The moxie of Nebraska’s new tourism slogan—“Honestly, It’s Not For Everyone”—reverberated across national media in late 2018, as reporters and talk show hosts reported the creative effort to influence travelers’ vacation plans.

The ad campaign follows bold Omaha and Nebraska tourism endeavors that have been getting the world’s attention as far back as the 1800s (for example, the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898).

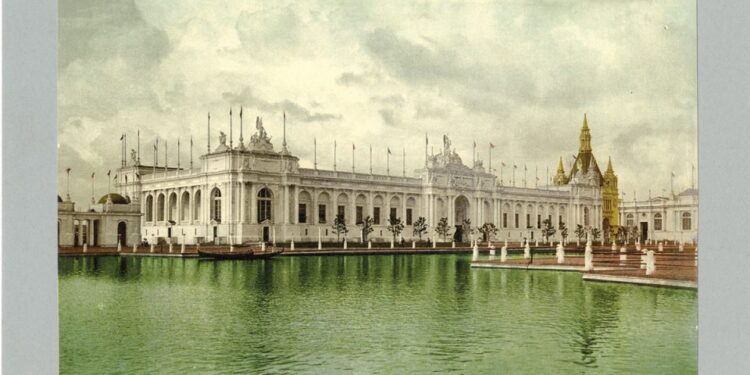

Omaha’s spectacular Trans-Mississippi Expo followed similar world’s fairs in London, Philadelphia, Paris, and Chicago. It was the first of several high-profile, high-risk events undertaken by state and city leaders, says David Bristow, editor of the state historical society’s Nebraska History Magazine.

Economic depression from the Panic of 1893 lingered into the late-1890s, and funding for the Expo seemed nearly impossible. But it also was an opportunity to jump-start the regional economy, showcase the West’s industrial growth, and highlight Omaha as a gateway to Western wonders, wrote Kenneth G. Alfers in his Nebraska History article, “Triumph of the West: The Trans-Mississippi Exposition.”

Funding was secured from a variety of means, and construction began in North Omaha on a breathtaking Venetian lagoon ringed by a courtyard of classically designed buildings and pavilions with displays sponsored by other states.

Incandescent lighting was incorporated everywhere along the Grand Court, in all buildings and along hundreds of poles, lit by a specially constructed power plant. It was the largest display of the new technology up to that time. The nightly brilliance symbolized the West’s high-tech progress, wrote Amanda N. Johnson in her Nebraska History article, “Illuminating the West: The Wonder of Electric Lighting at Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898.”

r r

r

Despite the Spanish-American War’s breakout, the great illumination helped draw 2.6 million people over the fair’s five-month run, many traveling by rail from the West, East, and internationally. Sightseers took home stories of Omaha’s marvels, and newspapers nationwide proclaimed the Expo’s greatness, wrote Johnson. A visit by President William McKinley at the fair’s end drew nearly 100,000 people and also generated vast publicity, Bristow says.

Nebraska followed the Expo’s success with another tourism first at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, says Paul Eisloeffel, curator of audiovisual collections at the Nebraska Historical Society.

Motion picture technology had come to Nebraska a year prior to the 1898 Expo, where Thomas Edison’s films of American soldiers during the Spanish-American War were shown. It was also at the Expo that a motion-picture camera first photographed Nebraska scenes, including a now-lost film of President McKinley’s visit, wrote Andrea I. Paul in her article, “Nebraska’s Home Movies: The Nebraska Exhibit at the 1904 World’s Fair.”

Nebraska decided to promote itself at the St. Louis World’s Fair (aka the Louisiana Purchase Exposition) through a film series instead of a traditional agricultural exhibit, Eisloeffel says. Highlights included farmland scenes such as harvesting, cattle, and cowboys, as well as the University of Nebraska campus, state fair, Ak-Sar-Ben activities, and downtown Omaha.

To stay within budget, Nebraska opted not to construct its own building at the fairgrounds—the only state not to do so—instead creating a theater within the agricultural building. It was an immediate success. Initially planned to be shown twice daily, the films soon were viewed continuously. The theater was expanded, and daily attendance surged to 2,000, wrote Paul. The series subsequently was shown at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, Oregon, where the press reported the films drew hundreds daily and created “the same enthusiasm they produced in St. Louis last summer.”

Two more large-scale events—Nebraska’s Diamond Jubilee in 1929 and Omaha’s Golden Spike Days a decade later in April 1939—were wildly successful despite taking place during tough economic and political times, Bristow says.

The Jubilee celebrated the 75th anniversary of the opening of Nebraska Territory to settlers in 1854. Capped by a two-mile-long “Parade of Nations,” the Omaha event drew about 150,000 despite the Wall Street Crash and start of the Great Depression just a week earlier.

Similarly, Golden Spike Days came on the heels of the Depression and just prior to the start of World War II. Held in the city from which the transcontinental railroad originated, the event celebrated the premiere of director Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific movie epic. For four days, Omahans and their out-of-town guests were transported back to the 1860s, with blocks of fake storefronts populated by men in long whiskers and ladies in gingham dresses, says Patricia LaBounty, curator of the Union Pacific Historical Museum. Thanks to publicity churned out by the Hollywood press, more than 200,000 people showed up along the downtown parade route, cheering dignitaries and movie stars such as Barbara Stanwyck.

Many tourists arrived via Nebraska’s improving highway system, which had come a long way since visitors to the Trans-Mississippi Expo first beheld an “electric carriage” exhibited by Montgomery Ward & Co. By 1912, Nebraska ranked first among all states in per capita ownership of autos, with one vehicle registered for every 45 people, wrote L. Robert Puschendorf in his Nebraska History article, “Lifting Our People Out of the Mud.”

Three of the earliest automobile trail associations, all organized in 1911, promoted routes crossing Nebraska, including the Meridian Road from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. By 1913, the coast-to-coast Lincoln Highway was mapped, with Nebraska as the lynchpin between New York City and San Francisco. Years later, the state would be the first in the nation to complete its mainline interstate system.

Today, tourists are invited to exit off that interstate, to look deeper and discover what makes Nebraska so special.

r

The Nebraska Historical Society features articles from Nebraska History Magazine on its website. Visit history.nebraska.gov for more information.

A History of Tourism Slogans

r

Here’s a look back at Nebraska’s tourism and state slogans from the 1970s through today, according to the Nebraska Tourism Commission:

“Nebraska…The Good Life”r(1972-1975)

“Rediscover Nebraska During the Bicentennial”r(1976)

“Nebraska…The Good Life”r(1977-1978)

“Vacation Nebraska”r(1979)

“Nebraska…Delightfully Different”r(1980-1981)

“Nebraska…Discover the Difference”r(1982-1985)

“My Choice, Nebraska”r(1986)

“Celebrate Nebraska”r(1987)

“Come See What We’re Up to Now”r(1988-1991)

“Send a Postcard from Nebraska”r(1992-1997)

“Genuine Nebraska”r(1998-2001)

“America’s Frontier”r(2002-2003)

“Possibilities…Endless”r(2004-2013)

“Visit Nebraska. Visit Nice.”r(2014-2016)

“Nebraska Through My Eyes”r(2017-2018)

“Nebraska: Honestly, It’s Not for Everyone”r(2019)