You may not know of Mary Kimball, but if you’re an aficionado of historic Omaha, you know her son, Thomas Kimball, very well. The architect behind St. Cecelia Cathedral, the Burlington Station, and the famed structures of the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition, among so many others in Omaha, was a major figure in America’s architectural community for several decades before and after the turn of the last century.

While Kimball is most known for commercial and civic structures, he also designed homes for well-to-do Omaha residents. Many of those have fallen victim to Omaha’s oft-blind march of progress. A few remain. One, clearly built with loving attention to detail, still towers over St. Mary’s Avenue between 22nd and 23rd streets and is widely considered Kimball’s residential masterpiece.

In the successful 1996 application to place the home on the National Registry of Historic Places, the home Kimball built for his mother and sister is broadly categorized as Dutch Colonial. Among myriad other details, the exterior boasts five parapets on the masonry box structure that help create a dramatic verticality—a hallmark of Kimball’s work.

Inside, the 108-year-old house becomes more of a stylistic mash-up. Greek Revival details and clean, practical Arts and Crafts features (chosen mainly to foster ease-of-living for Kimball’s beloved mother and sister) are accented throughout with mahogany, quarter-sawn oak, and tiger maple woodwork.

Even though the house has long been in disrepair as a multi-unit apartment, the vast majority of original features remain. The bad news: The house is unoccupied and in need of a major renovation.

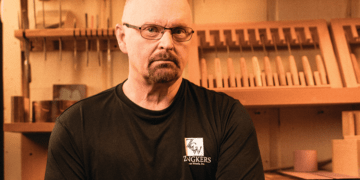

Thankfully, respected Omaha sculptor John Labja, who purchased the house six years ago, has been working to restore the home with great attention to Kimball’s original plan. A recent tour of the home suggests that Labja’s plan to move into the house in “one or two years” may be optimistic, but, whenever the completion date, the results should be stunning.

“This house is a masterpiece built by an amazing man out of love for his mother,” Labja says. “It deserves respect. Everything I’m doing here is intended to be very sensitive to the house and the vision.”

The house is a shamble of small projects in motion—restoration of exterior doors, returning long-carpeted floors to their original oak, stripping out everything in the kitchen or bathrooms that aren’t true to the period. Labja says he was thrilled to find many missing parts—tile, hinges, original fixtures—hidden away, forgotten, in basement recesses. In a year, or perhaps a few more, the Mary Kimball House should return to being one of Omaha’s most prized residential structures.

“As I do this work, I’m trying to let the house tell me what it wants,” Labja says. “The work has to be timeless, like the house itself. When this is finished, I hope we’ve shown it the respect and attention to detail a structure like this deserves.”