The decades-long rise of Sears, Roebuck & Co. to the country’s largest retailer, and its recent collapse into bankruptcy, reflects more than a shift in American consumer preferences.

Sears was an important part of life in America’s frontier, and its iconic catalog provided access to conveniences and essentials, including the roof over many people’s heads. The catalog flourished after the Homestead Act, the growth of railroads, and postal reforms such as special rate classifications and free rural delivery.

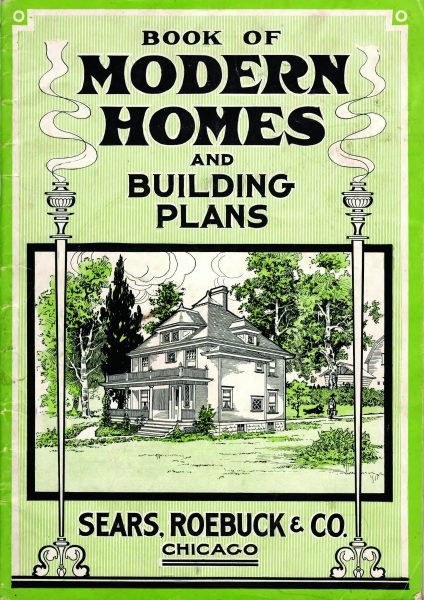

The first Sears, Roebuck & Co. calendar hit mailboxes in 1894 and was followed over the next few years by specialty catalogs and color sections. In 1908, the catalog began offering ready-to-build homes. Customers would receive a railcar filled with precut lumber and the necessary supplies and instructions to build a home, or hire a company to perform the assembly, at a fraction of the cost of a custom-built house.

r r

r

Sears estimates more than 100,000 homes were sold between 1908 and 1940 through its Modern Homes program. Thousands of these homes have survived to this day, including one known example in Omaha’s Miller Park neighborhood.

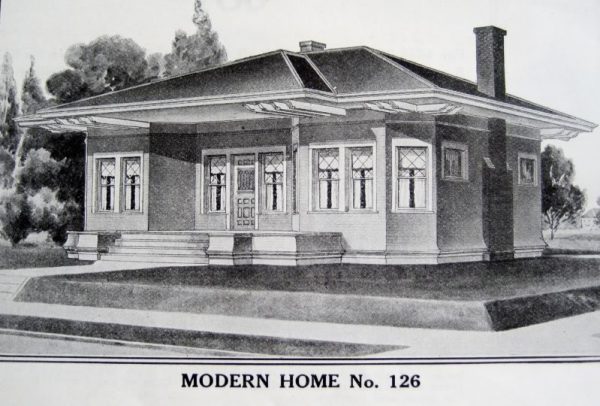

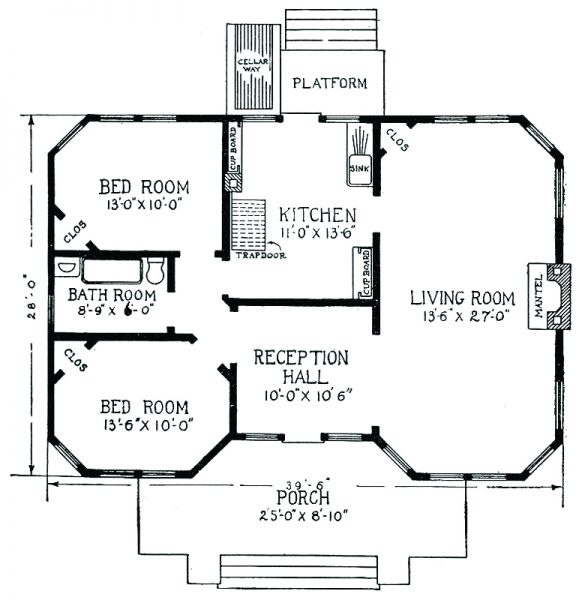

That 1920 house on Meredith Avenue is Sears Model Home No. 126, according to Sarah Addleman, who recently finished a master’s thesis on identifying Sears homes. She says Omaha likely has other examples, but they can be tricky to identify because most homes of that age—the youngest Sears kit house would be more than 70 years old—have undergone additions and remodeling.

Addleman says Sears was far from the only company manufacturing kit homes.

“They didn’t even sell the most units,” Addleman says. “It’s almost like Kleenex—Sears has become synonymous with kit houses. Even if they’re one of the other houses, people still remember it in the folklore as a Sears house.”

Sears and other kit-home companies modeled their homes off popular styles at the time, including those of pattern-book designs.

Pattern-book houses are structures for which architects would sell stock plans for homes to help cut costs. Many pattern-book houses can be found throughout the Minne Lusa neighborhood. Everett S. Dodds was an Omaha architect who sold stock plans, and History Nebraska says 78 homes are attributed to him.

With several factors at play, it can be hard to distinguish a Sears house or a pattern-book house from other builds from the same era.

“One house could be a Sears house, and the one next door could be a custom home,” Addleman says.

Official property and mortgage records can be helpful, although sometimes old files go missing, which was the case when Ed Quinn went to continue his research on the original city permits for Omaha’s Field Club neighborhood about a decade ago.

“Some clerk threw them out accidentally,” Quinn says.

Quinn led the effort to establish the Field Club Historic District with the National Register of Historic Places. His research explored the origins of the neighborhood, and he came up with a list of suspected kit homes.

“If it wasn’t an architect-designed or building-designed home, there was a good chance it was going to be a one-off or it could be a kit home,” Quinn says.

r r

r

Quinn wrote an article on kit homes for the neighborhood’s newsletter in 2001. He said several neighbors told him they suspected their homes began as kits, which were popular when the Field Club neighborhood was being built.

“This was a more wealthy neighborhood,” Quinn says. “This was Omaha’s first suburb, so to speak. It was connected by the trolleys.”

Addleman says she’s looked at homes in the Field Club neighborhood and didn’t find any that matched known models of Sears homes.

To examine your own home, Addleman suggests looking for stamped lumber in the attic or unfinished basements, especially in the middle or end of the joist. She said Sears had a specific stamped mark, and pieces were assembled by number.

“It wouldn’t just be like a grease pencil mark,” Addleman says. “It would say A38 or something similar to that.”

Don’t rely on light fixtures or plumbing, because those components were sold outside the kits as well, she says. Websites can provide a lot of tips on what to look for, or it is possible to bring in someone for an authentication.

“There are experts out there who are willing to come to people’s homes,” Addleman says.

Despite the closing of the Sears store at Crossroads Mall, which marked the retailer’s departure from the Omaha market after 90 years, Sears hasn’t completely left Nebraska. The company still operates a handful of hometown stores in communities such as Columbus, Fremont, Kearney, and Norfolk. Those stores have a smaller footprint and specialize in appliances, tools, and lawn and garden items.

The company also still operates about 400 stores nationally, but it’s struggling with a new concept for a limited version of its flagship department stores. It may be the end of an era for Sears, but its history is being preserved one home at a time.

“They are a part of our heritage, so they are worth protecting and saving,” Addleman says. “Sears is a part of Americana.”

r

Visit searshomes.org for more information.r

rThis article was printed in the July/August 2019 edition of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.