With his continental charm and killer cooking skills, Erwin Siegler gained entry to the international culinary scene and its disparate cultures and cuisines. The journey of this former Omaha chef began in his native Germany, where he earned his chops in the lean post-World War II period.

He was recruited to America in the early-1960s by the Radisson hotel family. He started his own catering company in 1976 and he gained U.S. citizenship in 1980. His business enjoyed a three-decade run. Siegler became a fixture on the local food scene. He was president of the Omaha Restaurant Association, a charter member of the Omaha International Wine and Food Society, and a cooking instructor at Boys Town and Metropolitan Community College. In 2000, he was elected to the Omaha Hospitality Hall of Fame.

Retired Omaha physician Michael Dunn knew him from IWFS. “He put on many five-course meals, both for the society and individual members, and they were always outstanding,” Dunn said. “He’s a very creative, personable guy. Very knowledgeable about matching food and wine. He exposed to me things I never had before.”

Another friend, Phillips Manufacturing CEO George Kubak, recalled sumptuous feasts Siegler prepared for the plant’s employees. “He made the best Thanksgiving meal you’ve ever had,” Kubak said. If lucky enough to get invited to Siegler’s home, as Kubak was, it meant eating “out of this world schnitzel and spaetzle.” Life in the food industry can be difficult, but he found his lane in the field.

“I never complained,” Siegler said. "I had it good all the way.”

His passion and ambition took him far from his rural origins in the small Bavarian town of Lohr am Main. He was the seventh of 10 siblings in a Catholic family. His father was a farmer and contractor. Their hometown went largely untouched by the war. Per European custom, Siegler faced a choice upon finishing high school of continuing his schooling or entering a trade. He opted for the culinary field because an older cousin he admired was a cook.

He landed a break when the Bavarian governor, a chef by training, took an interest in him. The governor owned a business making specialty food items (goose liver pates, oxtail soup) for hotels and he got Siegler on as an apprentice under its master chef.

Siegler credited the governor for the chance to learn his vocation. “He just loved the way I was interested in it,” Siegler said. “He called me ‘my son.’ He helped me all the way.”

Upon graduating with special honors, the apt pupil got placed at a first-class hotel in Interlaken, Switzerland, courtesy of his mentor. Siegler said, “Going there was the best choice I made in my life.”

Another mentor advised he learn English. He did, and it led to a gig in northern England, where he learned under an Italian chef. A new opportunity brought him back to Switzerland, this time to the Kulm Hotel at St. Moritz. Between resort seasons, he worked on the Rotterdam and New Amsterdam Holland American cruise lines to New York, the Caribbean, and Cuba.

Wherever he went, his personality paved the way. “I am an easy guy to befriend,” Siegler said. “I make friends right away.” Being a people person, he said, “Is how I got through life.”

He was driven enough to earn certifications in all the stations—from sauces to soups—at the Kulm, whose head chef recommended Siegler to the Onassis family. They owned a hotel chain in Greece, and Siegler helped open two new properties. At the first, on the island of Corfu, he improvised with fresh, local ingredients (lamb, lobsters, figs, and fennel) when its power failed.

Then America came calling. Radisson wanted him so badly the hotelier arranged with the Swiss consul in Zurich for the Sieglers to receive expedited visas.

He'd worked three years in Minneapolis when the company acquired the Blackstone in Omaha, and Siegler was dispatched to turn around its food operations.

“It was a challenge and I like challenges,” Siegler said. “I especially like it when you see an improvement. It makes you feel good.”

He succeeded on the food side, but it wasn’t enough to save the hotel. Seeing the writing on the wall, he followed its former manager to the Ramada Inn, where he routinely achieved the lowest food costs across the company’s national chain.

The chef soon felt established enough to start his own business, Siegler’s Catering. He didn’t want for clients. “I had so many people calling me.” He catered major events for Creighton Prep and Duchesne Academy. “You make your money from the big parties.”

He ran the food operation in the Mutual of Omaha Dome cafe.

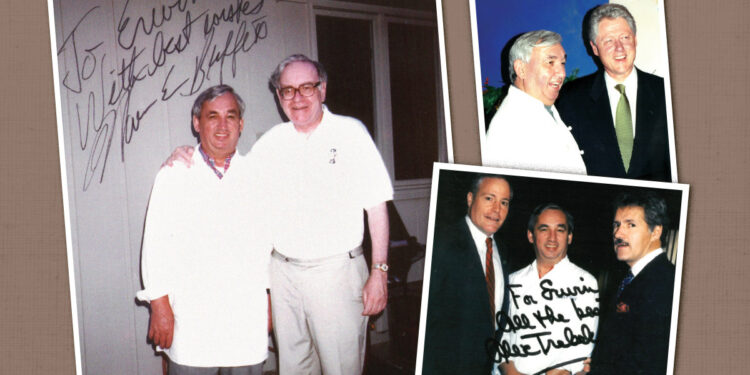

“Then I got all the politicians,” said Siegler. “The first was President [Gerald] Ford. The Republicans hired me to do the party. Then came George Bush I. A big GOP donor hosted it. Then came Bill Clinton and after him, Hillary. Both Clinton parties were at the home of a big Democratic Party donor.”

Siegler led culinary-spiced tours of Europe for Omaha business execs with gourmand tastes.

Back home, churning out volumes of meals got to be too much.

“It was hard, hard, hard work. I had 16-17-18 hour days. I had some help, but the cooking I did more or less all myself.”

He never intended making America his permanent home, but it’s where he made his greatest mark pleasing people.

“We [he and wife Edith] wanted to go back home after five years and we did go home,” he said, “but nothing was right for me after being away. I wasn’t satisfied enough. I’m glad we came back to the states. The opportunity was here and I could make my own business.”

He firmly believes the American dream is intact.

“If you want to work here, you still can make money, and I was a hard worker,” Siegler said. “My wife always said, ‘We won’t get rich, but we’ll have a good living.’ That’s what we did.”

Editor’s note: Siegler died on Sept. 11, 2020, following a brief battle with cancer.

This article first appeared in the 60 Plus section of the November/December 2020 issue of Omaha Magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.