Keyboarding. Computer skills. Microsoft Office. These classes were required of elementary and middle school students 15-20 years ago. Now, there’s typing in elementary school?

Those courses signify just how rapidly digital technology changes, and consequently, how much digital tech impacts the economy and the education system preparing students for careers.

Current and future professionals face some unique challenges in the workforce because of these rapid changes. A recently published PEW Research Center article revealed that 87 percent of workers believe they’ll need further training and have to learn new job skills to keep up with the dynamic demands of technology. The article indicated that some of the most important assets professionals need include creativity, curiosity, and critical thinking.

Multiple schools—at least three in the last two years—have cropped up in Omaha that are able to address these concerns in a unique way. How do they prepare students for an economic landscape that has changed drastically in the last 30 years and shows no signs of slowing down? Not by being cutting edge, but by playing the long game—employing a classical model of education that’s roughly 2,500 years old.

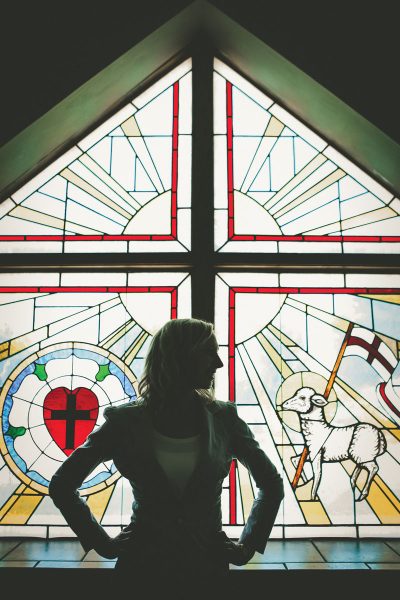

Sara Breetzke, formerly a high school English teacher in Elkhorn, is now the head of school at Trinity Classical Academy, a collaborative, Christian, classical school beginning its second year this fall. Classical education, she explains, is “about teaching kids to enjoy learning and to know how to learn for themselves.”

Classical schooling is made up of three distinct stages of learning that mirror the development of a child. It’s known as the “trivium.” The grammar stage (first through fourth grades), when children are considered “information sponges,” involves memorizing facts and information; the logic stage (fifth through eighth grades), when kids are consumed with “why?”, involves organizing those learned facts in logical ways; the rhetoric stage (ninth through 12th grades), when adolescents want to express themselves, involves critical thinking and persuasion.

Brandon Harvey, newly-appointed headmaster of the two-year-old Chesterton Academy, highlights the importance of the “unity between the content and the method” for learning well. “The goal,” he says, “is that [students] encounter truth, goodness, and beauty.”

Another distinction is the focus on virtue as a fundamental feature of education. A primary goal of the classical education is to create, in Harvey’s terms, “[People] of virtue [who] strive to not just know the truth but to imitate goodness.”

Trinity Classical Academy and Chesterton Academy are Christian schools, though the classical education method began in ancient Greece and Rome and need not necessarily be Christian. Through a variety of sources, classical schooling immerses students at a very early age in great works—from Aristotle to Augustine, Charlotte Bronte to Dorothy Day, Frederick Douglass to Charles Darwin.

Breetzke succinctly summarizes the philosophy behind immersion: “You can’t be creative until you’ve seen people be creative.” While rewarding, this is an extended endeavor—a pilgrimage of learning.

Whereas prevailing models of education assume content should be engaging and fun for students now, and tends toward mass production by teaching to a test, classical schooling assumes content will be engaging and fun once students are good learners, and tends towards character development. So, says Breetzke, “You’re not going to see much standardized testing.”

When it comes to tests like the SAT and ACT, Harvey explains, “Classical schools don’t really focus on standardized tests, and in doing so they actually surpass most other schools [in test scores].” Student success is due in part because the curriculum for each course intentionally integrates with others. Subjects are not treated like cities on a map, unique yet connected. The facts of science relate to the events of history, which are linked to the literature of the time. This method creates curious, critical thinkers. Therefore, Harvey points out, “Classical education is not just for the intellectual elite.”

So how does the classical model prepare students for a tech-heavy business world? By changing that very question. The goal isn’t to prepare students for a type of economy (technological or otherwise), but to create virtuous humans who know how to learn and can take responsibility for themselves and the world around them. Breetzke explains: “Career prep looks different. It’s not skills. It’s character…Skills are much more easily learned than character…We are giving kids resources and riches to draw on that can reinvigorate a tech-heavy business world.”

The wisdom instilled by the millennia-old trivium prepares students for the ever-changing digital-tech economy. Through it, students become people who can discern truth, imitate goodness, and enjoy beauty. While not the skills-based learning most people are used to, classical education instills qualities that a digital economy still needs.

rThis article was printed in the Fall 2017 edition of Family Guide.