Kelly Hill stands on the corner of 30th and Lake streets admiring Salem Baptist Church’s towering cross, which looms over the landscape. A member of the church for more than 15 years, Kelly grew up in the now-demolished Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects not far from the area. He can remember a time before Salem sat atop the hill, when the Hilltop Homes housing projects occupied the area.

“I left Omaha to join the military in 1975, and I didn’t return until 1995. I missed all of the gangs and bad stuff in Hilltop,” Hill remembers. “When I was a kid, it wasn’t a bad area at all. Me and my sister would play around there all the time.”

Within those 20 years, Hill was fortunate to have missed Hilltop’s downfall, as it would eventually become one of Omaha’s most notorious housing projects.

A major blight on North Omaha’s image in the 1980s to mid-1990s, Hilltop Homes would eventually be the second major housing project demolished in the metro area after Logan Fontenelle.

Before Hilltop Home’s razing in 1995—which had the unfortunate consequence of displacing many lower-income minority residents—the plague of drugs, murders, and gang activity had turned the area’s housing projects into a localized war zone.

It was a far cry from their humble beginnings as proud housing tenements for Omaha’s burgeoning minority population that exploded in the 1940s.

Built around Omaha’s oldest pioneer resting place, the neighborhood takes its name from Prospect Hill Cemetery on 32nd and Parker streets. Prospect Place was repurposed by the U.S. government to house a large influx of minority and low-income residents, mostly African-Americans, who migrated to Omaha seeking opportunities outside the oppressive South during the mid-20th century. Some 700 units of public housing emerged across the city in the 1940s, including Hilltop Homes and the nearby Pleasantview Apartments.

The projects were conveniently situated. Hilltop’s 225 units were positioned in a centralized location along 30th and Lake streets, near the factory and meatpacking plants on 16th Street to the east, with Omaha Technical High School to the south (the largest high school west of Chicago at the time).

Multiple generations of families would come to call Hilltop and Pleasantview their first homes; however, the collapse of the job structure on the north side of Omaha in the late 1960s would be a major catalyst in Prospect Place’s eventual downfall.

Successful factories and stores that kept the area afloat—such as The Storz Brewery and Safeway Grocery Store—closed their doors. At the same time, new civil rights laws prohibiting job discrimination were being passed. Some believe that fear of change, and fear of civil rights era legislations, motivated major employers in the community to move from northeast Omaha westward. A disappointing trend of joblessness and poverty would eventually devolve the community into a powder keg ready to blow.

Multiple riots at the tail end of the 1960s would take an additional toll on North Omaha. Four instances of civil unrest would erupt from 1966 to 1969, decimating the community.r

“Too many kids were getting shot, killed, it was pretty bad in Hilltop.” Benson says.

rThe last North Omaha riot would happen a day after Vivian Strong was shot and killed by Omaha police in the Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects not far from Prospect Place. Rioters would go on to fire-bomb and destroy a multitude of businesses and storefronts in the neighborhood.

The local chapter of the Omaha Black Panthers would stand guard outside of black-owned businesses like the Omaha Star building at 24th and Lake streets in order to prevent its destruction. Many businesses would never recover from the millions of dollars in damages caused by the riots.

These disturbances would mark an important time-frame for Hilltop and Pleasantview’s gradual downfall. The turbulence within the community, spearheaded by systematic racism and poverty would take its toll on the area.

The Prospect Place projects would devolve into a dilapidated ghetto, with even harsher times awaiting the neighborhood as gangs and crack-cocaine would hit the city hard in the 1980s.

Omaha wasn’t a place people would have thought the gangs of Los Angeles, California, would make a strong showing. Quite the contrary, gang members from the West Coast would eventually discover Omaha’s smaller urban landscape to be an untouched and lucrative territory.

Ex-gang member Edwin Benson can remember the switch taking hold in his later teenage years.

“The Crips came first, I’d say around the mid-to-late 1980s. They took over areas like 40th Avenue and Hilltop,” Benson says. “The Bloods’ territory was further east, big in the Logan Fontenelle projects and up and down 16th Street. So, gang-banging kind of took over the city for a long while.”

The isolated, maze-like structure of Hilltop and Pleasantview, along with the high-rise apartments added in the 1960s by the Omaha Housing Authority, would make them ideal locations for the burgeoning Hilltop Crips and other smaller street gangs.

“I can remember kids from Hilltop coming over to Pleasantview and starting trouble.” Benson recalls. “We would fight about who had the better projects! We fought with our fists, rocks, sticks…whatever was close you got hit with!”

A refuge for illicit activity had sprung to life within Prospect Place in the 1980s. Members of the community, as well as police officers, grew hesitant to venture into the area. Hilltop became a forgotten segment of the city, lost to the surrounding metro’s progress, marred by a decade of violent crime and drug offenses.

Hilltop would see an unfortunate trend of senseless homicides and gun violence that would peak in the early ’90s.

In 1990, two young men from Sioux City were shot outside of Hilltop when they stopped to ask for directions to the Omaha Civic Auditorium on their way to an MC Hammer concert.

In 1991, a 14-year-old boy was arrested for stabbing a 13-year-old boy during a fight. That same year, a local Crip gang member was gunned down at the 7-Eleven on 30th and Lake across the street from Hilltop.

In 1993, the pointless murder of another teenager may have finally spelled Hilltop’s doom. 14-year-old Charezetta Swiney—known as “Chucky” to friends and family—was shot in the head from point-blank range over a parking space dispute on Oct. 22. A sad occasion at the beginning of the school year, Benson High School was gracious enough to host the high school freshman’s funeral with more than 700 people in attendance. She was the 31st person slain in Omaha that year.

Jay W. Green, 27, would eventually be found guilty of Swiney’s homicide, charged with second-degree murder and use of a firearm to commit a felony in the summer of 1994. At the end of that same year, Omaha’s City Council would begin laying the groundwork for Hilltop Homes’ eventual razing in 1995.

Benson, the former gang member, believes Swiney’s murder and the rampant gang activity within Prospect Place were the main reasons for Hilltop Homes’ demolition.

“Too many kids were getting shot, killed, it was pretty bad in Hilltop.” Benson says. “Once the projects were gone, I think the Hilltop Crips just kind of faded out. We would joke and call them the ‘Scatter-site Crips’ since everyone was being moved to the scatter-site housing out west! If you hear someone claiming Hilltop these days they are living in the past.”

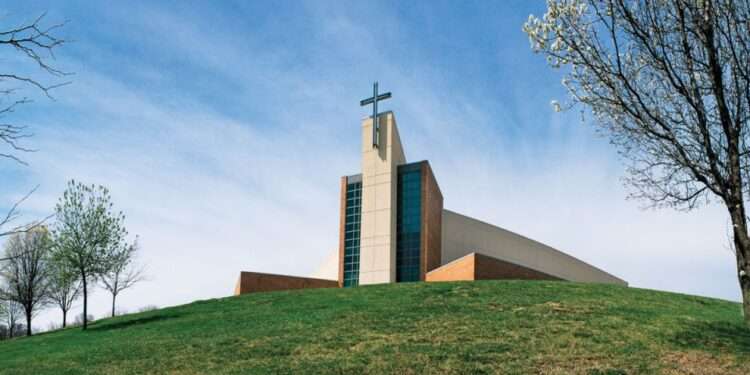

The demolition would leave a desolate space in its wake. Fortunately, the barren eyesore would not last long, as Salem Baptist Church would make their ambitious proposal for the site in 1996.

“I can remember me and my sister marching from the old church grounds on 3336 Lake St. to the new site on the hilltop,” Hill says, reminiscing with vivid recollection of April 19, 1998, the church’s groundbreaking. It was a glorious Sunday for church members, led by then-senior pastor Maurice Watson, a culmination of Salem’s proposed “Vision to Victory.”

Salem’s groundbreaking ceremony was heralded, marking the once-troubled land of Prospect Place as an “oasis of hope.” The community witnessed the progress as the newly razed 18 acres of land transformed from a vestige of poverty into a church sanctuary seating 1,300 people, in addition to classrooms, a multi-purpose fellowship hall, a nursery, and ample parking. Prospect Place was undergoing a new renaissance which would continue well into the new millennium.

Othello Meadows is the newest pioneer at the head of changing the image of Prospect Place. Having grown up on Omaha’s north side, Meadows remembers the projects as “a place not to linger if you weren’t from there.” After years away from his hometown, seeing the remnants of Hilltop Homes and Pleasantview Apartments was eye-opening.

“When I came back to Omaha, I was surprised by the disinvestment in the area after the projects were gone,” he says. “It went from housing thousands of people, to a sense of abandonment; like, only two houses were occupied on the entire block.”

Meadows’ words ring true. Other than Salem’s deal with Walgreens, which acquired acres of land for around $450,000, no additional development had taken place for years within Prospect Place. Fortunately, Meadows and the 75 North Revitalization Corp. are looking to reinvigorate the area.

As the executive director of 75 North, Meadows refers to Prospect Place as the “Highlander” area, which helps to separate the land from its troubled past. His goal is to bring life back to the area.

The development company now owns the land where the Pleasantview apartments resided before being demolished in 2008. A plan for a new neighborhood with continued growth is the main focus for the area, and he expects tangible progress in the coming months.

“If you drive down 30th Street between Parker and Blondo, you’ll see real work happening and real things going on.” Meadows says. “We have about 12 buildings under construction that are 50-70 percent complete [as of early February 2017], including a community enrichment center called the Accelerator that is 65,000 square feet, a very beautiful building. By late April to early May 2017 we should have some apartments up, and we already have people putting down deposits and signing leases. People are excited to be moving into the neighborhood.”

When asked about the targeted clientele for the new apartments and retail space, Meadows provides a broad answer: “The motto that we follow is—trying to create a mixed-income community. We’re not trying to recreate the projects, of course, but we also don’t want to create a neighborhood where longtime residents can’t afford to live. We have to balance the prospects of affordability and aspirational thinking.”

Indeed, when looking at the seventyfivenorth.org website, the ambitious vision for the Highlander Apartments is a far cry from the projects. Photo galleries and floor plans envision a renewed community akin to Midtown Crossing and Aksarben Village. The images are cheerful, depicting people riding bikes and walking dogs, even an imagined coffee shop.

In a way, the renewed development, optimism, and potential for economic growth in the Highlander area can trace its roots back to the members of Salem and their desire to build a signal of hope where it once was lost.

But Hill (the former Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects resident who left Omaha in 1975 and returned in 1995) doesn’t think the church is given adequate recognition for its contributions.

“If a person didn’t know this place’s history of violence and poverty before Salem was built, they would only see the progress in this area as simple land development,” Hill says. “Salem doesn’t tend to broadcast the things they do for the area other than to its members, so those on the outside don’t necessarily recognize its lasting influence.”

It’s undeniable that the soaring church spire on the hill is a spectacle to behold on a bright, sunny day. It stands as a symbol of hope and belief. Benson still looks at the former site of Prospect Place with a hint of longing.

“I know it might sound crazy, but I was a little sad when Hilltop was torn down.” he admits. “A lot of good memories were made in those projects. But I love seeing the church up there. I hope whatever comes next is good for the community.”

Visit salembc.org for more information about Salem Baptist Church. Visit seventyfivenorth.org for more information about 75 North.