Craig Hughes graduated from college with what he calls a “design as decoration” attitude and went straight into the world of advertising.

As for the notion of conducting classic “field work,” he considered that a realm reserved for social scientists, anthropologists and others in the more “sciencey” of endeavors.

But Hughes, now the president of Nebraska’s chapter of AIGA, the professional association for designers, found himself in a hotel bar at an industry conference chatting it up with some of the legends in his field as the 2009 BP oil disaster was unfolding.

“What they need to do,” Hughes recalls one of the designers saying in gesturing to a TV as BP news reports flashed across the screen, “is get all of the engineers out of there and get in the designers to brainstorm.”

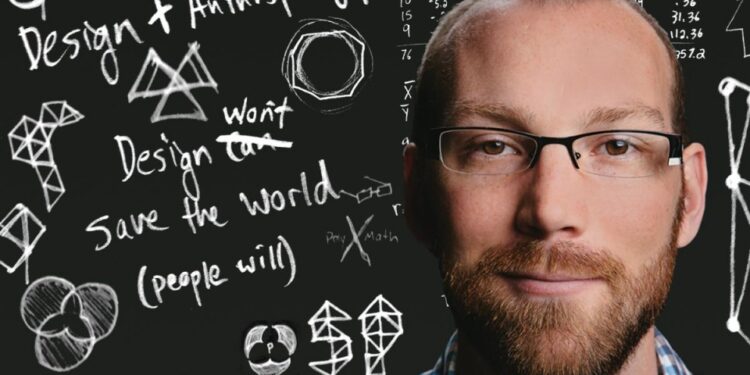

“But that’s not what design does,” Hughes remembers thinking. “The idea that you kind of have to fight this battle of disciplinarianism, that ‘get rid of all of these other people and design will save the world’ approach. It doesn’t work.”

The incident was just one of the sparks that fired an evolution in his thinking. Hughes soon began exploring other—much more diverse and disparate—ways of applying his design training, ones that have increasingly found him in the arena of doing field work alongside sociologists, architects, lawyers, anthropologists, and others.

Hughes is now pursuing a master’s degree in sociology through the University of Nebraska-Omaha. This fall he will partner with community organizations in a decidedly “un-designey” effort to seek solutions in urban planning initiatives that revolve around general themes of social advocacy.

In December 2012, he left his job as an associate creative director and opened Studio Polymath, a design firm that works with experts in a wide array of fields to solve interesting or persistent problems.

And that’s how Hughes found himself in a nursing home with a team of interdisciplinary experts, asking a 93-year-old retired cook what advice he would give to himself at age 43.

“Don’t live too long,” Hughes recalls the man saying.

Too long, the man told Hughes, came the very moment he walked through the nursing home’s doors and, in doing so, lost his identity.

Back in Omaha, Hughes and his cadre of thinkers spun ideas to address some of the problems revealed in their interviews.

“What are some things that we can be doing,” Hughes asks, “so we’re not just putting people in a box where they collapse spiritually, mentally, physically, emotionally?”

The next step for the project is to test a pilot program that would give nursing home residents such new and more vital experiences as the chance to work with their hands or to teach as masters or amateur historians in their respective fields.

“A brain in use is a powerful thing,” Hughes adds.

And the more brains the better.

“Humans and our ancestors have been solving problems for millions of years and no single discipline has all the answers,” he says. “All of those things together are what will address those big, nasty problems that graphic design alone can’t solve.”