Master craftsman and stringed instrument maker John Hargiss learned the luthier skills he plies at his North Omaha shop from his late father, Verl. In the hardscrabble DIY culture coming from their roots in the southern Missouri hills and river bottoms, people made things by hand.

“I think the lower on the food chain you are, the more creative you become. I think you have to,” Hargiss says.

He observed his late father fashion tables and ax handles with ancestral tools and convert station wagons into El Caminos with nothing more than a lawnmower blade and a glue pot. Father and son once forged a guitar from a tree they felled, cut, and shaped together.

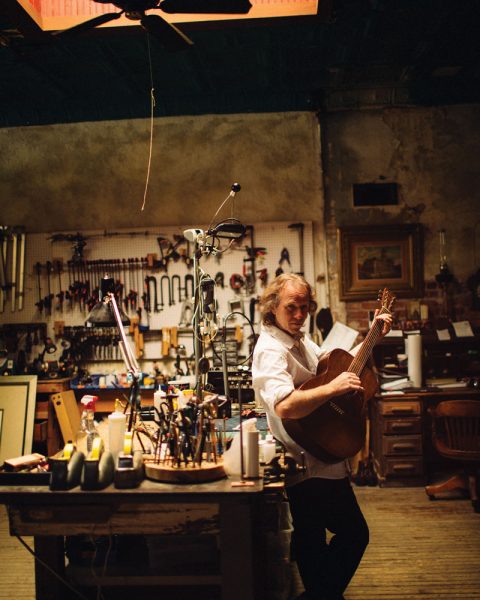

These days, the son’s hands are sure and nimble enough to earn him a tidy living at his own business, Hargiss Stringed Instruments. His shop is filled with precision tools—jigs, clamps—many of vintage variety.

Some specialized tools are similar to what dentists use. “I do almost the same thing—polish, grind, fill, recreate, redesign, restructure.”

Some specialized tools are similar to what dentists use. “I do almost the same thing—polish, grind, fill, recreate, redesign, restructure.”

Assorted wood, metal, and found objects are destined for repurposing.

“I have an incredible way of looking at something and going, ‘I can use that.’ Everything you see will be sold or used one way or the other.”

In addition to instrument-making, he’s a silversmith, leather-worker, and welder. A travel guitar he designed, the Minstrel, has sold to renowned artists, yet he still views himself an apprentice indebted to his father.

“He was a craftsman. Everything I know how to create probably came from him. Everything I watched him do, I thought, ‘My hands were designed to do exactly what he’s doing.’ On his tombstone I had put, ‘A man who lived life through his hands.'”

Hargiss also absorbed rich musical influences.

“(I was) constantly around what we don’t see in the Midwest—banjo players, violin players, ukulele players, dulcimer players. There are a lot of musicians in that part of the world down there. Bluegrass. Rockabilly. Folkabilly. That would be our entertainment in the evenings—music, family, friends. Neighbors would show up with instruments and start playing. Growing up, that was our recreation.”

He feels a deep kinship to that music, and his father had a hand in his musical development.

“My daddy was a good musician, and he taught me to play music when I was about 9. By 11, I was already playing in little country and bluegrass bands. I can play a mandolin, a guitar, a banjo, a ukulele, but I’m pretty much a guitar player. And I sing and write music.”

Hargiss once made his livelihood performing. “I like playing music so much. It’s dangerous business because it will completely overpower you. I knew I needed to make a living, raise my children, and have a life, so playing music became my hobby. I worked corporate jobs, but I kept being pulled back. It didn’t matter how hard I tried. I’d no more get the tie and suit off than I’d be out in the garage making something else.”

It turned into his business.

It turned into his business.

Hargiss directly traces what he does to his father.

“I watched him repair a guitar he bought me at a yard sale. The strings were probably three inches off the finger board. I remember my daddy taking a cup of hot coffee and pouring it in the joint of that neck and him wobbling that neck off, and the next I knew he’d restrung that guitar. I think that’s when I knew that’s what I’m going to do.”

The memory of them making a guitar is still clear.

“The first guitar I built, me and my daddy cut a walnut tree, chopped it up, and we carved us a dreadnought—a traditional Martin-style guitar. I gave that to him and he played that up to the day he died.”

Aesthetics hold great appeal for Hargiss.

“I’m fascinated by architectural design in what I create and in what I make. I study it.”

He called on every ounce of his heritage to lovingly restore a vaudeville-house-turned-movie theater. It came attached to the North Omaha buildings off Hamilton and 40th streets that he purchased five years ago. The theater lay dormant and unseen for 65 years, like a time capsule, obscured by walls and ceilings added by property owners, before he and his girlfriend, Mary Thorsteinson, rediscovered it largely intact. The pair, who share an apartment behind the auditorium, restored therbuilding themselves.

Preservation is nothing new to Hargiss, who reclaimed historic buildings in Benson, where his business was previously located. He was delighted to find the theater at the North O site, but knew it meant major work.

“I’ve always had this passion for old things. When we found the theater, I remember saying, ‘This is going to be a big one.’”

Motivating the by-hand, labor-of-love project was the space’s “potential to be anything you want it to be.” He’s reopened the 40th Street Theatre as a live performance spot.

Hargiss is perpetually busy between instrument repairs and builds—he has a new commission to make a harp guitar—and keeping up his properties. Someone’s always coming in wanting to know how to do something, and he’s eager to pay forward what was passed on to him.

The thought of working for someone else is unthinkable.

“I get one hundred percent control of my creativity. I’m not stuck. I’m not governed by, ‘Well, you can’t do it this way.’ Of course I can because the sound this is going to produce is mine. When you get to control it, then you’re the CEO, the boss, the luthier, the repairman, the refinisher, the construction, the engineer, the architect. You’re all of these things at one time.”

Besides, he can’t help making things. “There’s a drive down in me someplace. Whatever I’m working on, I first of all have to see myself doing it. Then I go through this whole crazy second-guessing. And then the next thing I know it’s been created. Days later I’ll see it and go, ‘When did I do that?’ because it takes over me, and it completely consumes every thought I have. I just let everything else go.” Encounter

Visit hargissstrings.com for more information.