The community was in a panic. People stayed inside their homes. They avoided movies, camping, vacations and swimming. Anywhere that polio might lurk.

And when polio did strike the family…

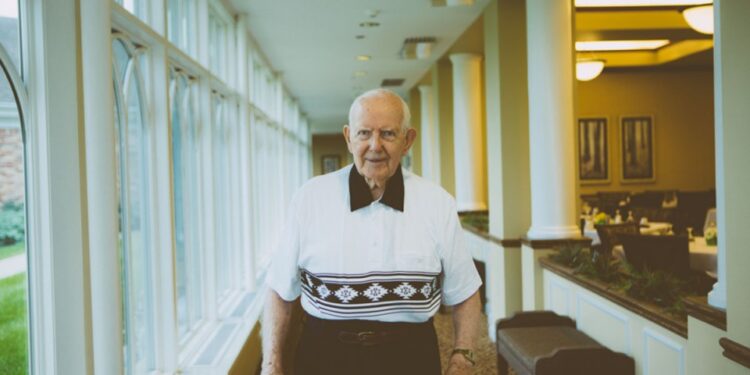

…“I was torn apart by the anxieties and sadness on the faces of the parents,” says the retired Omaha pediatrician. “You could see anguish drop over their eyes. With the few tools available at that time to combat polio, I could provide very little solace for their relief.”

It was a tough summer for pediatricians like Oberst. “1952 was one nightmare after another. We were working 26 out of 24 hours a day. We got maybe a few hours of sleep.”

“There were so many sick children, it made your heart sick.”

Doctors hoped that the worst outcome would be a limp leg. But bulbar polio could kill or completely paralyze a child, leaving the child in an iron lung.

The memory of 1952 stayed with Oberst. Years later, he attended a dinner featuring Dr. Albert Sabin, the developer of the oral live virus polio vaccine. Oberst was shaken when he saw an iron lung on display. The sight sparked flashbacks to 1952.

“My heart started pounding. Chills were going up and down my spine. I could hear the clanking of the lung. I saw a child die All I could remember were those horrible days,” he says.

Memories of the more than 360 children treated at Omaha’s Children’s Memorial Hospital in summer 1952 flooded back. At least 14 were in iron lungs.Thirteen died that summer.

It was the worst outbreak in Nebraska history. The disease’s original name was Infantile Paralysis, because it seemed to primarily target young children. But some victims were adults.

Unlike many of the other younger doctors at Children’s Memorial Hospital at the time, Oberst had experienced treating polio while serving in Japan in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. When he joined Omaha Children’s Clinic in 1951, he and some of the older pediatricians were the only doctors who had seen a case of polio in their lifetime.

In 1947, Oberst became the first and only resident at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, now UNMC. In March 1948, Children’s Memorial Hospital opened on what is now the UNMC campus at 42nd and Dewey streets

The sighs of relief heard from pediatricians after their patients survived with few problems stopped in the early 1980s when post polio syndrome gradually emerged. Many of the polio survivors who had gone on to normal lives suddenly found their muscles were weak.

Darrel Sudduth of Plattsmouth is just starting to notice signs of post-polio syndrome more than 60 years after his recovery. He was 12 years old when diagnosed with polio during the 1952 epidemic.

“I don’t think my parents had ever heard of the disease,” says Sudduth, who is a member of the Nebraska Polio Survivors Association.

During two weeks of isolation in Children‘s Hospital, his parents were not allowed to see Sudduth. Until now, the only residual effects had been a bad back and one leg shorter than the other.

Oberst, 91, is known for several “firsts” in pediatric medicine during his long career:

Doctors from around the nation referred patients with Attention Deficit Disorder With or Without Hyperactivity to Oberst, who was a pioneer in treating the condition then referred to as Minimal Cerebral Dysfunction. “But that name scared parents to death,” he remembers. He treated 3,000 children with ADHD.

Oberst developed The Omaha STAAR Project to help parents, doctors and teachers understand children with learning disabilities.

While a resident, he pioneered the use of exchange transfusion for Rh-positive babies and their Rh-negative mothers. The transfusion was necessary to keep babies from being vulnerable to brain damage, deafness or yellow jaundice.

With all of his accomplishments, Oberst not surprisingly believes that pediatrics is the most satisfying of all specialties. However, the three sons and three grandsons of Oberst and his wife, Mary, who died in 2011, chose careers outside medicine. The family includes his famous grandson, singer-songwriter Conor Oberst of Bright Eyes.

Dr. Oberst has written seven books; some are medical books. The American Academy of Pediatrics presents an award in his name each year.

During his 40 years as a pediatrician, he treated thousands of children. But no memory is as heart-wrenching as the 1952 polio epidemic.

After the Salk vaccine was introduced in 1954, there were fewer cases. By 1979, there were no more cases in the United States. Polio appeared to be eradicated. But in some foreign countries where children are not vaccinated, it is resurging

“Some stupid people say their child shouldn’t be vaccinated,” he says. “They put that child at risk.”