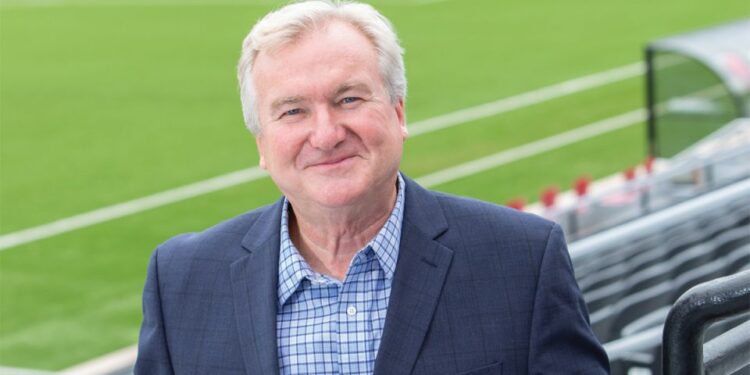

Bob Warming’s unexpected return to Omaha in 2018—this time to head the men’s soccer program at the University of Nebraska-Omaha—is the latest turn in a lifelong love affair with coaching.

Warming, 64, twice helmed the Creighton University program in town. He’s known as the architect of a Bluejay program he took from nothing to national prominence. During his first CU run (1990-1994), Omaha became home to him, his wife Cindy, and their four children. During his second CU tenure (2001-2009), his kids finished school and came of age.

His passion for the game is such that even though he’s one of collegiate soccer’s all-time winningest coaches at an age when most folks retire, he’s still hungry to lead young people. After eight highly successful seasons at his last stop, Penn State, he did retire, albeit for less than two months, before taking the UNO post in April.

Love for family changed best-laid plans. It started when he and Cindy visited Omaha in November to meet their new granddaughter. Their intense desire to see her grow up caused Warming to step down at Penn State and move to Omaha.

When then-UNO soccer coach Jason Mims decided to pursue new horizons (Mims had played and coached for Warming at Saint Louis University, and traveled with him to Creighton and Penn State before kickstarting the UNO program in 2011), Warming couldn’t resist continuing to build what his former assistant had started.

“I have come back with even more energy. There’s a lot of younger guys I’m running into the ground,” Warming says.

He also brought knowledge gained from legendary peers and best friends at Penn State: women’s volleyball coach Russ Rose, wrestling coach Cael Sanderson, and women’s soccer coach Erica Dambach.

“I learned more coaching at Penn State than I had in all my previous years,” he says. “It’s not even close. I grew tremendously. I got a lot of new ideas about things. I derive tremendous energy from being a continual learner. Even in the 59 days I retired, I continued to research better ways to teach and train people.”

His son, Grant, played for him in Happy Valley and now assists at UNO. Grant’s twin sister, Audrey, died in a 2012 auto accident. The family honors her legacy with Audrey’s Shoes for Kids, an annual event that gives away soccer shoes, shin guards, jerseys, and balls to disadvantaged children in Omaha. About 300 youths received gear in this summer’s giveback.

Warming first fell in love with coaching at age 14 in his native Berea, Kentucky. The multi-sport athlete was a tennis prodigy on the United States Lawn Tennis Association’s junior circuit when his coach taught him a lesson in humility by having him coach 9-year-olds. In the process, Warming found his life’s calling.

“I had been very into myself only,” he admits. “I was a selfish little brat. Then all of a sudden I realized it’s about helping other people. It’s a great lesson my coach taught me. He knew if I was ever going to go any place with my life, I had to give something to others.”

Warming’s outlook on life gradually shifted. “I derive the most pleasure out of watching young people improve,” he says.

Soccer supplied his next life-changing experience. Berea College, a private college in his hometown, has a long history of inclusion. In the early 1970s, it recruited world-class footballers from Ghana and Nigeria. Warming was the squad’s goalkeeper (and also a varsity letter-winner on the tennis, swimming, and golf teams); he honed his knowledge of soccer from these foreign players and gleaned insights into diversity.

“I’m playing soccer and hanging out all the time with these black guys in the South—not the most popular thing to do in a town where on Sunday nights every summer the KKK burned a cross,” he recalls. “That was the dark ages in a lot of ways. But I was fascinated interacting with these guys from Africa and finding out how they live and what their culture is like.

“I was able to play with these incredible guys from a young age, and the game is the best teacher,” he says. “For me, it was a remarkable time in my life. I learned a lot about a lot of different things.”

Years later at Penn State, he brought more student-athletes of color into the soccer program than it had ever seen before. “That was a cool part of the whole deal,” he says.

He appreciates what a mentor did in giving him a progressive outlook. “The guy who eventually became my college coach was the leader of all this,” Warming says.

His own collegiate coach at Berea, Bob Pearson, succeeded his protégé a few years later when Warming left his coaching post at Berry College in Mount Berry, Georgia, for a coaching position at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte in the 1980s. Four decades later, the veteran Warming succeeded his own protégé, Mims, at UNO.

“I have all these crazy circles in coaching,” he says.

The kind of bond Warming has with Pearson, he has with Mims.

“Loyalty, trust, and respect are the basis for all relationships, and we have all three of those,” Warming says.

Pearson got Warming his first head coaching gigs in his 20s at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky (where Warming spent one season before heading to Berry University); he also coached tennis at both schools.

Warming was still only in his mid-30s when Creighton hired him the first time in 1990, poaching him from his brief tenure as director of athletics at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. At Creighton, he revived a dormant program that began winning and drawing fans.

He enjoyed the challenge of “building something from its inception and doing missionary work for our sport.” In exchange for free coaching clinics, he got local soccer clubs to turn out in droves.

“Thus, Creighton soccer was born. It came out of giving back to the community and coaching education,” Warming says.

He left CU in 1994 for Old Dominion. From there he went to Saint Louis University. The Rev. John Schlegel, then-CU president, lured him back in 2001 with the promise he could design a state-of-the-art soccer facility.

“Father Schlegel said, ‘Build me a soccer stadium. We want an iconic building to define the new eastern borders of our campus. I’ll pick the facade because I want it to reflect how the rest of the campus will look,’” Warming recalls. “Think about that. Where else has a soccer stadium determined what the rest of the campus would look like?”

The result, Morrison Stadium, has become a jewel of north downtown.

Warming’s CU and Penn State teams contended for conference and national titles. Now that he’s back in Omaha, he looks to take fledgling UNO soccer to its first NCAA playoff berth and create a powerhouse like the one he did down the street.

Back in Omaha again, he organized “the largest free coaching clinic in the country” at UNO in August. Some 200 coaches from around the nation attended, including 150 from Nebraska. Tweets about the event surpassed two million impressions.

“The selfish reason I did it was I want to kick-start this program into something, and to take soccer in Nebraska to the next level,” he says. “We have to get better.”

His methods today are different than when he last coached in Omaha.

“If you really want to train people, you have to get them in the mood to train using all the different modalities—texting, tweeting, playlists, video—available to us now,” he says. “You cannot coach, you cannot lead, you cannot do anything the way people did it years ago. You won’t be successful. The why is so important in terms of explaining things and building consensus and getting people involved to where they say, yeah, we want to do this together.”

In the full circle way his life runs, he feels right at home at UNO, where hundreds of students, including international students, get a free education. “We are the school of the people,” he says.

Meanwhile, he’s busily stocking his roster with players from around the globe—including France, Spain, and Trinidad and Tobago—with many more players from Omaha and around the Midwest.

Wherever he’s landed as a coach, it’s the new challenge that motivates him. No different at UNO. “One hundred percent,” he says. “I love it.”

Visit omavs.com for more information.

This article was printed in the November/December 2018 edition of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.