When Dr. Jack Lewis received the call, it was almost midnight.

Elvis Presley needed his ingrown toenail dug out.

“I think he just wanted drugs for his sore toe,” Lewis recalls, pounding the table and laughing.

Lewis turned him down. Not so surprising, Lewis says, considering he is an internal medical specialist so typically does not clean out toenails.

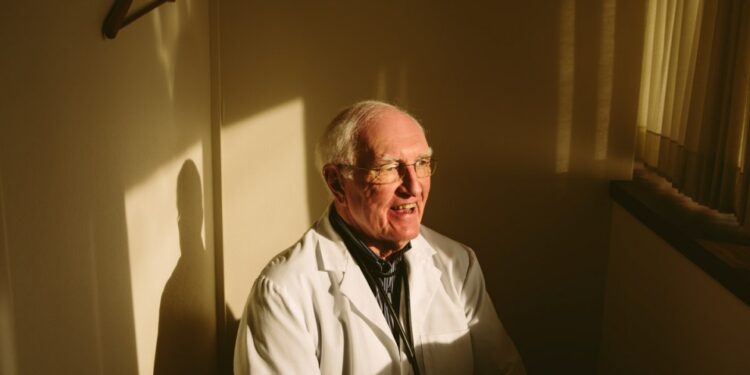

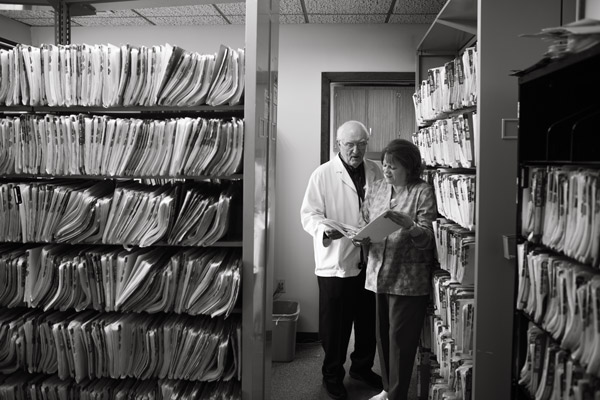

“Although I did do one today,” he says, smiling at his nurse of 32 years, Betty Wesch. He is relaxed, casual in his plaid shirt, brown slacks, and suede shoes.

When the Beach Boys needed a vitamin B12 shot before going on stage, Lewis sent his “girls” instead. After his nurse administered the shot into the butt cheek of one band member, she promptly fainted.

Why didn’t Lewis go instead?

It was the middle the day. His patients needed him.

Lewis is a little reminiscent of a rural doctor, one deeply rooted in the community. He is the chairman for the University of Omaha’s Maverick’s Club. He is the president of the Omaha Police Foundation. He has served on countless boards.

Lewis has just turned 80.

“His stamina is amazing,” Wesch says.

He has no plans to make a Bucket List since he has done everything he has wanted to do.

Memories and accomplishments are scattered along his walls collecting dust.

One photo shows a muscular Lewis on a wooden chair doing a somewhat impossible stunt on a ski. There is another of him in an old leather helmet during his time at Stanford as a reserve quarterback.rLewis also quarterbacked at Omaha Central High School. He has left his legacy as the team physician for the past 50 years, a role he took over from his father.

Jay Ball, the head football coach at Central and a former player, considers Lewis a positive force on the sidelines.

“He would often allow various players to see him (often free of charge) for athletic related ailments (including myself).” Ball says. “Our players and coaches all appreciate and respect the work he has done for CHS. We are definitely going to miss him.”

After 500 Friday night football games and 20,000 free physicals, Lewis will hang up his stethoscope this spring.

His wife of 55 years, Kathy, says it is time to “back off.”

“It’s too cold and hard,” he adds. He has treated some famous athletes like Ahman Green and Calvin Jones. He recalls late nights such as a game against Millard South which went into seven overtimes and kept his wife waiting for hours. And there were some football disasters.

Late in the fourth quarter during a rainy game, Lewis thought a Central player had broken his neck. He could not move. Lewis supported his legs and arms and duct-taped him to a stretcher with the help of others. Lewis immediately called in a med-chopper.

“How am I going to X-ray his neck?” the technician asked at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

“Here, I’ll help,” the player said as he crawled off the table and walked over to his coach.

Lewis said the player suffered from hysteria and was scared to death, believing he was really paralyzed.

He had to kick the player off the team. “I have control … no one plays without my say so,” Lewis says brusquely.

His son John, who is in practice with him as a physician’s assistant, lives in Elkhorn so cannot make the drive to take over on the sidelines as his father and grandfather had done for so many years.rThe Lewis line at Central is over.

Lewis says most doctors won’t want to take his place; liability on concussions is just too tough.rAs the fight doctor for the Golden Gloves for the past 50 years, Lewis has seen his share of action.

He was ringside at the heavyweight fight between Joe Frazier and Ron Stander at the Civic Auditorium in 1972. He gave both fighters physicals beforehand, and says Frazier had a low IQ and could not read or write.

A known bleeder, Stander had signed a contract saying no one could stop the fight but Lewis. Lewis noticed Stander was swinging at his tennis shoes at the end of the fourth round.

“Doc, where are you?” Stander asked.

“I’m over here,” he said. Lewis took Stander’s head in his hands. A huge gash gushed out of his forehead possibly from a head butt. Stander couldn’t see anything because blood ran into his eyes.

“I’m going to stop the fight now,” Lewis said.

“No …No ..I’m fine,” Stander said.

Lewis made the call to stop the fight, giving a now black and blue Stander around 17 stitches.rStander was angry with Lewis at first, but later thanked him for saving his life.

Saving lives is something Lewis feels good about, the reason his feet hit the floor every morning at a superstitious 5:44. There are people up at the hospital “sick as hell.” He then chats with his former partner Dr. Sam Watson every morning for an iced tea at Village Inn.

Lewis doesn’t eat breakfast. He is extremely adamant he’ll never fly in a plane again. Unlike most doctors, Lewis has never had a cup of coffee, drank a martini, or swung a golf club.

“They (other doctors) think I’m crazy,” he says with a laugh since most of his associates golf.

He has been at his private practice for 50 years and has no plans to retire. Although Lewis has started to do some electronic work, he still relies on the old chart and file method.

“I spend time … and learn a lot by looking in patients’ eyes,” Lewis says. “I don’t sit around and type.”

Lewis can be stern and gruff, but is extremely kind to his staff which includes buying them lunches at times.

“He also gives us (nurses) his football tickets down in Lincoln when he doesn’t go and his UNO hockey tickets,” Wesch says.

After graduating from the University of Nebraska Medical Center, he joined his father Raymond in the family medical practice. Lewis says Raymond was a “great guy” and he hoped he’d have at least five years together; instead they had twenty-five. His father retired at 83 and died of lung cancer soon after.

Many generations have stepped through the door of the office, including patients his father delivered. Lewis has ten patients over 100 years of age, including one lady who is 108 and still drives to the office.

“She’s alert as hell,” he says. “She used to play bridge with my dad.”

Lewis keeps track of his families which includes driving about 100 miles on Sundays to visit nine nursing homes.

His advice to the younger generation is surprising: don’t be a doctor.

“They are not going to make good money,” Lewis believes. Most are just too far in debt after college and doctors just don’t make nearly as much as they used to due to insurance.

Lewis says he never looks ahead, but hopes to continue caring for his “really good friends.”