C. Scott Fields walks steadily around their Dundee duplex, a tricolor corgi named Avocado on their heels. Fields wears a Blue Line Coffee crewneck sweatshirt; old wooden floorboards in their living room give. Incense burns, a silver tinsel Christmas tree remains in the corner of the space, and Fields swoops auburn bangs out of their eyes.

They are comfortable; they are relaxed; they are at home.

It’s hard to believe that in another life (a pre-pandemic one), Fields was a world traveler, attached to nothing but a camera strap.

Fields visited Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, Colombia, Canada, and Jamaica; all far-fetched places for that pair of Council Bluffs-grown feet to land.

“I started traveling around the time Instagram got big and everyone wanted to see the world and get the coolest shots,” Fields said. “But historical books and magazines, seeing beautiful photos of southeast Asia, photojournalism is what shaped the way I approached travel photography. My goal was to see how long I could sustain myself with my camera and a singular backpack full of things.”

Fields’ first travel experience, however, was as cookie-cutter as could be; a resort in Jamaica. At first, it was fun. Then, a new feeling arose.

“I realized I was missing out on the community,” Fields said. “It was a slap in the face to go to the edge of this resort and see a fence that people couldn’t enter. I felt like there was more beyond it, and I felt passive being there. I wanted to know about the people who worked in the hotel, who they were and what they did when they clocked out. Like, who are you beyond this resort?”

The gears were set in motion.

In the beginning, there was little rhyme or reason to the travels. Soon, though, Fields followed their Omaha network around the world. An Omaha social media connection led to photographing a traditional Vietnamese wedding in Đà Nang and Ho Chi Minh City.

Later, an invitation from friend Nicole Malene brought the two of them to Costa Rica, where they followed and photographed a troupe of acrobats and performers on a weeklong teaching and learning excursion.

“I was placed in a situation where people opened up to me without any hesitation and let me stick a camera in their face,” Fields recalled. “At the end, the whole troupe of, like, 80 people rushed around me and hugged me. I snapped photos in that moment, blurry smiles of people enveloping me, and I went back to my tent and just wept. It was a ‘click’ moment where I realized I was in the right place.”

Fields grew up in a predominately white city and attended Catholic school, but perceptibly learns best outside of a classroom—thrown into the world with a first-hand account of it all.

“I dropped out of college to go on a 16-day trip with a couple other photographers,” Fields said. “I don’t know how else I’m going to learn. It was a way for me to expand my worldview, to learn what it was like to be vulnerable, to see other people’s faces, and count on the kindness of strangers. Travel is incredibly humbling and teaches you a lot about how to shut up and listen.”

Part of Fields’ desire to leave the Midwest was that of being a stranger, to observe, and to “get out of the way.” Fields, however, describes their photographic style as a kind of conversation, up close and personal and the subject, rolling with the punches.

This is the nuance of Fields’ work; existing in the background in such a way that allows another human to feel so comfortable that a connection is natural and immediate. It’s as if viewing the world as an art gallery of humanity, and Fields’ job is to sit on a bench until they understand the person.

Fields’ friend and fellow photographer Michael Hennings is another voracious traveler—and an avid admirer of Fields’ work.

“Their style is a duality between intimate and pedestrian,” Hennings said. “When I see their travel work, I see it as a form of falling in love and appreciating the nuance of each individual place as if it was a person. When you consider the color palette, the way they compose, the way they work with talent, the textures, and the subject matter, their work, as a whole, feels like a mood board for something bigger. It’s expressing the larger story of who they are and what they hold dear in life.”

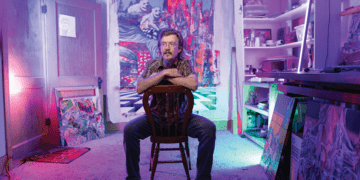

These days, Fields has been leaning more into what it means to be an artist over what it means to be a traveler, considering what the next iteration of a photography career looks like, perhaps holding space in a gallery or producing printed work.

“For a long time, I [was] like a hacky sack. Wherever I was kicked, I went,” Fields said. “People were incredibly gracious to me, and I am grateful that anyone gave me the opportunity to take their portrait. Figuring out this new phase, it’s intentional and slow. I’m trying to find appreciation from where I came from, rather than escaping it.”

Visit carleyscottfields.com for more information.

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.