Xenophobic fears ran wild after the Empire of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The U.S. promptly entered World War II, and nearly 120,000 Japanese-Americans were relocated or incarcerated in internment camps across the country.

The Rev. Edward Flanagan, the founder of Boys Town, strived to calm the hysteria in part—while alleviating the trauma falling upon his fellow Americans—by sponsoring approximately 200 Japanese-Americans from internment camps to stay at his rural Nebraska campus for wayward and abandoned youths.

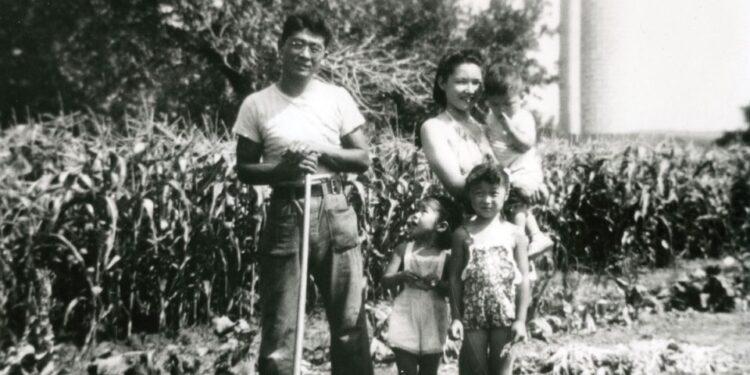

Among them were James and Margaret Takahashi and their three children.

They joined the individuals and families escaping to Boys Town from prison-like internment camps. Flanagan offered dozens of families a place to live and work until the war’s conclusion. Some remained in Nebraska long after the war. Many used Boys Town as a stopover before World War II military service or moving to other American cities and towns, says Boys Town historian Tom Lynch.

Few outsiders knew Boys Town was a safe harbor for Nisei (the Japanese word for North Americans whose parents were immigrants from Japan) who lost their homes, livelihoods, and civil rights in the fear-driven, government-mandated evacuation of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast.

The oldest Takahashi child, Marilyn, was almost 6 when her family was uprooted from their Los Angeles home and way of life. Her gardener father lost his agricultural nursery.

“It was a very disruptive thing,” she recalls. “I was very upset by all of this. I can remember being confused and wondering what was going on and where are we going. I couldn’t understand all of it.”

She and her family joined hundreds of others in a makeshift holding camp at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. Stables at the converted race track doubled as spare barracks. Food riots erupted.

By contrast, at Boys Town, the Takahashis were treated humanely and fairly, as the full citizens they were, with all the comforts and privileges of home.

“We felt welcomed and did not have fears about our environment. The German farmers nearby were friendly and kind,” remembers Marilyn Takahashi Fordney.

The Takahashis were provided their own house and garden within the incorporated village of Boys Town’s boundaries. James, father of the family, worked as the grounds supervisor. The children attended school. The family celebrated major holidays—including unforgettable, bittersweet Christmases—in freedom, but still far from home.

None of it might have happened if Maryknoll priest Hugh Lavery, at a Japanese-American Catholic parish in L.A., hadn’t written Flanagan advocating on behalf of his congregation then being relocated in camps. Flanagan recognized the injustice. He also knew the internees included working-age men who could fill his war-depleted employee ranks. He had the heart, the need, the facilities, and the clout to broker their release from the Civil Exclusions Order signed into law by President FranklinrDelano Roosevelt.

Helping identify “good fits for Boys Town” was Patrick Okura, who ended up there himself, Lynch says. “It sort of started a pipeline to help bring people out,” and Flanagan “eventually took people of all different faiths,” not just internees from the Catholic parish that started the effort. “People from that parish went to the camps, and they met other Japanese-Americans, and they started communicating about this opportunity at Boys Town to get out of the camps.”

During her family’s four-month camp confinement, Marilyn’s parents heard that the famous Irish priest in Nebraska needed workers. James sent a letter making the case for himself and his family to come.

“People could leave if they had somewhere to go,” Marilyn says. “Permission didn’t come right away. It took writing back and forth for several months. Then, when we were all about to be moved to Amache [Granada War Relocation Center] in Colorado, the head of our camp sent a telegram to the War Relocation Authority. He received a telegram back with the necessary permission. We were released to Boys Town Sept. 5, 1942.”

Boys Town became legal sponsor for the new arrivals.

“It was very radical helping these people,” Lynch says. “Father thought it was his duty because they were good American citizens who should be treated well. But it wasn’t universally accepted. What made Boys Town unique is that we were way out in the country, so we were our own little bubble. Visitors really wouldn’t see the internees much. The men worked the farm or grounds. The women tended house. The kids were in school. But they were there all throughout the village.”

A similar effort unfolded at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where 100-plus Nisei students continued their college studies after the rude interruption caused by the “evacuation.”

During her Boys Town sojourn, Marilyn first attended a nearby one-room public school. She later attended a school on campus for workers’ children taught by a Polish Franciscan nun. Besides the standard subjects, the kids learned traditional Polish folk dances and crafts.

The Takahashis started their new life in an old farmhouse they later shared with other arrivals. Then Boys Town built a compound of brick houses for the workers and their families. “Single men lived in a dormitory on campus,” Lynch says. “Boys Town didn’t host many single women because Father would find jobs for them in Omaha, where they would stay with families they worked for as domestics.”

From Santa Anita, the Takahashi patriarch was allowed to go to L.A. to retrieve his truck and what stored family belongings he could transport. James drove to Nebraska to meet Margaret and the kids, who went ahead by train.

Marilyn’s initial impression of Flanagan was of Santa Claus with a cleric’s collar: “Father came to meet us at the station. He had this big brown bag of candy. I will always remember that candy. It was so thoughtful of him to give us that special treat.”

According to the Takahashi family’s file in the archives of the Boys Town Hall of History, Margaret said she was taken by Flanagan’s humanity, that she “could feel this warmth. I’ve never felt that from another human being. He was so full of love that it radiated out of him.”

According to Lynch, Flanagan considered the newcomers “part of the family of Boys Town.” They could access the entire campus or go into town freely.

Leaving altogether, though possible, was not a realistic option.

“They could leave at any time, if they really wanted to, but there was nowhere to go [without authorization]. They would have been detained and returned,” he says.

Marilyn’s experience of losing her home and living in a camp was dreadful. Going halfway across the country to live at Boys Town was an adventure. Her fondest memories there involve Christmas.

“Christmas and midnight Mass was very special at Boys Town,” she says. “It was something we looked forward to. I will always remember getting bundled up to face the blizzard-like winds. My father would carry each one of us to the truck. We would head off in the dead of night in that blasted cold to get to the church, which was dark except for the altar lights. The boys would be in a long line in their white and black cassocks, with red bows, each holding a big lit candle. They would begin to sing and come down the main aisle. It was an awesome sight and a special experience. The choir was exceptional. There was always one singer with a high-pitched voice who did a solo. It was amazing.”

Flanagan is part of her holiday memories, she says, as “he always made a point to come to our Christmas plays, and we would always take a photograph with him.” For the resident boy population, Flanagan “played” Santa by visiting their apartments and handing out gifts.

“We were happy at Christmas,” Marilyn says. “In the farmhouse, my father would cut a pine tree and bring it in, and the decorations were handmade and hand-painted cones with popcorn strung. He always did the final placement of things so that it looked perfect. We had wonderful Christmas days even though it was difficult to get toys because many things were not available due to the war.”

She continues: “We built an ice rink and would skate in front of the farmhouse or in front of the brick house. We even made an igloo one time. It got so tall the adults came out to help us close the top with the snow blocks because we were too little to reach it.”

Weather always factored in.

“The summers were extremely hot and the winters so severely cold,” she says. “We had never experienced snow. That was a tremendous adjustment for my parents. But, as children, we delighted in it. We’d run out and eat the snow with jam and build snowmen.”

Marilyn recalls visiting Santa at J.L. Brandeis & Sons department store in downtown Omaha with its fabulous Christmas window displays and North Pole Toy Land.

The Takahashis were content enough in their new life that they arranged for family and friends to join them there. Marilyn and family remained in Omaha for two years after the war (and anti-Japanese hysteria) ended.

“Eventually, my parents decided they couldn’t withstand that cold, and we headed back to California in 1947,” she says.

They endured tragedy at Boys Town when Marilyn’s younger brother contracted measles and encephalitis, falling into a coma that caused severe brain damage. His constant care was a burden for the poor family.

Another motivating factor for the family to leave was the father’s desire to work for himself again.

Leaving Boys Town just shy of age 12 was hard for Marilyn.

“I was heartbroken because I loved the snow and cold and all my friends there,” she says. “I did not want to go to California and live three families to a house and struggle. I knew what was coming. I also had a pet cat I was sad to leave. My pet dog Spunky that Boys Town gave me had passed on.”

Her parents had also bonded with some of the resident boys, and with some adult workers and their families.

“We went by Father Flanagan’s residence to say farewell, and he came out to bless us and to bless the truck we drove to the West Coast,” she says.

As an adult, Marilyn shared her story with archivists just as her parents did earlier.

“We considered ourselves fortunate,” Margaret told interviewer Evelyn Taylor with the California State University Japanese American Digitization Project in 2003. (This article for Omaha Magazine merged excerpts from that oral history with original interviews conducted over the telephone andre-mail correspondence.)

There are occasions when Marilyn’s internment past comes up in casual conversation. “It is amazing how few people know about this,” she says. “It is now mentioned in history books in schools, but it wasn’t for a long time.”

When she brings up her Boys Town interlude, she says, “It is always a surprise and I am asked many questions.”

The retired medical assistant, educator, and author now runs family foundations supporting youth activities. She credits her many accomplishments to what the wartime years took away and bestowed.

“The internment made me an overachiever. Because I was the eldest and experienced so much, I have become actually the strongest of the siblings,” she says. “Nothing can stop me from reaching my goals.”

Her late parents also felt that the experience strengthened the family’s resilience. Margaret said, “I think from then on we were very strong. I don’t think anything could get us down.”

The kindness shown by Boys Town to relieve their plight made a deep impact.

“We are forever grateful Father Flanagan hired my father to take care of the grounds,” Marilyn says, “because it enabled us to get out of that internment situation.”

She came to view what Flanagan did for her family and others who had been interned as a humanitarian “rescue.”

Then there were the scholastic and life lessons learned.

“A Boys Town education gives you the tools needed to succeed in life,” she says.

Even though discrimination continued after the war, the lessons she learned during the internment and the Boys Town reprieve emboldened her.

“I am grateful that I went through the experience because it made me who I am today,” she adds.

Internees were granted reparations by the U.S. government under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Marilyn received $20,000, and she gave it all away.

She divided the reparations money into equal parts for four recipients: two younger siblings who also grew up in poverty (but did not experience the internment camps of World War II), to create the Fordney Foundation (for helping future generations of ballroom dancers), and Boys Town.

Forty-four years after the Takahashis left their safe haven in Nebraska, Marilyn returned to Boys Town in 1991. During the visit, she made her donation to the place that gave her family a temporary home and renewed faith in mankind.

James Takahashi’s Letter to Father Flanagan

rSoon after arriving at Santa Anita Assembly Center, James Takahashi learned that Father Flanagan was hiring individuals with certain skills to work at Boys Town.

James hand-wrote an appeal to Flanagan asking to be considered. He provided references. The priest wrote Takahashi back requesting more information, including how many were in his family, and checked his references, all of whom spoke highly of “Jimmy,” as he was called, in letters they sent Flanagan.

Here is the text of the original letter James wrote (references excluded):r

Dear Father Flanagan,

Today in camp I heard that you are asking for some Japanese gardeners. I am very interested as I have been a gardener and nurseryman in Los Angeles for the past five years.

Just before the evacuation, I was gardener at St. Mary’s Academy in Los Angeles. I re-landscaped the grounds and put in several lawns.

I am 30 years old of Japanese ancestry but was born and educated in this country. I was converted to the Catholic faith by my wife, who is half Irish and half Japanese.

I studied soil, plants, insect control, and landscape architecture at Los Angeles City College, and am confident that I would be able to handle any gardening problem.

I would be so grateful if you would consider me for this position.

Very sincerely,

James Takahashi

Visit csujad.com for more information about the California State University Japanese-American History Digitization Project.

Visit boystown.org for more information about Boys Town.

This article was printed in the November/December 2018 edition of 60Plus in Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.