Warranted or not, creative ability and mental illness are viewed as traveling companions.

Since Lord Byron’s day, many literary critics have leaned into a poetic notion connecting “genius” and “madness.” Many artists have been posthumously diagnosed with everything from severe depression to schizophrenia based on hearsay and work product. Jack Kerouac, Vincent Van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, and others fall into an often-romanticized category of mentally ill geniuses.

In 2014, Harvard lecturer Shelley Carson said in James Kaufman’s The Shared Vulnerability Model of Creativity and Psychopathology: “In general, research indicates that creative people in arts-related professions endorse higher rates of positive schizotypy than non-arts professionals.” Perhaps. After all, art is about communicating to an audience a different perspective from the everyday. One is more likely to present a view of life outside the mainstream if they see the world in a way that others do not, and illness can certainly do that.

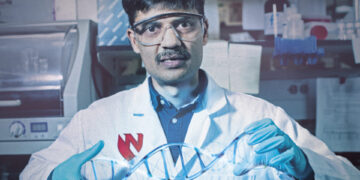

Zach Willard, 28, is an Omaha multimedia artist who goes by the handle ZWIAN (@Zach.W.is.a.Nerd). He works and experiments with video art, animated gif art, glitch art, mixed media, lenticular prints, woodburning, apparel, zines, and humor. He has also lived with mental illness for much of his life.

“I’m a definite jack-of-all-trades, master of none. Someday, I think it’d be nice to switch up and be a jack of a few trades and master of some, but I haven’t struck that balance yet,” Willard said. “Being a multimedia artist is like saying a person is a Renaissance man who knows how to work a computer.”

Ten years ago, Willard was diagnosed with manic depression, now more commonly referred to as bipolar disorder. In 2018, he was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and situational anxiety disorder.

“Generally, situations make me anxious,” Willard said. He has also suffered from undiagnosed chronic abdominal pain for much of his 20s, which became acute in the last three years.

In 2018, a scan showed a nodule on Willard’s adrenal gland, causing a cancer scare. Fortunately, he was was diagnosed quickly at the renowned Mayo Clinic and found that he was cancer-free.

“Unfortunately, the cause of my pain is still a bit of a mystery. I had to leave a job I really enjoyed working for—my parents’ business, Willard Auto Machine,” he said. “I did lots of physical labor, but due to my physician’s recommendation, I had to switch back to an office job.”

Willard uses art to distract from his illness, as well as to amuse himself and others. At a showing of his work at The HideAway art gallery in Benson, he used various images of digital glitches others might ignore. Willard captures them in screenshots or photographs them for examination.

Old videos others throw out are a goldmine of analog artifacts. He layers a variety of images culled from garage-sale VHS tapes with screen-capped digital glitches and images from his own life, such as animated pastiche set on a loop and projected on the wall or displayed on old television sets.

As much as his illness affects his life, Willard finds the romanticized connection between illness and creativity problematic.

“It’s bulls—. Everyone has the ability to ‘see the world in a novel and original way,’” he said. “It’s a matter of establishing an original perspective.”

Dr. Albert Rothenberg noted in a 2015 Psychology Today article, “Creativity and Mental Illness,” that the titular conditions are both nonnormative behaviors with similarities. Euphoria, mania, anxiety, and depression can be signs of mental illness as well as normative aspects of a healthy Janusian creative process.

Rothenberg said that mental illness can be a hindrance to creativity, and often the most productive artistic periods for afflicted artists happen when their mental illness is best controlled. As one example, Jackson Pollock suffered from alcoholism and bipolar disorder, but ushered in abstract expressionism during a time of great personal improvement in his condition.

“The idea that creative ability doesn’t already belong to everyone is unnecessarily exclusive in an effort to elevate people who are neurologically different rather than accepting that everyone is different in the first place,” Willard said. “To ‘literally see things that others cannot’ is psychosis. That is not a blessing nor an enhanced capacity, it’s an affliction that is harmful to look at through a rose-tinted lens.”

Willard said he does not believe that creativity or art are “Newtonian.”

“Every creative action in life doesn’t cause an equal or opposite reaction,” Willard said, adding that crediting mental illness for creativity “weaponizes” it. “Inspiration can certainly come from any form of hardship, but it isn’t a requirement. Weaponizing mental health can be a dangerous narrative. Even if I personally thought my worst mental health moments somehow influenced the best things I make, it wouldn’t make it a net positive or worth experiencing. An unexpected result or creation may be a silver lining to me having to deal with my health issues, but that doesn’t make it worth the clouds in the first place.”

Willard stressed the importance of keeping the number for The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on hand: 1-800-273-8255.

“People should program the number in their phones and share it,” he said. “Even if it seems like something you’ll never need yourself. It’s important for removing the stigma around reaching [out] for help.”

r

Visit zachwisanerd.com for more information.

rThis article was printed in the January/February 2020 edition of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.