Down in the old Chinatown, underground tunnels and hidden rooms were just some of the mysteries reported by The Omaha Daily Bee newspaper in August 1894.

For a former frontier community, Omaha’s media was well-attuned to international dispatches on foreign Chinese news; meanwhile, Bee journalists frequently reported on Omaha’s own domestic Chinese community.

In the Bee’s coverage of the “Sixth Annual Convention” of the Douglas County chapter of the Temperance Union in August 1894, Mrs. D. C. Bryant “reported excellent progress in the missionary work among Omaha’s Chinese.” That same month, as the First Sino-Japanese War broke out between China and Japan over control of Korea, the Bee noted that Chinese forces received support from Koreans everywhere their army went.

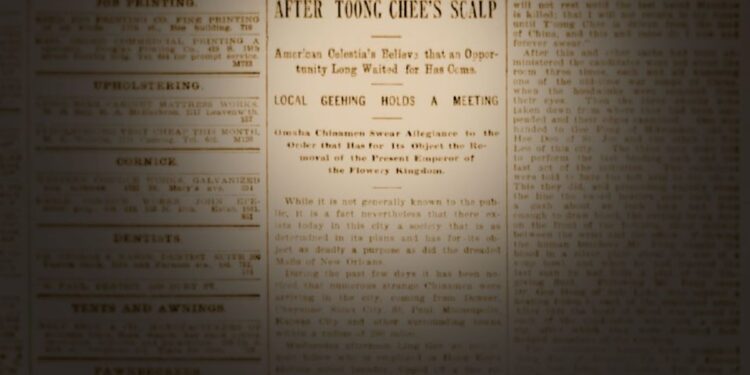

In the Aug. 31, 1894, edition of the Bee, headlines on page-seven declared that the Chinese community’s “Local Geehing” were “After Toong Chee’s Scalp” as “Omaha Chinamen Swear Allegiance to the Order that Has for Its Object the Removal of the Present Emperor of the Flowery Kingdom.”

That would have been Guangxu Emperor, the 11th emperor of the Qing dynasty, whose reign started in 1875 even though Empress Dowager Cixi remained the real ruler of Imperial China. (The name “Toong Chee” likely refers to the reign of the Tongzhi Emperor, who Guangxu succeeded in 1875.)

“Strange Chinamen” had come to Omaha from “Denver, Cheyenne, Sioux City, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Kansas City and other surrounding towns within a radius of 200 miles.”

r

The Bee elaborated that it was “not generally known to the public” but remained “a fact nevertheless that there exists in this city a society that is as determined in its plans and has for its object as deadly a purpose as did the dreaded Mafia of New Orleans.”

Numerous “strange Chinamen” had come to Omaha from “Denver, Cheyenne, Sioux City, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Kansas City and other surrounding towns within a radius of 200 miles.” It was an “intelligent fellow” named Ling Gee who “tipped off” a Bee reporter about what was going to take place. Ling Gee worked at Hong Kee’s Harney Street laundry and told the Bee reporter of a “very important meeting held in the basement of Ging Loo’s laundry” on 10th Street.

The reason so many Chinese were in the city was “that a number of the Omaha Chinese would be initiated into the mysteries of a new society that was about to be organized.” Ling Gee claimed that “even the walls would not divulge any of the secrets which would be told.”

After that one Bee reporter “who speaks Chinese like a native” was sent to Mr. Gee to “complete arrangements for a report of the meeting.” Gee remained hesitant until a “goodly quantity of coin” were shown. He finally said there was potential “to secrete a man in the room where the meeting was to be held, but intimated if the intruder was discovered his chances for again seeing his relatives would not be worth speaking of.”

Naturally, the Bee reporter was “willing to take all of the chances” and just before sunset he “wended his way down” 10th Street and “obeying instructions, knocked at the back door of a small wooden building.” The reporter was “at once admitted by Ling Gee” who led him “down a stairway that was as dark as a sinner’s heart” to “a long, crooked and dark passage for a distance, finally coming into a brilliantly lighted room, fully fifty feet square.”

There, “Mr. Gee conducted The Bee man to a wall that appeared to be as solid as the eternal hills” but “reaching his hand to the height of his head, Mr. Gee pressed upon one of the boards of which the side of the wall was constructed and instantly a section slipped aside, revealing a room eight feet high and some six feet square.” The unnamed reporter described “his prison for several hours” was “elegantly furnished.”

After an hour, he “heard the sound of voices, and a moment later a couple of celestials entered the room and made a tour of inspection, examining chairs, tables, sofas and walls to see that they harbored neither intruders nor spies.” After that, a variety of “strange Chinamen were escorted into the room by Sing Pong” who was a Webster Street “laundryman.” Those escorted in by Sing Pong were introduced as “Ching Chung, Ah Fong, and Tee You,” all of Deadwood, South Dakota. After that there “was a rapid gathering of the clans” as “almond eyed gentlemen” arrived “singly, in pairs, and in quartets until there were fully 150 present” that came from “about every city between the Pacific coast and Chicago, and from St. Paul on the north to St. Louis on the south.”

The unnamed reporter described “his prison for several hours” was “elegantly furnished.”

r

When it seemed the “auditors” were all present, Wo Kung of Omaha, “dressed in a robe of the richest material and ornamented with jewels,” went to the platform to introduce “Hi Ooo Pong of San Francisco, who, he said, would fully explain the object of this meeting.” With that, “Mr. Pong advanced to the platform” while “bowing and scraping” as “the entire audience bowed to the floor.” At a “given signal” they all stood and “remained standing until Fo Lee, the sentry at the door, repeated in Chinese the words, ‘All is well.’’” After that, and “without any ceremony”, Pong “explained that the swords hanging over the chairs were the emblems of secrecy and death, and a rapid death, too, would pursue the man who so far forgot himself as to give to the outside world a word of what was to take place.” After Pong asked “Are you content?” every member of the crowd agreed and he then “invited Joe Fow of Denver, and Wo Tong of Kansas City to the chairs to his right and left.”

Hi Ooo Pong then “said that he had come to Omaha for the purpose of establishing a branch of the Geehing, a society for which had its object the disposition of T’oong Chee, the present emperor of China.” After the Omaha organization they would “elect delegates to the Geehing, which is to be held in Chicago on September 9” where “some plan would be developed.” Pong then went through the history of China as “some centuries ago the Chinese were a law-abiding, peaceful race of people, skilled in the arts, prosperous and happy and well supplied with the goods of this world.” Then came 1643 and the invasion of “the Tartars, better known as the Manchoos” (i.e., Manchurians) bent on “killing the peaceful natives, not even sparing the women and children” as they “burned, sacked, and murdered” their way through Peking and continued their “march of devastation until the sea was reached.” They then returned to Peking and “placed T’oong Chee I upon the Chinese throne” although the war continued until 1649.

Then Pong took “from his pocket a copy of the Wah Tsz Yat Po, published at Hong Kong” and “read extracts” that showed Chinese support to “depose Emperor T’oong Chee, and that for that purpose branches of the Geehing were being organized all over China.” He told the gathered crowd that “now was the time to strike” as the “iron was hot” with the Japanese war and “if the loyal subjects of the land of their birth would throw themselves into the breach, they could attack the armies of the emperor from the rear and give them more than they could handle.” Pong assured them that at next month’s meeting in Chicago they would “adopt heroic measures.” The response was much applause with Pong telling them “the necessity of going down in their pockets and contributing to the fund” that would be “appointed at the Geehing” in Chicago. Pong’s pleas were followed by “short speeches” from “Chung Choo of St. Louis, Kee Woo of St. Paul, and Hee Fow of Sioux City” who all supported Pong’s positions.

The oath continued that they would “swear by the blood of Twang Gee Hong, the first ruler of the empire of China, that I will never rest until every Manchoo is driven off the face of this earth.”

r

It was midnight when Pong asked for any further comment on the proceedings before “he would initiate candidates into the order of the Geehing, he having a special dispensation for the entire territory west of the Mississippi River.” There were 50 people out of the crowd who “arose and expressed a desire to become members, after which they were invited to step to the platform.” With that the “couches and chairs were shoved back to the walls and the wearers of the queue marched to the front, where they were blindfolded by men appointed for the purpose.” After they were blindfolded, the men “repeated the oath” that the Bee reporter loosely translated as “By the bones of Confucius I swear that I will never divulge the workings of the Geehing, and if I do may my body be cut in quarters and be cast to the uttermost parts of the earth, there to rot and to become food for the vultures.” The oath continued that they would “swear by the blood of Twang Gee Hong, the first ruler of the empire of China, that I will never rest until every Manchoo is driven off the face of this earth; that I will kill his first and his last born, sparing neither women nor children; I swear by the blood of Ho Ping Woo, one of our martyred heroes, that I will not rest until the last hated Manchoo is killed; that I will not return to my home until T’oong Chee is driven from the land of China, and this and more do I know forever swear.”

That was followed by other oaths before the “candidates were led about the room three times, each and all humming one of the old-time war songs of China, when the hoodwinks were removed from their eyes.” It was then “the three swords were taken down from where they had been suspended and their edges examined” before they were given to “Gee Fong of Milwaukee, one to Hee Doo of St. Joe, and the other to Yee Lee” of Omaha. Those three were “told to perform the last binding oath and the last act of the initiation” and then “told to bare the left arm to the elbow” and then “proceeding rapidly along the line the sword bearers gave each man a gash about an inch long and deep enough to draw blood, the cutting being done on the front of the forearm, about midway between the wrist and the elbow.”

Pong “caught the blood in a silver plate about the size of a soup bowl” and had “fully a pint” by the end of it all. Then, “Dr. Gee Hong of Salt Lake” came through to administer a “healing lotion to each of the mutilated arms.” The silver bowl of their blood was then passed around as every “took a small sip” before they were “declared full-fledged members of the Geehing.” After the initiation ceremonies, “Ning Fee of Denver, Tol Ye of Kansas City, Lee Lung of Omaha, Tee Gong of Sioux City, and Ah Han of Dubuque” were selected as delegates to the September meeting in Chicago. At last, “as quietly as they had entered the men departed the hall” and the newspaper reporter was finally let go at 3 in the morning.

It remains somewhat of a mystery why Omaha’s Chinese allowed the Bee reporter a glimpse into their otherwise private world. One can only conclude that it was to announce an organized opposition to the Qing dynasty. One could also speculate just how many American newspapers in 1894 had a reporter who was fluent in Chinese. Likewise, the elaborate ruse of the secret room was surely to keep the reporter informed but otherwise well out of the way.

Three months after the Omaha “Geehing” meeting Sun Yat-Sen organized the Revive China Society while in exile in Honolulu, Hawaii. Eighteen years later in 1912, the goal of removing the Qing dynasty was completed. Imperial China came to an end after 2,000 years with the establishment of the Republic of China and Sun Yat-Sen as the country’s first president.

Potential involvement in the creation of the Republic of China by those who attended that August 1894 meeting in Omaha deserves further investigation. The only modern reference to any “Geehing” is the Gee Hing Chinese Company Charitable Trust, established in 1987, that maintains the Tong Wo Tong Chinese cemetery in Kealakekua, Hawaii.

See other Omaha-Chinese content from the March/April 2018 edition of Omaha Magazine:

r

- r

- rAbout the cover of the print magazine

- Editor’s letter: “Year of the Dog”r

- r“Omaha’s Forgotten Chinatown (and the Continuation of Local Chinese Lunar New Year Celebrations)”

- “Chinatown Lost and Found: The On Leong Tong House”

- “Preservation of King Fong Cafe”

- “A Timeline of Chinese in Omaha”

- Video: “Shopping for Chinese Lunar New Year”r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

Ryan Roenfeld is a local author and historian. He is a fifth-generation resident of Mills County, Iowa, and former president of the Historical Society of Pottawattamie County. His most recent book, Wicked Omaha, was published in 2017. Omaha Magazine featured his profile in the May/June 2017 issue.