and you can be stuck in maladaptive patterns. But under psilocybin, you can return to that jungle for a little while.”

As reflected in a growing body of research, the subjective aspect, or the “trip,” may be just as crucial to therapeutic outcomes as the biomechanics. Following three 90-minute introductory sessions, a standardized 25 milligrams of synthetic psilocybin—a “sweet spot” dose, as Lukas put it—is administered under vigil of two facilitators.

The patient wears a soft, grey blindfold.

“The interior world is more vast than you can imagine. I just had a study participant say in our trial, ‘I feel like I’ve lived my whole life in a utility closet. I didn’t realize I could just open the door and step out into an amphitheater. And not only is it an amphitheater, but you can sit in any seat and you can have any view you want,’” Lukas recalled with a grin. “There are things under the rug or in the basement that are yearning for your attention, that can’t find your attention because you can’t see them […] but when you can bring your attention to these things you’re able to find healing. A lot of what we do in these clinical trials is looking for tools to prepare someone to take advantage of that experience.”

While Lukas hones her research on psilocybin, she’s a firm believer in “psychedelic-assisted” as an umbrella term. From other “classical” compounds like LSD and DMT to “non-classical” drugs like MDMA and Ketamine, Lukas believes psychedelics have the potential to revolutionize treatment for a host of psychological afflictions when properly administered.

Beyond palliative care, early findings suggest psilocybin may also be effective in treating mood disorders, addictions, and possibly eating disorders. The results of a placebo-controlled study published in Nature Journal in May 2021 revealed that those treated with MDMA against a placebo for moderate to severe PTSD were twice as likely to recover, with an astonishing 71.2% no longer meeting the DSM-5’s diagnostic criteria by the end of the 18-week trial (Mitchell, et al. University of California, San Francisco). Now, MDMA is the first psychedelic in history pending review for full FDA approval.

“This whole idea that there’s a personality disorder, and there’s depression, and there’s anxiety, and there’s trauma…it’s quite useful to be able to categorize them in some way. It’s helpful to know a little bit of the differences, but underneath most of them, there’s probably a similar underlying neurological-psychological structure, and this gets to what we call a cross-diagnostic or trans-diagnostic approach,” she said. “It has different flavors, and it manifests in slightly different ways, but it’s the consequence of this reality model not functioning properly and not being adequately adaptive.”

Psychedelics, under professional care and sustained by cognitive therapy, have shown to recalibrate one’s “reality model” with few side effects, low toxicity, and virtually zero risk of physical dependence—by no means panaceas, but less risky for those who believe in such things. While “magical” might be a stretch, it’s hard to deny their transcendental qualities. For some, they can open fresh eyes of gratitude in the face death.

For others, they can break its seductive gaze.

Wide Angles

Note: Due to legal and privacy concerns, the names of subjects in the following sections have been altered to protect their identities.

“In late January we did psilocybin, and I did not know going into the psilocybin journey that it could be utilized as a treatment for depression,” said Jordan Martin, her husband, Nick, sitting next to her. “But it treated my depression. Nothing had treated my depression, and in fact, I did have a suicide attempt last summer. I mean, I was in a really, really dark place.”

Jordan described a number of physical sensations during the experience—shivering, shaking, crying, laughing. An enormous release of pent up trauma built over 18 years of treatment-resistant depression, then…

“I think it was like, three days after that experience,” she continued. “And my depression was gone. It was like, literally, clouds parting, blue sky, and a sun beaming through. It was just gone. It just vanished, and it was a miracle.”

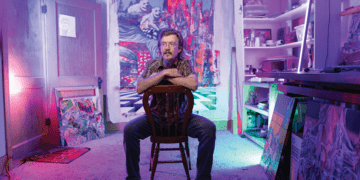

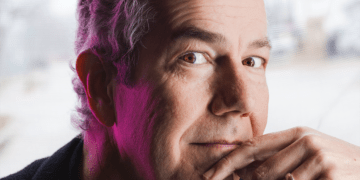

Dr. Lou Lukas

Photo by Bill Sitzmann.

The initial series of events that led to Jordan’s full recovery—from a form of depression that not only defied all conventional treatment, but would typically be described with terms like “chronic” and “lifelong”—are only marginally less remarkable.

Married for nearly 10 years, father to two young sons, a thriving small business under his purvey, a “like” on Nick’s Facebook page may well have been a “like” for the American Dream itself. Tragically, much of it was a dream, one that had all but faded to black years prior—an advertisement for a life already spent by domestic strife, the trials of parenthood, the unyielding pressures of business ownership, and walls thick with the miasma of mental illness.

Nick wanted to sell the business; Nick wanted a divorce. He couldn’t muster the courage to carry through with it. Then, a close friend and confidant suggested a way to find it, one he’d never considered before. Equal parts desperate and intrigued, Nick covertly made arrangements and embarked on a solo sabbatical out of state.

“I went to this experience expecting that I was going to divorce Jordan and sell the business. Like, that I was finally going to get the courage and the clarity that this is what I need to do,” Nick confessed. “And the experience was exactly the opposite…it became abundantly clear, during my experience, that Jordan was the love of my life, and despite how difficult our marriage was, Jordan and Nick were meant to be forever. And that I love my business and that it was meant to go on for perpetuity.”

The process itself begins with a battery of medicinal precursors, vitamins, minerals, and sessions with guides to frame goals and expectations. The primary medicine used: an injection of ketamine to the arm.

“It was like being shot out of a rocket for the first 15 minutes, seeing visuals and experiencing things I’ve never experienced in my life as I’m listening to music and have blindfolds on, and I’ve got a microphone attached to me, and for the next four hours it’s just a stream of consciousness,” Nick recounted. “Under the influence of this medicine, you’re going to talk for the next two to six hours and just have these calm ‘downloads.’ And then after the fact, you transcribe the entire recording—I listened to it, transcribed it, then I worked with an integrator afterwards to do something with this information.

“My friend said to me, ‘Your ego is the jailer of the soul,’ and the idea behind this outfit is that when your ego goes to sleep, love is what’s left […] It was a real shift in the direction of my life and in my relationships.”

Upon Nick’s return, Jordan was incredulous of the man who stood before her. The one who’d left had been furtive, irritable. Now, proclamations of love and renewed commitment sprang easily from the mouth that’d been tight-lipped mere weeks prior.

“Jordan wasn’t having it,” Nick said, recalling her words at the time: “‘I didn’t have this experience with you and I don’t believe you.’”

Still suspicious and having never experimented with psychedelics before, it took some coaxing from Nick before Jordan agreed to try MDMA as a couple.

“I’ve never considered myself a person who takes drugs, like, I smoked some pot in college, but never did drugs, never desired to do drugs, and you know, with MDMA being a rave drug, or party drug, that scared me a lot,” Jordan said. “But Nick wanted to do an at-home ceremony with the two of us […] and I had a call with the people who provided us with medicine and addressed a lot of my fears around the safety of the drug. That was my primary concern: safety.

“[Now] we refer to it as December 10, like it’s a holiday for us. It was so profound that it has its own name […] so we did the ceremony, December 10, and we were able to heal a lot of wounds in our marriage. Yet, I was still depressed…”

And a just over a month later, she wasn’t.

“I think that our society just wants to run and take pharmaceuticals, and that dampers our ability to experience true joy, we’re just trying to numb ourselves,” she said. “This mode of treatment (psychedelics) is not numbing. It’s facing and truly processing and integrating your trauma and how you got to where you are. And that’s real growth.”

Jordan and Nick plan to continue exploring different “rabbit holes” of their lives via psychedelics. Willed by a promise made at his grandmother’s deathbed, Nick untangled decades of bitter resentment—stemming from a cycle of abuse that saw him channeling his father’s abuse toward his younger brother—during a sibling MDMA ceremony. Still, regardless of these outcomes, the couple cautions moderation and respect for the power of these substances.

“We’re huge advocates for the medicines, and they’re extremely powerful, more powerful than we realized when we started taking them,” Nick said. “When we started, were like, ‘Man, everybody should do this! And then as we got into some of the deepest, darkest, trickiest stuff, we started to change our minds […] This should really be done in the hands of experienced professionals, not recreationally on your own just for fun.”

Dark Room

It was a cold September night when Marie Ledger found herself tramping over brackish leaves and spindly branches toward the dark maw of Elmwood Park’s southern entrance. About 45 minutes before, she and two of her best friends had excitedly passed around ziplock baggies, an earthy scent preceding hasty mouthfuls of “magic mushrooms.” It was their first time, and she reassured them of the great things to come.

But now, though the stars shown bright in the waxy night sky, she couldn’t seem to shake the darkness that stalked the tree line, nor the grasping squelch of mud that pulled at her sneakers. As the green arches of the swing set came into view, and the trio spread their blanket over the grass, Ledger prayed the feeling would pass. Her friends seemed nervous too, but in a giddy way. She placed a clammy hand over her quickening heartbeat—it wouldn’t steady. Her vision began to narrow. Guiltily abandoning her ‘babysitter’ role, she simply couldn’t remain.

“Hey guys…I think I’m going to call an Uber, I’m sorry…”

“Are you okay?” they answered, concerned.

“Yeah, I just want to go home. I want you guys to have fun!”

And with that, Ledger’s plans for a fun night were dashed with the arrival of the Uber, an awkward goodbye, and growing unease.

“You know, honestly, I had such great experiences on [magic mushrooms], such a positive connection to this earth and life that I never gave up an opportunity,” reflected Ledger, a 31-year-old Omaha native working in healthcare. “In fact, I ended up moving out of Nebraska with my significant other, and we actually bought half an ounce of magic mushrooms and I ended up pretty semi-regularly taking them.”

When Ledger visited her hometown for her aunt’s funeral in 2018 and found out two of her best friends had yet to indulge, she thought it would serve as the perfect distraction from the somber tone of her visit. Her friends, after she left, she’s told, had a lovely time. However, despite the vibrant interior and colorful lights of her driver’s vehicle, Ledger was barreling toward a dark tunnel.

“I knew my friends knew I was distressed, but I also knew I just needed to get to a safe place where I could lay down,” she continued. “I didn’t know what was to come…but I knew I needed to get out of there. I needed to get home.”

The loud music and strobing ambiance of the car only amplified her sense of dread and panic. She called her brother on the way, taking deep breaths as he strained to listen to her panicked voice: “I’m having a very bad time. I’m heading to our parents’ house. I’m having a very bad time.”

Upon arriving at her parents’, she called her significant other, who urged her to induce vomiting. But it was too late; the psilocybin had already metabolized. The intrusive thoughts were here to stay.

“If you can imagine every uncertainty that you have in your life rearing, it’s all in the room with you, no matter where you look or sit, just looking at you and begging for an answer…and it just seemed I gave in, and I said I didn’t have an answer,” she said. “Every insecurity, every unaddressed, unsettling thought you’ve had about your life. Being in your mid-20s, it’s easy to confront them. But having them all in the same room with you, almost having their own face, was just so overwhelming…

“I remember going into my brother’s room and just pulling his comforter over me and just laying in the fetal position, trying to block them out of my head.”

They didn’t relent. Childhood traumas, the morbidity of her aunt’s death, sharp claws of regret—over her career choice, her living situation, her bad habits, friendships lost—tightened their grip on her psyche. She lay in a ball, begging for it to end; she began to believe it never would.

“I’m going to always have this perspective. I’m stuck here with this perspective and this is just how I’m going to view the world […] I don’t want to create a life off of this basis, it hurts too much,” she recalled thinking. “I just thought, ‘Death sounds so sweet.’”

Thankfully, her brother finally arrived home. He held her, told her he loved her, and offered her sage advice.

“He said one thing that really stuck out to me that I remember pivoting my mind, as like, a foothold out of darkness,” Ledger said. “He said, ‘Marie, I’ve been there before, and I can promise you it’s temporary. I can promise you the feelings you are feeling right now you will not feel them forever. You just have to give it time.’”

Eventually, his words became truth, and the psychoactive effects dwindled away. But they left scars on their way out. Ledger fell into a deep depression for months afterwards in what she describes as the “darkest time of [her] life.”

“And that’s when I had to start rebuilding my perspective of myself, and it was not easy,” she conceded. “I always prided myself on being introspective before, but this [experience] just tore down myself. My ego, my pride, my perception of myself and other people, just points I hadn’t even deeply considered.”

Despite all this, Ledger has come to embrace the transformative, however torturous, lessons learned that night. When asked if she regrets the experience, she answered:

“Absolutely not. I don’t regret it in the fact that I feel that I have met my psychological rock bottom. I’ve seen myself reach lows I didn’t know were possible, and I put in the work to get to where I am now,” she explained. “It’s given me more self confidence. How do you get to know yourself unless you’ve been through trials and tribulations? It gave me a new perspective that I’m very thankful for. Going through it, I wanted to die. But looking back, I know myself so much better for going through it.”

Ledger demurred that she was likely overdue for a “bad trip,” given the frequency and recklessness of her usage. She’s even ‘tripped’ a few times since, though she’s far more mindful of the amount ingested, the variety of the fungus, and especially, the capabilities of the molecule inside.

“I would never approach the drug in the same way,” Ledger affirmed. “A healthy, cautious amount of respect for its power is key to fully enjoying and benefiting from it.”

Development

“There’re two entirely different kinds of phenomena. One is called ‘challenging experiences.’ Say you’re in your psychedelic trip, and you are trapped in a graveyard that you can’t get out of or whatever. People with support get through those, and they often find them beneficial,” Lukas said of so-called “bad trips.”

“But there are these other experiences, where when you come back, things are not right […] a small amount of them, but the phenomenon is known. We’d like to know more, which is why we need more research,” she added.

Isolation and unknown dosages are two of the strongest predictors of such experiences. In a clinical setting, they’re virtually unheard of.

As for the future of psychedelic-assisted therapy in Nebraska, Lukas is already looking ahead. She’s currently raising local funds to launch a safety study on exploring psilocybin’s impact on alcoholism, noting the high number of young people who die of alcohol-related disease here relative to the East Coast.

“They’re not candy, they’re not magic—they’re some of the most powerful substances we have,” she concluded, reiterating the untold benefits of harnessing, rather than abusing or neglecting, this power.

“The therapeutic effect will be worth it.”

For more information, visit palliadelic.org.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2024 issue of Omaha Magazine. To subscribe, click here.