Gary Kropf, 62, spent the entire evening reading Wine Spectator magazine cover to cover.

On the toilet.

“It was a busy day,” Kropf recalls. A powder laxative mixed in 64 ounces of Gatorade helped clear his gastrointestinal tract for inspection.

He doesn’t regret a single minute. It wasn’t a fun day, but it was easier to drink the dreaded “colonoscopy cocktail” than die.

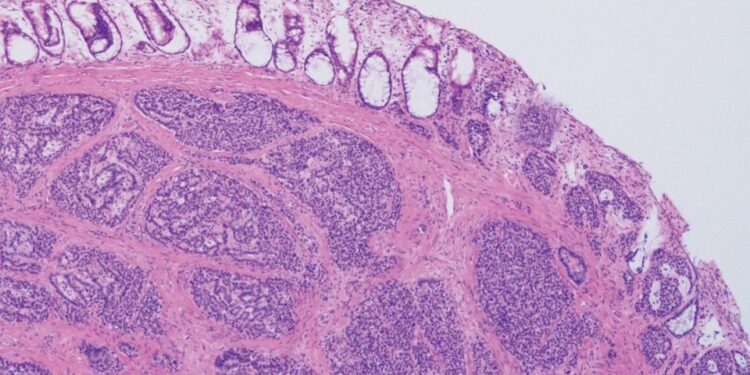

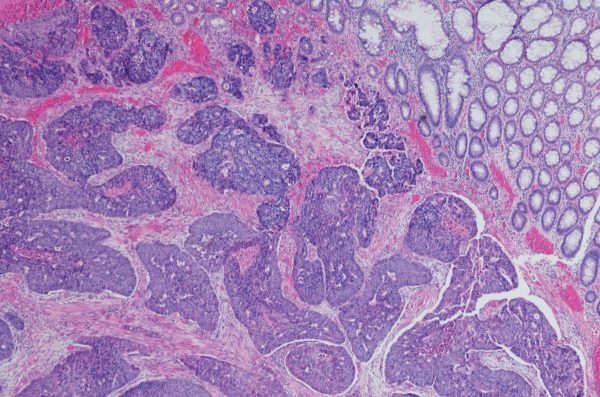

What his doctor discovered after Kropf had the procedure were two polyps, or growths in the intestine, which could develop into cancer. Kropf didn’t panic since he went through a procedure to remove polyps five years before. This time, however, one polyp flattened out and couldn’t be removed. His biopsy tests came back as slightly abnormal. Kropf sought a specialist.

“Gary, I’ve seen a lot of these. I bet it will turn into cancer,” colon and rectal surgeon Sean Langenfeld informed him.

Kropf understood the impact of those words more than most. His first wife died of uterine cancer. He had seen firsthand how fast cancer could take a life.

Unfortunately, Langenfeld was correct. Tests came back positive for cancer.

“I’m not a betting man. I don’t like the odds,” Kropf says.

In fact, according to the American Cancer Society, colon cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death in men and women. However, almost 59 percent of those 50 and older—the recommended age for testing—do not get tested.

Most, Langenfeld believes, do not get the colonoscopy procedure because it is embarrassing.

Geraldine Russmann, 80, had a laparoscopic colon resection after discovering cancer last year. Russmann, also a breast cancer survivor, has trouble talking people into having a colonoscopy because they think cancer won’t ever happen to them.

“It’s a day out of your life that will save your life,”rshe says.

Preventive screening seems to be key to a longer life since many times there are no symptoms, as was the case with both Kropf and Russmann.

Excluding family and personal history, a colonoscopy is recommended every 10 years to identify polyps and cancers in patients before they have symptoms or the cancer spreads.

Kropf is remarried, and he is urging his second wife to get checked (she can’t stomach the idea of going through the pre-bowel prep experience).

But Langenfeld says the chalky cocktail is now “less miserable and tastes better.” The day of the procedure, the patient is sedated. The surgeon uses a colonscope with a tiny camera at the tip to see a visual of the colon and removes any polyps if necessary. It typically takes about 30 minutes.

“It can change your life to not wearing a bag or getting really sick,” Kropf adds.

Kropf had much anxiety in those dark days, but felt confident in Langenfeld’s abilities. Langenfeld, a five-year University of Nebraska Medicine veteran, has seen many of these cases. He knows if a polyp gets out of hand, a person can die. He has seen these red or pink masses become so huge they “block the road.” The biggest was the size of a football, while others were like softballs.

As of December, Kropf’s blood work came back favorable.

How did he celebrate?

“I had a nice glass of wine,” Kropf says.

Visit cancer.org for more infomation.

This article was printed in the March/April 2017 edition of 60 Plus.