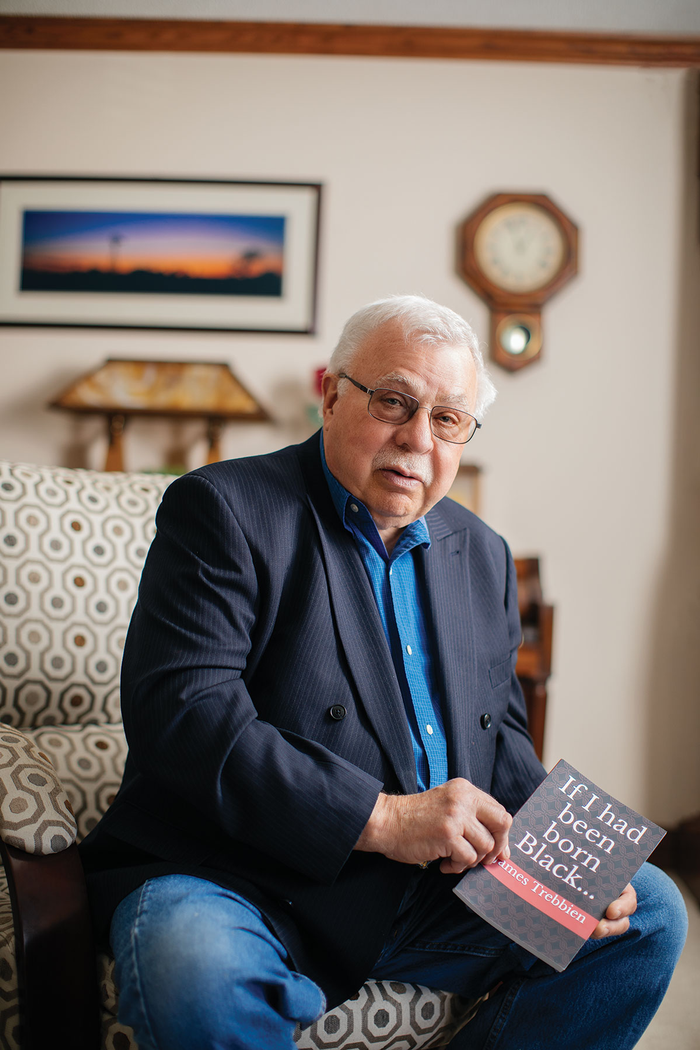

Jim Trebbien has opened a door he can’t close.

br

The retired chef and chef instructor is now the author of several books. His most provocative works contain stories he collected from people going through a thing he can’t fathom: being Black in America.

br

These tales have given the 70-plus-year-old writer a different outlook on privilege.

br

“People come up with a lot of reasons to blame a lot of people, but the truth is, in this society, Black people have never had a fair chance as a group,” Trebbien said.

br

Trebbien’s three books are titled It’s a White Life, Journey to Understanding Race in America, and It’s Black and White. Within them, he contrasts situations and circumstances that have happened to friends and colleagues identifying as Black with his own as a white man.

br

It’s an interesting concept.

br

It shouldn’t feel so unique to hear a self-proclaimed ‘conservative kind of guy,’ who referenced overspending liberals and what makes America great, passionately acknowledge Black Americans’ historically unfair position in America.

br

“Most of my conservative friends say, ‘Well Jim, people ought not to do anything wrong and they’d be fine,’” Trebbien said. “If nothing else, why is this happening? If all these Black people are guilty, why is it happening? Why do more Black people have to commit crimes? Something is driving this.”

br

Trebbien admits he wasn’t always mindful of racial issues growing up a mile south of Lake Okoboji in Milford, Iowa. Attending Catholic school and working on the family farm kept him far away from the tribulations happening further south and in the big cities.

br

It wasn’t until after Trebbien was drafted into the Army in September 1969 that he witnessed his most memorable account of bigotry. After completing basic training, a simple gesture like letting a fellow Black soldier sit on his bed in the barracks earned him scorn from a white soldier.

br

“I noticed a white kid that I later learned was from Tennessee jump up and stare with a scowl on his face. After the Black guy left the room the white kid said, ‘Man, what the hell you doing? You let that kid sit on your bed. Where I come from we don’t let Black people sit on our beds,’” Trebbien remembered.

br

This blatant display of racism stuck with Trebbien throughout his life. He had seen a small example of the intolerance some people had for Black Americans. It was uncomfortable and unfair.

br

“I had never thought of that. I wasn’t brought up to be a racist. I wasn’t aware of these problems,” he said.

br

Treating people with respect, kindness, and dignity is something Trebbien always strived to accomplish. It came in handy during his stint as dean of the Culinary Arts program at Metro Community College’s Fort Omaha campus in the mid-1980s.

br

The college’s location in the heart of North Omaha—which, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, accommodated nearly 70% of Omaha’s Black population in the 1980s—gave him relationships with myriad people across the racial spectrum. Trebbien’s position kept him mindful of issues regarding diversity and race, but his cognizance didn’t necessarily lead to action.

br

“Being aware doesn’t mean I don’t have feelings for people that didn’t have certain opportunities,” he said.

br

His duties as a mentor eventually led to a remarkable meeting with a new mentee Trebbien met on a cold, windy January day. While having lunch at the campus with his understudy—a younger Black man named Cameron—Trebbien asked his new acquaintance about his life and got more than he expected.

br

“I think he wanted to tell this older white man that sipped tea in the afternoon about his life,” Trebbien recalled.

Cameron told his new mentor about his loving mother who cried when she was forced to move her family from their home to the downtrodden projects after separating from his father.

The new neighborhood was unsafe for a young boy.

Cameron told Trebbien how an innocent game of cops-and-robbers with friends devolved into chaos when a man came running from an apartment pursued by another man shooting a real gun. Cameron and his friends hid behind cars during the shootout.

Trebbien was enthralled by Cameron’s tales. They found themselves standing behind a building in the frigid conditions as Cameron continued telling accounts of his past.

“When I heard gunshots at home, I knew my dad or grandpa were out hunting. When Cameron heard gunshots he ran and hid,” Trebbien said.

Some stories truly hit home, and after meeting with Cameron a number of times, Trebbien approached his mentee with the idea to tell his story in a book.

“I was fascinated, not only by all the crap he’d been through, but [that] I had done a lot of things he had done, only worse,” Trebbien said, recalling a domestic incident with his former wife that mirrored one of Cameron’s encounters. Except Cameron ended up in jail while Trebbien stayed home.

“Police came to the house, asked me a couple of questions and left. Never followed through,” Trebbien remembered. It made him feel like he had some kind of unfair advantage over his mentee.

“It’s like, oh well, straighten up and don’t do anything wrong and the police won’t come by,” Trebbien said. “But, Cameron was a good guy not doing anything terribly wrong that had to put up with a lot of crap in his life.”

Unfortunately, Cameron refused to co-author or fully lend his likeness to the book, hence the absence of his last name throughout this article.

Former gang ties and a strong desire to separate his family from his past life made Cameron stay far away from those stories from another lifetime.

Trebbien decided to interview other Black people he knew about their life experiences for his book.

One account told by his former secretary involved her successful brother, who owned a house in a predominantly white area in West Omaha. He was stopped numerous times in his neighborhood by police officers wanting to check his registration—to the point it became embarrassing.

This harassment by law enforcement became a disturbing trend in Trebbien’s documents. In the past, he may have chalked up these run-ins with the police as normal events. Those things happen to people, move along.

An occurrence with Cameron after a lunch at McDonald’s, however, broadened his perception.

Following their meal, Trebbien offered to give his mentee a ride to Crossroads Mall. Heading south on 72nd Street in Trebbien’s Ford truck, he remembers going about 10 miles per hour over the speed limit—as was the surrounding traffic—when they noticed a police car heading north.

“Oh man, you’re going to get pulled over in a minute. Wait and see,’” he recalled Cameron saying.

Two blocks from Crossroads they saw the flashing red lights of the police car behind them. Trebbien couldn’t believe it. Why would the officer stop him amongst a host of other cars speeding alongside?

“How’d you know they were going to stop me?” he asked Cameron.

“Think about it Jim, here you are, older white guy with a young Black guy in the car. What do you think they think? Maybe we are up to a little mischief. You were stopped for being a white guy with a Black guy.”

Trebbien took his mentee’s accurate prediction seriously. When the officer came to the door Trebbien couldn’t help but ask why he was stopped.

“You were speeding back there,” the officer said. Trebbien refused to believe that reason and felt defiant.

“Oh, OK,” he said. “Since you’re stopping me for speeding, I’m two blocks from dropping this young man off. He’s going to get out of the car in just a second.”

The officer tensed before ordering Trebbien, “Sit where you are. Both of you.”

Despite Cameron’s attempts to calm him down, Trebbien pressed on.

“No, wait a minute. You told me you’re stopping me for speeding,” he said. “That’s not an offense this guy could have been involved in. He’s two blocks from where he needs to go and he needs to get there. So you give me my ticket for speeding, but he gets out of the car and goes!”

The officer wasn’t prepared for such a challenge. He stood by the door, silent.

“Just get out of the car,” Trebbien told his mentee. He watched Cameron slowly exit the car with his hands clearly in view before quickly walking down 72nd Street towards the mall.

Later Cameron told Trebbien he was becoming aware of how things really are.

“I’d have thought in the past, why don’t people just listen to what the police officer says and do it,” Trebbien said. “[This time] I kept thinking if that was my youngest son and I said my son is going to walk down the street, he would have said go. I don’t know that for a fact, but my past experiences in life lead me to believe that.”

These days Trebbien doesn’t have much contact with Cameron, but his young mentee’s influence was prevalent. Trebbien’s resolve to openly discuss issues about race continues to parallel a strong desire to see Black Americans treated fairly in the country he loves.

“My testimony about race opened my eyes,” he said. “There are lot of white people that came to America from around the world and worked their butts off here…and got ahead. But I toured a plantation two times and looked at how slaves lived and heard people tell stories of what slavery involved. I think they had to work as hard as, or harder than, any other immigrant and got nothing out of the deal.”

Trebbien’s books can be purchased from Amazon.

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Photo by Bill Sitzmann