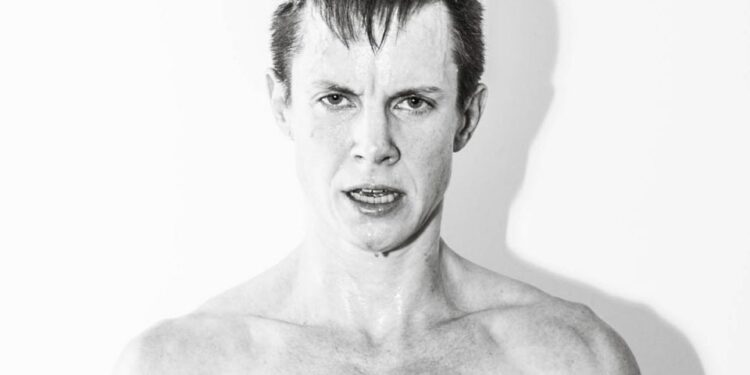

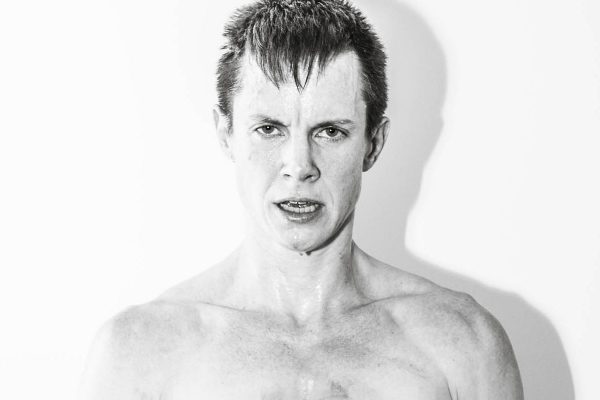

Editor’s note: Cassils is a gender non-conforming trans-masculine visual artist. Cassils uses plural gender-neutral pronouns (they, them, their) and asks that journalists do likewise when referring to them. This plurality reflects through language the position Cassils occupies as an artist. For more about gender non-conforming issues, go to: glad.org/reference/transgender

Powerful art does not need to be explained, though for the uninitiated, sometimes it helps.

Canadian-born, Los Angeles-based multimedia artist Cassils thrives on the power of art. The artist (who prefers to be referred to in plural, gender-neutral pronouns) launched their latest exhibit, Cassils: The Phantom Revenant—now on display at the Bemis Center— Feb. 2 with a thrilling live performance called Becoming An Image.

Cassils’ performance involved the transgender, body-building artist attacking a 2,000-pound block of clay using only their body, in complete darkness, with the occasional flash of a camera that illuminated both artist and object, burning the images into viewers retinas.

It was a blend of performance, photography, and sculpture. “I use all parts of my body—my fists, my knees, my elbows,” Cassils says. “I beat this clay to the best of my ability, blind, until I’m basically compromising my ability to hit it properly.”

At the performance, the only sounds were those of Cassils’ labored breathing, as the artist kicked, punched, and even jumped on the earthy clay, accompanied by the click of the camera as the photographer blindly tried to capture the “full-blown attack.”

Becoming An Image was originally conceived of and executed for ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, the oldest existing LGBT organization in the United States, which also happens to house one of the largest repositories of LGBT materials in the world.

“I was asked to make a piece in relationship to the missing gender-queer and trans representation in that archive, because like many archives in museums, it’s filled with the work of, in this case, dead, gay white guys. So rather than making an artwork that spoke to the one or two subjectivities that perhaps matched this description in the archives, I decided to make a piece about the troubling mechanisms of what makes it into the historical canon and what doesn’t.”

Cassils’ Powers That Be installation—on display through April 29—presents a six-channel video that is a simulation of violence, a staged fight that could be taking place between two, three, four, or five people. But in this fight, Cassils plays the role of both victim and perpetrator. “If you have two people doing stage combat, it looks really realistic, but if you take one person out, and the other person’s doing it well, it really looks as if they’re fighting a ghost, or a force.”

Cassils says “Any work is about responding to the socio-political circumstances that we’re living in … Art doesn’t change things like laws do, but it generates discussion.”

This article was printed in the March/April 2017 edition of Encounter.