Sarah and George Joslyn came to Omaha for the same reasons people do today—job opportunities. Originally from Vermont, they arrived here in 1880. George earned $18 per week as manager of the Western Newspaper Union (WNU); as a new century dawned, he was president of a burgeoning conglomerate. The couple moved comfortably among Omaha’s wealthy and powerful elite and made plans for their dream home, which would become the crown jewel of Omaha’s Gold Coast neighborhood.

The Joslyns’ fabled life ended long ago, and no descendants live in Omaha. Still, their positive influence in our community can be felt by thousands of Omahans: by the artists who found inspiration at Joslyn Art Museum, the children who found homes through the Child Saving Institute, the students who reached their goals at UNO, the fellow church members at First Unitarian, and the strays who found some tender loving care at the Nebraska Humane Society; women and children in dire circumstances, soldiers away from home, and people old and alone—in fact, all of us have inherited the legacy of the Joslyns’ success, ideals, and vision.

“The Joslyns were a power couple,” says Daniel Kiper. “Both had intellect, drive, and ability, and they shared common goals.” Kiper probably knows the Joslyns as well as anyone can who’s never met them. After serving as a docent and board member for the Friends of Joslyn Castle, the Joslyns’ majestic home, he researched and wrote The Joslyns of Lynhurst. “I visited Joslyn Art Museum often as a child,” he says. “I felt I owed a debt to Sarah, who allowed me to see beyond the world I lived in.”

Omaha proved to be the right place for the Joslyns, and they’d arrived just when the nascent city was ripe for opportunities. Ambitious, canny, and charming, George expanded and diversified WNU’s niche in newspapers and added properties, investments, and other ventures to his hand. Julie Reilly, executive director of Joslyn Castle Trust, describes George as “the Ted Turner of his day.” In 1893, he purchased a five-and-a-half-acre farm at 39th and Davenport streets. Landscaping began at once, but it would be 10 years before the house was finished. And when it was, the public gave it the name it has been known by ever since: Joslyn Castle.

“The Castle,” house and grounds, was lavished with luxury and reflected the Joslyns’ tastes: trees and shrubs, (many exotic, watered by underground pipes), a swimming pond, a conservatory for their orchid collection, stables for thoroughbred horses, a carriage house, and other outbuildings. The 34-room house, designed by John McDonald in Scottish Baronial Style, cost $250,000 to build, plus $50,000 in furnishings. The house had its own conservatory, music room, gym, bowling alley, even a lavatory for their Saint Bernards’ muddy feet. Sarah’s favorite room was the morning room, with personal photographs on light blue walls and a unique flower-display window.

Kiper says they certainly enjoyed themselves, indulging their interests in art and music, animals, travel, and entertaining. But they took the idea of noblesse oblige seriously: They gave to the community in both money and deed. Kiper cites numerous examples in his book, including their support of the Old People’s Home. Learning that the founder was near death and despaired of reaching her goal of new quarters, the Joslyns visited her with a property deed and $10,000. Once the new home was in operation, Sarah could be found sweeping the floors.

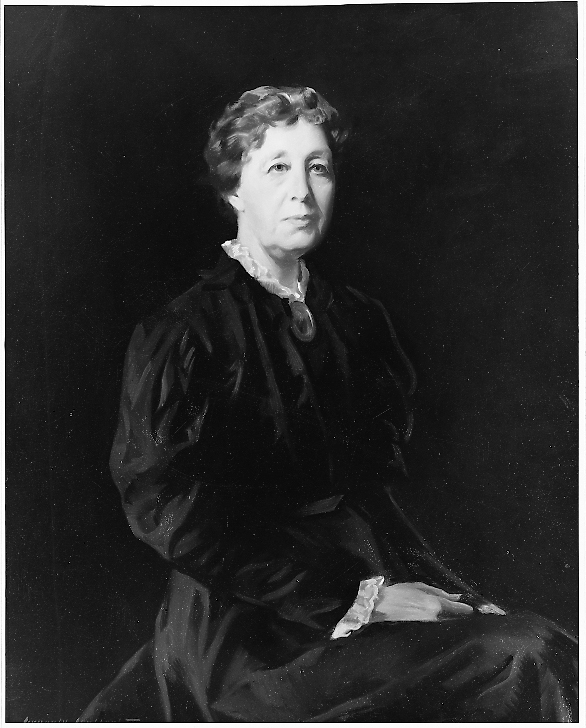

In Joslyn Art Museum: A Building History, former director Graham Beal includes a history of the Joslyns. “They were an extraordinary couple…who contributed so much to the early social, artistic, and intellectual life of Omaha. In my mind…[I picture Sarah as] a highly intelligent, unpretentious yet sensitive woman.” Beal describes Sarah’s charitable involvement in projects such as opening her home for fundraisers, serving on boards and commissions, and a variety of efforts during World War I. Always there was that combination of public roles and personal response; she did what needed to be done.

Wanda Gottschalk, chief development officer of Child Saving Institute, describes her image of Sarah as “a very, very bright woman who was frustrated by lack of opportunities for women.” In addition to donating $25,000 for a new building, Sarah served on CSI’s board, rocked babies as a member of the Nursery Committee, and invited the children to picnics on her home’s park-like grounds.

“It may have been one of those occasions where she met Violet,” Gottschalk says. In 1897, five-year-old Violet came to live with the Joslyns; she would become their cherished daughter and the princess of Joslyn Castle. In 1913, seven months after the horrific Easter Sunday tornado devastated Joslyn Castle, Violet was married in the renovated, flower-filled rooms.

After George’s death in 1916, Sarah’s focus became a memorial that would honor her husband, represent his values, and provide a permanent home for the arts. She held fast to his idea that, as their wealth had derived from Omaha, it should, in some form, be returned to the city for the benefit of its citizens. Jack Becker, Joslyn Art Museum’s executive director and CEO, notes, “Sarah Joslyn built the museum as a memorial to her husband and gift to the people of Omaha. She was very clear from the beginning that her wish was for the museum to be enjoyed by as many people as possible, for as long as possible. Sarah lived to see the museum’s first decade, during which time an admission fee was never charged. The policy of free admission continued for another 25 years after her death in 1940, and we are proud to return to it this year.” Free general admission was reinstated in May 2013.

On opening day, Nov. 29, 1931, Sarah gave us not only the Joslyn Art Museum but its future in saying: “If there is any good in it, let it go on and on.”