The morning of the funeral, I woke early to write my identical twin brother’s eulogy. It began: “On the cover of a notebook, Connor spelled out his definition of art in boldface type: ‘Art is not communication. It is dialogue.’”

Robert Connor Meigs suffered severe brain trauma in a car accident three blocks from our childhood home on Dec. 20, 2004, in Omaha. I was driving and regained consciousness in a hospital bed. He died four days later.

The principal from our elementary school, Mrs. Krause, read Connor’s eulogy on behalf of my family during the service. I sat in the front church pew with my older brother, sister, and parents.

As Mrs. Krause spoke, I remembered saying goodbye to Connor in the hospital on Christmas Eve. Looking at his face, it was like looking into a mirror, but my eyes were closed. Tubes protruded from his scalp. IVs chained his limp body to beeping machines. A miniature Christmas tree sat in the corner, turned off. His lungs still heaved via breathing machine. But because of a blood clot, his brain hadn’t received any oxygen for hours. He seemed to be sleeping when I walked away.

She continued reading: “Connor was taken from us just as he was finding his artistic voice. His dialogue had just begun to take shape. He died too young. But his voice lives on. He lives in our memories.”

Shadows fill my memory of the accident. I remember the Jeep sliding on an icy road. I remember arguing with my brother, then darkness.

A police report explained the events: I lost control on black ice. We spun onto the opposite side of the road. The oncoming truck couldn’t stop. It plowed into Connor’s door, slamming our Jeep into a parked van. The following day, I regained consciousness. Connor did not.

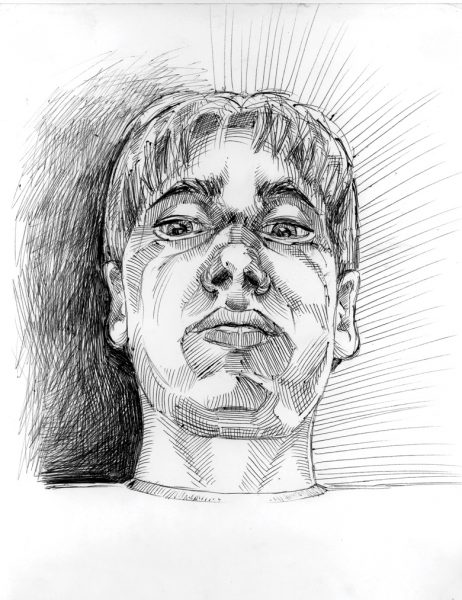

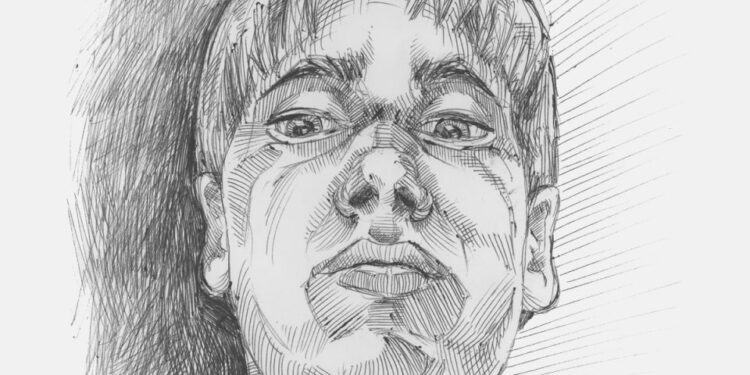

His eulogy continued: “The anecdotes from Connor’s life trail back 19 years. We all have them, and each of ours is different. The most consistent anecdote remembered by his close friends and family is his dedication to art.”

Mrs. Krause spoke about Connor’s unexpected arrival for Thanksgiving break: He pulled into the driveway, barged into the house with a stack of canvases, disappeared again, and returned with more artwork. My mother, a local artist, promised to help him organize his first exhibit at the ArtLoft Gallery at Florence Mill after he graduated. He died halfway through his sophomore year at the University of Kansas.

While Mrs. Krause spoke, I remembered Connor’s phone calls from the School of Fine Arts at KU or his summer job at a bronze foundry in Prescott, Arizona. Like most siblings, we argued often. Connor especially liked to argue about art. He said things like, “Art is not communication,” then welded a 6-foot tall, foldable, portable communication tower out of iron.

r r

r

I thought he’d spent too much time in the studio, too much time with paint thinner, too much time distinguishing squares from rectangles.

In the eulogy, I explained my brother’s concept of art, as he sat atop his communication tower during his final sculpture critique: “Through the communication tower, Connor was trying to articulate the unique power of an artist as he wobbled to and fro in the center of the class’ attention.”

By itself, any expression can be a form of communication. But not all communication is art. When communication is interpreted, when a viewer comprehends the message, a two-way bridge is formed, a dialogue.

Mrs. Krause finished reading. Mom had arranged an art exhibit in the church’s fellowship hall to follow his service. I stood by one of the entrances and thanked the well-wishers who followed.

A tiny woman approached. She said her name was Mrs. Maher, our kindergarten teacher. Two misshapen, miniature clay books dangled from dental floss necklaces around her neck. She cupped the ornaments and held them forward. We had given her the necklaces in kindergarten. “Connor was the shy one,” she recalled. At the time we had given her the gifts, Connor had hidden behind me.

After the funeral, I went home, closed the door to my bedroom, and I cried. I had driven my twin brother, and all his gifts, to the grave.

But life, like art, does not fit clear-cut definitions. My brother’s voice lives on in his artwork. His memory will live on through helping other young artists. My mother, Linda Meigs, initiated the Connor Meigs Art Award in the summer of 2007. The goal was to help young artists achieve what Connor could not—the beginning of a career.

A posthumous art exhibit, titled Connor Meigs: Retrospective Dialogue, ran during the summers of 2005 and 2006 at the Florence Mill’s ArtLoft Gallery. In October, his show moved to the Beatrice Public Library in Beatrice, Nebraska.

Now, his artwork rests in family members’ homes.

Postscript: The first recipient of the Connor Meigs Art Award exhibited in the summer of 2007. Seven artists have received the award: Nicholas Shindell (2007), Sariah Ha (2008), Stephanie Olesh (2009), Matthew Farley (2010), Woohyun Shim, (2011), Christine Fredendall (2012), Kathy Irwin (2013). The Connor Meigs Art Award was temporarily postponed in 2014 as my father, John Meigs, fought a terminal cancer diagnosis. But the award will continue. The 2019 recipient is Holly Tharnish, a recent graduate from the University of Nebraska-Omaha.

The Connor Meigs Art Award provides an honorarium of $1,000, studio visits to the working spaces of Omaha artists, and a solo exhibition with artist reception. The Fort Omaha campus of Metropolitan Community College sponsors lodging for out-of-town recipients.

Connor’s legacy, however, does not end with art. His driver’s license noted that he was an organ donor. Doctors removed his liver, kidneys, heart valves, corneas, and some leg bone for the ultimate Christmas gifts to complete strangers.

I met one of those strangers during the summer of 2005. A Norfolk, Nebraska, resident named Maggie Steele visited Connor’s exhibition at the Florence Mill to thank our family. A genetic disorder—alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency—had destroyed her liver, she explained.

She received his liver on Christmas Day in 2004.

How to apply for the Connor Meigs Award

The award is restricted to recent graduates—or those soon to graduate—with a Bachelor of Fine Art degree. Applicants should submit a resume, artist statement, and 10 images by mail to the Florence Mill ArtLoft (9102 N. 30th St., Omaha, NE 68112) or by email to [email protected]. The application deadline is Oct. 1, 2019, for a 2020 exhibit.

Visit connormeigsartaward.com for more information. A version of this essay was originally published in the Columbia Missourian’s Vox Magazine on March 15, 2007.

This article was printed in the January/February 2019 edition of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.