If you’ve spent any time in Omaha, you know the voice. The voice. It’s been in your head since the 1970s. It was in your head at the height of album rock, back when the pot haze up in the rafters of the Civic Auditorium got you higher than… well, the rafters of the Civic Auditorium. The voice invited you there and you followed the voice there and there on that Best Day Ever you experienced Eddie Van Halen shredding the Frankenstrat and your eardrums. Dude, seriously, Otis XII might have spoken to you more than your own mother. And since he was probably the coolest guy you knew, since he was always there for you, he may be the guy you’re still trying to be.br

The voice still fills a room at 64 years of age. It even fills the back yard of his home near Maple Street and I-680. This writer first heard the voice on his Pioneer SK95 boom box back in the early 1980s nearly 100 miles southeast of Omaha. Riding the Z-92 waves the voice reached even the hinterlands of Eastern Nebraska.

br

Here on the patio, the voice that filled a yesteryear of pimples and awkwardness and premature-everything carries pretty much that same memorable tenor. Let’s say it hovers in the low G range: Resonant like the deep bong of a wind gong. But, alas, the vocal chords, thanks to his last active addiction—smoking—have been scraped ragged. There is gravel now. We’ll call it character.

brbr

Really, the gravel fits the man behind the voice. Somehow, this guy brought a soothing heft to the locker room heckling of FM radio. He was funny, but there were strong suggestions of the Jesuit upbringing, the formative years spent in a monastery, the love for Continental and Eastern philosophies, the years on the road, and maybe, a collection of scars. The guy wasn’t heavy, really. He just had a heft and thoughtfulness unusual for the morning drive. Even the absurdities had a hint of gravity. It is a mind and voice that arguably better fits his current job. He is the voice of UNO’s KVNO radio. Classical music. No way is this guy classy. But he is still pitch-perfect for the refined.

br

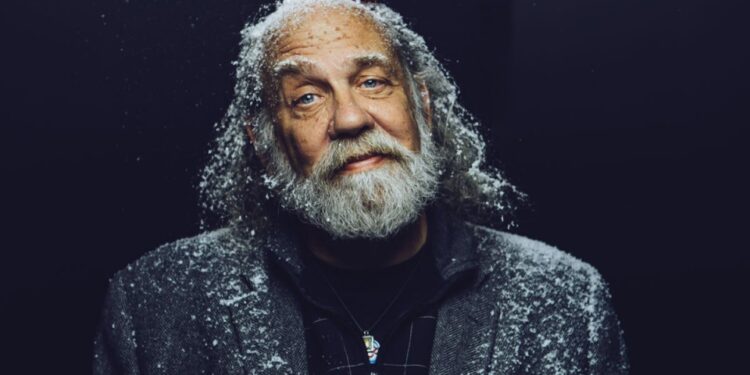

As for his face—damn. Rasputin? “I got the face I deserve,” he says. Is “fugly” too strong a term? This is not the face of a man without sin, woe, and hard-won experience. If you are of a certain bent, though, this is the roadmap face of a fellow you really want to explore.

br

Much of his story’s arc is funky cool and full of holy-cow moments, but, ultimately, kinda what you’d expect from a roaming hippie, travelling-show-minstrel-turned-radio-star that is now the sagely, sedate, wisely-sober-but-not-overly-AAish voice of a cultured non-profit. The chronology: college shenanigans. Electric Bathwater. Haight-Ashbury. Crazy hippie sh*t. Dr. Demento. Good Times. The Mean Farmer. Space Commander Wack. Bad behavior. Worse behavior. Rehab. Family life restored. The middle-age writing phase. Lots of memorabilia. Mozart. The occasional charity event. All great campfire fare.

br

But underneath all of this, there was always a horrible secret festering. This other story is heartbreaking and messed up. When the drinking stopped in the late 1980s—when things slowed down and the self-medicating stopped—a monster returned. Here is where the story turns.

br

At this point, we’ll call him by his birth name, Doug Wesselmann. This was his name when he was 12 years old and the man he most trusted from church took him for a ride.

br

He was that cool older friend.” The guy drove a cool convertible with duel pipes and a nice stereo. “It all lured me in—that’s how predators operate,” Wesselmann says.

br

It happened out on a quiet county road not far from Wesselmann’s home in Kansas City. The guy took him for a ride, then parked unexpectedly. Wesselmann understandably truncates details. He’ll say this much: The man raped him, strangled him, and left him for dead in a ditch. Wesselmann awoke and staggered home dazed with an aching throat and blinding headache. At his house, he washed himself off with a garden hose and went inside. His father, who travelled often for business, wasn’t there. His mother was asleep. He didn’t speak in detail about the attack for more than 30 years.

br

A few months after the attack, Wesselmann left for Atchison, Kansas, to enter the Benedictine monastery there. Each day until he graduated from secondary school he spent time in the strict silence demanded by the Rule of St. Benedictine. The monks believe silence clears the mind of distractions.

br

He came to Omaha in the mid-1960s to attend Creighton University. He was steeped in church teaching, he loved philosophy, but the priesthood, as any longtime listener might guess, was not for him. At Creighton, he started a counter-culture radio show on Creighton’s university station that regularly rankled the Jesuits.

br

Along with his friends, Wesselmann gravitated toward programs “with this really odd mix” of music and comedy. Skits, weird characters, the latest trippy music. The names of the shows and troupes were psychedelic and inspired. (“The Electric Bathwater,” for one). In 1970, Wesselmann, Bill Frenzer,” and Bill Carey formed the music and comedy troupe “The Ogden Edsl Wahalia Blues Ensemble Mondo Bizzario Band,” a name they wisely shortened to “Ogden Edsl.” Weird, satirical, and often quite dark (one of their biggest hits was “Dead Puppies”), the group was often featured on the nationally syndicated “Dr. Demento” radio show based out of Los Angeles. In fact, “Dead Puppies,” became the most requested song in the history of “Dr. Demento.”

br

Wesselmann lived “hand-to-mouth” off of his band earnings in the San Francisco of the early 1970s. Life was “pretty much what you’d imagine” for a travelling comedy and music troop in that era. “We weren’t making much, but, you know, we were actually making a living doing that stuff,” Wesselmann says. “It’s something every young person should do.”

br

Through this time, he says, the trauma from the attack in his adolescence stayed neatly packed away. His lifestyle, he says, helped keep anything unpleasant at bay. “Drugs and alcohol can work great for a while.”

br

By 1977, though, Wesselmann decided it was time to move on. He wanted to marry and have kids— “that whole thing.” He moved back to Omaha. Here, his good friend, artist Kent Bellows, introduced him to his sister. “I guess Kent thought we were good breeding stock.” Doug and Deb have been married for 37 years.

br

Upon arriving in Omaha, Wesselmann quickly teamed up with a like-minded comedian named Jim Celer, who picked up his own moniker, “Diver Dan Doomey.” The duo started with a weekly show on rock station KQKQ. They were then asked to do the morning show for a new Omaha rock station, KEZO-FM. Z92 took off thanks to their morning show and what Wesselmann calls a “genuinely superb staff.”

br

The ride lasted 13 years.

br

Through the 1980s, in the background, Wesselmann drank. He lived the substance-abuse cliché: He kept a balance for years, then he increasingly didn’t. He started damaging his relationships. “Drugs and alcohol worked for a long time, and then they stopped working but I kept using. That’s the stage there where you put everyone around you in pain. The usual process.” Wesselmann entered rehab in 1989. He has been sober for a quarter century.

br

Flipping through the dial here: In 1992, he went to KFAB. In 1993, CD-105. After six years, he started doing talk radio for KKAR. In 2001, not long after September 11, Wesselmann left KKAR. “After 9/11, everything became jingoistic. You were expected to provoke, not inform. That’s what made money. It just wasn’t for me.”

br

He and Deb moved 54 miles east of Omaha to Walnut, Iowa. At the time, Wesselmann was increasingly becoming known for his short stories. After leaving radio in 2002, he turned his attention to writing fiction and essays. His first novel, On the Albino Farm, was shortlisted for the 2003 British Crime Writers Association “Debut Dagger Award.”

br

Other pieces, A Prozac Notion, The Goodness of Trees, and On the Albino Farm all won significant prizes. Wesselmann, for whatever reason, was particularly popular and critically-acclaimed in England.

br

But, his royalty checks looked like those of most fiction writers. In 2006, the family moved back to Omaha and Wesselmann took his current job with KVNO.

br

Although he no longer writes fulltime, Wesselmann says he is not finished with writing. He has journaled all his life. He continues to journal. He journaled heavily once the night terrors began back in the mid-1990s.

br

Now, he and Deb have begun writing a book together. Deb is a psychologist who works with trauma victims (this isn’t why the couple met). Their book will be an amalgam: She will discuss methods of coping and working past PTSD, he will provide interludes in poetry and essays from the perspective of someone who has been wounded by trauma.

br

He will be telling the story of how he found peace. He will also tell the story of the day he went hunting for his attacker.

br

The night the couple met, Deb says, “I really had no intention of ever seeing him again. He was trying to impress me with his knowledge. We got in a big fight. I told my brother (Kent Bellows) that he was the most obnoxious person I had ever met.”

br

Needless to say, her opinion softened in subsequent meetings. The couple married and had children. Work and family life was all-consuming.

br

Through the 1980s, Doug marched through the stages of addiction. A few years after he got sober, Deb left teaching to pursue a master’s degree in psychology. She wanted to work with traumatized children, in particular. It was “just strange coincidence” that, “somewhere around 1994, [Doug] started giving these hints that something was wrong—that something happened at some pointbrin the past.

br

“There was no longer the self-medicating. He didn’t have that crutch. He became more easily agitated. The night terrors really floored him. It was awful for him, it was really awful to live with for both of us. There were all the symptoms of [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder].”

br

He finally told her the details of the attack. He sought therapy. He meditated. He journaled. “The process was pure drudgery, two steps forward, one step back,” Deb says. “Five years. Finally, he started reaching some level of peace.”

br

For the most part, Doug says, the years in Walnut and the years with KVNO “were the most peaceful of my life.” But there was still an unresolved issue: Where was his attacker?

br

Two years ago, against the wishes of his wife, Wesselmann took a trip back to the monastery in Atchison, Kan. He wanted to talk to the priest who helped cover up the crimes of his attacker. He says he honestly couldn’t predict his reaction if he found out where his attacker lived. “I assumed I could make peace with it. I don’t know.”

br

Wesselmann found the priest. He told the priest that he wanted to go to confession. Wesselmann had a plan: “In a confessional, it would be very difficult for him to lie. Did the priest feel any remorse? Where was the guy? I just wanted to know.”

br

He found what he was looking for: “There was heartfelt remorse.”

br

And then…

br

“The priest tells me that the guy wrapped his car around a tree. Dead. Done. Maybe it’s what he deserved. I don’t know. But he was dead.”

br

“There was a whole new serenity to him when he came back,” Deb says.

br

Now Doug and Deb are in the process of co-writing a book on overcoming severe trauma. As co-founder of The Attachment and Trauma Center of Nebraska, Deb has helped hundreds of victims of trauma find peace. In her portion of the book, she’ll provide a toolbox for trauma victims.

br

And Doug “will be doing the right-brained stuff.” Interwoven with her expert advice (Deb has already written three books herself) will be his essays and poems—some humorous, some decidedly not—detailing and ruminating on his journey. The couple is in the beginning stages of writing and compiling.

br

Maybe the book succeeds. Maybe it doesn’t. “It’s not going to change things either way,” he says. “I’m where I want to be.”

br

“Since that trip to Atchison, he’s really been at more peace in his life than ever,” Deb says. “I put that in the category of a ‘miracle.’ Considering where he was—truly, deeply tormented—to where he is now, it’s difficult not to call all of this a miracle.”

This article was first published in the November/December 2014 issue of Omaha Magazine.