Scanning any architectural periodical or blog, there are endless examples of buildings with clean lines, simple spaces, and minimal material pallets. Contemporary architecture owes much of this ethos to the modernist architects of the mid-20th century.

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe encapsulated the design philosophy with his famous quote: “less is more.” While turn-of-the-millennium McMansions of suburban Omaha represent the antithesis to the minimalism of midcentury modernism, the Omaha metro is home to several notable modernist residences designed by architect Neil Astle.

Two local homes designed by Astle came available on the market over the summer: the Flansburg Residence (located at 2205 S. 111th Circle) and the Ball Residence (located at 2525 S. 95th Circle).

r

r

r

Astle lived in Omaha between 1965 and 1981. During that time, he completed many award-winning architectural commissions, only a handful of which were homes. For his residential work, Astle said, “It is all part of refining a design in a complete way so that clients have few decisions to make—even about furnishings.” Dan Naegele, associate professor of architecture at Iowa State University, says, “They are more than houses. They are dwellings and are to be valued, cared for, basked in, and appreciated.”

r r

r

Theoretically, Astle was challenging something greater with his suburban homes. Naegele explains that the architect “removed the garage from the house, allowing its presence as a separate entity to create a complex. The remote, innocuous, naturally clad garage, though convenient to the house, was not part of the house itself. It allowed for the house to be low, and to be stretched across the site, rather than piled up in one place.”

The Flansburg Residence, located in the Rockbrook neighborhood, is a 2,500-square-foot home completed in 1969. Nancy Flansburg Novak, senior designer and partner at Alley Poyner Macchietto, grew up in the home and recalls her parents commissioning Astle to build the structure. She says, “my newlywed parents [Steve and Mildred Flansburg] were looking at homes, drove past Neil’s house, and stopped to ask who the architect was. He said it was him.” After a short exchange, the Flansburgs became Astle’s first residential clients. They also became lifelong friends.

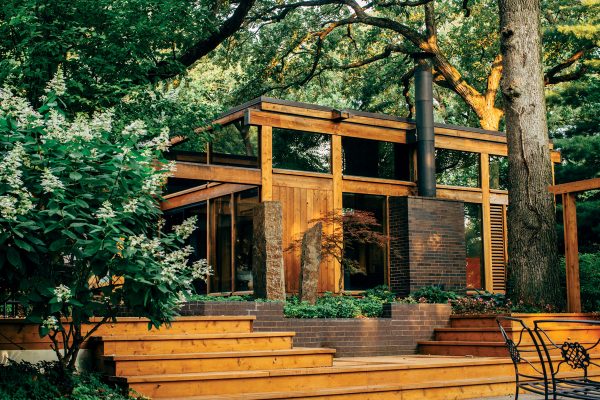

At the end of cul-de-sac, the split-level home sits surrounded by foliage. A carefully crafted foyer between the garage and home creates the first of many spectacular spaces. The patina of vertically clad western red cedar, a favorite material of Astle, fully wraps both units. According to Naegele, “[Astle’s] houses are all wood and because of this, they seem to exude authenticity.” This darker space sits in contrast to the light-filled living spaces.

r r

r

Entering the front door, creamy wool carpet and gray slate blanket the first level, which contains the living room and kitchen. An angular ceiling, clad in horizontal knot-free cedar, fills the entertaining areas with natural light. While the space is incredibly simple, phenomenal woodworking details by Bill Hayes are still in place. Subtle surprises are omnipresent.

Astle once said, “I try to get into families’ needs and express them thoroughly.” Going up or down a half or full level in the Flansburg Residence, Astle’s design philosophy becomes clear. Flansburg Novak recalls the home being “her jungle gym,” with plenty of nooks and crannies for her and her siblings. “It always felt big and open,” she says.

While Astle had free reign on the home’s design, the tight budget necessitated creative design solutions that come off as effortless. The efficient floor plan unfolds with neatly tucked away bedrooms, storage areas, exterior patios, and library. On the lower level, the ceilings were raised to allow the home’s patriarch to practice table tennis—many of his trophies remain in the library. The Flansburg’s home went on to win several awards, including a 1969 Residential Design Merit Award with the Nebraska chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

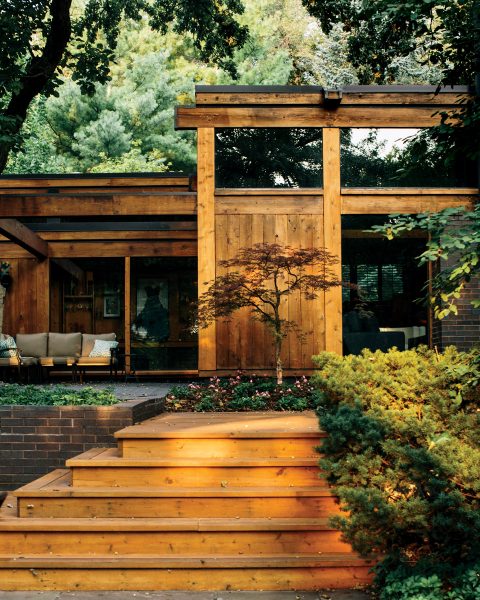

Less than two miles away on the edge of Towl Park, the Ball Residence extends many of Astle’s architectural tropes. Built in 1975 with the same cedar, owner Tami Doll (co-owner and vice president at Doll Distributing LLC) calls the home “a work of art.”

The 3,900-square-foot home features a detached garage, which contributes to the dramatic view of a courtyard where cedar and brick wrap the exterior and interior planes.

r r

r

r“When I walk in, there is a peacefulness about the home,” Doll says.

Upon entry, light fills the space, pulling full-scale picturesque views inside—suggesting continuity between human, architecture, and nature. Three bedrooms and entertaining spaces are neatly organized in an open floor plan and the same cedar covers much of the interior.

The original homeowners, Dale and Sylvia Ball, were quoted as saying, “The single most important decision in the whole process was selecting Neil as the architect.” Their instincts rang true when the home won the Honor Award for Distinguished Accomplishment in Architecture in 1975, as well as being written about in many national and international publications.

Recently featured in The New York Times (June 14) and academic literature, it is obvious that Astle’s work is significant, but as Doll notes, “I don’t think people realize homes like this are in Omaha.”

Astle’s works are “rare gifts to Nebraska,” Naegele says. These two residences—the Flansburg and Ball residences—offer a chance to reflect and remember how good his work was (and continues to be).

rThis article was printed in the September/October 2017 edition of Omaha Home. Learn more about Neil Astle’s work in the Omaha area in this article’s companion piece: “Neil Astle: Omaha’s Midcentury Modern Man”