Author, speaker, professor.

President and CEO of the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum.

Astronaut.

These are titles a young boy growing up in 1960s Ashland, Nebraska, hardly could have envisioned as his life’s trajectory.

But they are everything that Clayton “Clay” Anderson ended up becoming—and more.

As a child, the bright, ever inquisitive boy often went adventuring to Crystal Creek, climbing a nearby hill to enjoy its high vantage point overlooking the Platte River Valley. He could also see a long way from atop that rise via a backyard telescope aimed at the winking constellations millions of light years beyond Ashland.

America’s space program was at its peak during this era, dubbed the “Space Race,” during which the United States and the Soviet Union competed to establish supremacy among the stars. Young Clay told anyone who would listen he was destined to be an astronaut.

Anderson made good on that promise, but he bucked long odds in becoming the state’s first—and still only—person to claim that job title. After living that dream far away from home, he assumed a new role as director of the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum, an organization nestled atop that same overlook he frequented in his childhood. To him, this unlikely progression of events is more than coincidence.

It’s written in the stars.

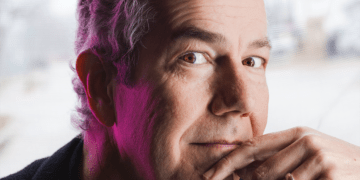

“I think the longer I’m here, the more I feel I’m supposed to be here,” the 65-year-old reflected on his orbit from Nebraska beyond the Earth’s atmosphere and back again.

He appreciates the people who made it possible to become a “star sailor” (the literal translation of the Latin-based “astronaut”). Without them, he is quick to recognize he would never have experienced light years, zero gravity, and G-force. Anderson is especially grateful to his mother and father, Alice and John, a school speech pathologist and state department of roads worker, respectively.

“My parents were very good at knowing when history was being made and putting their kids in front of the TV for those historical world events,” Anderson explained.

One of those televised events was the famed Apollo 8 spacecraft, the first crewed spaceflight of astronauts to leave the Earth’s atmosphere and reach the Moon, orbiting it eight times before returning to terra firma.

That historic moment was particularly vivid for Anderson, just 9 years old at the time.

“The key one for me was Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve in ’68 [and] watching the manned capsule go by the Moon for the first time,” he shared. “I was pretty fascinated by that.”

A little over a year and a half later, he sat enthralled when on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 became the first spaceflight to land humans on the surface of the Moon, courtesy of the lunar module. He watched as Neil Armstrong proclaimed one of history’s most famous and instantly recognizable quotes: “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

He also anxiously followed as an in-flight crisis scuttled Apollo 13’s 1970 Moon mission and forced a harrowing, improvised return to Earth.

A budding Renaissance man, Anderson’s intellectual curiosity was matched by his passion for sports. After graduating Ashland High School, the competitive athlete and academically-driven student attended Hastings College. There, he studied physics and participated in football, basketball, and track, earning his Bachelor of Science in 1981.

When Maynard Ray Huntley, a NASA employee, native Nebraskan, and Hastings alumnus, visited his alma mater, a counselor familiar with Anderson’s interest in space made sure the two met. Encouraged to apply to NASA’s summer internship program, Anderson took his own first step before making the ultimate leap.

“That [the internship] allowed me to go down to Houston in 1981 to work for a summer at the Johnson Space Center,” he said. The time was also an adventure in another respect; while there, he met his wife, Susan Jane Harreld. They have a son, Clayton “Cole,” and a daughter, Sutton Marie, together.

“How fortuitous—I’m a believer in God,” he shared. “I think He puts things in a place for you to find them, but you have to do what’s required to achieve them. If a door opens, you have to be smart enough to realize that and step through the door. Had that door not opened, who knows? I probably would have ended up coaching high school basketball or something. I just don’t know.”

Anderson credits his Nebraska roots for helping to take those steps toward the celestial journey he’s certain he would never have made otherwise.

“The way I was raised in my small town community by my church, my family, my coaches, my teachers—they all helped shape me to be the person that was good enough to get that internship,” he said. “After that, it was kind of on me.”

The NASA internship spurred Anderson to earn his Master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering at Iowa State University in 1983. The degree became his path to working in the space program, where, as a NASA engineer, he famously applied 14 times before succeeding on his 15th in June 1998. As he likes to quip: “It’s easy to apply to be an astronaut—and very difficult to be selected.”

Anderson launched aboard the Shuttle Atlantis as a mission specialist in June 2008 to become a member of the Expedition 15 and 16 crews, spending 152 days on the International Space Station in 2007. He returned to Earth aboard Discovery in November. He was a mission specialist on STS-131 in 2010.

He made the most of his time among the stars. Knowing he would see Ashland from 240 miles above, Anderson calibrated sophisticated photographic equipment to capture the panorama of the blue planet beneath him. When the moment came, however, he was too overwhelmed to activate the cameras.

“I cried,” he shared. “No pictures were taken that time…There I was flying over my home where the people I know and love and who raised me live. I was in space above them. It just kind of tugged at my heart. It was one of the most emotional experiences of my entire time in space.”

The veteran astronaut eventually logged 167 days total among the stars, completed six spacewalks, and became known for stunning, other-worldly selfies, trivia contests he played with ground control, and songs he shared with ground control and specific individuals. One such memorable tune was Bryan Adams’ “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You” played from space for Susan Jane’s birthday.

As one of fewer than 1,000 humans to go into space, Anderson’s orbital perspective is rare, and he describes his stellar adventure with awed eloquence. “As I would watch the Earth sail below and take in everything, all it did was strengthen my faith in God and show me nothing is random,” he reflected. “There’s an order to all of this, and a power far greater than me behind it.”

His memoir, “The Ordinary Spaceman: From Boyhood Dreams to Astronaut,” published in 2015 by the University of Nebraska Press, reflected Anderson’s humility, underscoring his firm belief that he is just an ordinary man with an extraordinary life, a life that, per the American Dream, is possible for other ordinary people.

Anderson has also applied this message to his series of children’s books: “A is for Astronaut: Blasting Through the Alphabet” (2015), “Letters from Space” (2020), and “So You Want to Be an Astronaut” (2023). The first page of the latter answered the question posed in the title with:

“It’s a job that’s super cool.

To ultimately become one,

you must work quite hard in school.

It’s not a job that’s easy.

You’ll need many skills to conquer space.

But if you read through this great book,

In no time, you’ll be an ace!”

The book goes on to describe all aspects of being an astronaut from needing to know how to fix a toilet in space to understanding the importance of teamwork.

“Kids from Nebraska are just like me, and they can be just like me,” Anderson averred. “They can achieve great things. They just have to work hard at it.”

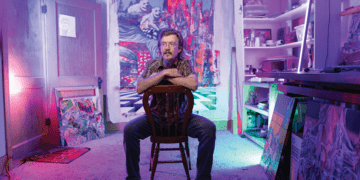

Anderson has applied his own hard work ethic to his tenure at the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum. After three decades with NASA, he retired in January 2013. He was living in Houston with his wife and two children, keeping busy on the speaking circuit and promoting his books, when the museum, located in his childhood hometown, approached him about taking the reins. Already a board member, Anderson well understood the travails of an institution that long struggled financially and administratively. Nevertheless, he accepted, becoming the director in May 2022—the institution’s 10th since 1998.

When he arrived at the helm, he immediately addressed infrastructure issues and focused on stabilizing the organization. He then moved to team building, noting, “At NASA we worked with complex teams. A museum is a complex team as well…I’ve [also] played and coached sports, I’ve refereed basketball, [and] I’ve umpired baseball. I think it’s contributed a lot to my mindset and my leadership and those sorts of things.

“I spent 30 years of having ‘plan, train, and fly’ drilled into me,” Anderson added. “It works for everything. If you’re going to succeed at any mission [or] any project, you plan for it, train for it, or prep for it. And then execute it. As you build mission objectives whose execution requires a team, leadership has to figure out how you do that with that team. That’s what makes it complex.”

That complexity meant restructuring. “We lost a ton of people either through them walking out the door or me having them walk out the door,” he admitted.

Now with a committed team in place, Anderson pivoted to his ultimate mission: “The goal is to make this a destination, and to do that, I’m trying to turn the museum to the future, which is outer space, while standing on the shoulders of the past and the innovations of the Strategic Air Command that won the Cold War. We cannot stay focused only on the ground and in our atmosphere.

“We have to go beyond,” he continued. “The kids we want in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] and staying and working in Nebraska need to focus on space. Space is cool again. Space is where the future lies. Robotics, AI, virtual reality, holograms–that’s the future. Kids want to fly drones, do robotics, launch rockets. That’s what we have to tie into.”

The ultimate goal, Anderson said, is similar to reproducing what captured his attention as a child watching the Moon landing. “We want to entertain, and through entertainment, educate, and with both of those things accomplished, to have guests leave here inspired,” he explained.

Just as he did on spacewalks, Anderson tethers himself to lifelines and relies on experts.

“As a NASA astronaut, I don’t believe in failure. I’m going to bust my butt and do the best I can to make this go. But I also want people to understand I cannot do this by myself,” he said. “I need the support of the Omaha, Lincoln, Council Bluffs metro area, and the generous benefactors, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists in this amazing state.

“I’m relying on CEOs and museum runners in the area,” he continued, citing organizations such as the Durham Museum, Joslyn Art Museum, and Kiewit Luminarium. “I’m trying to learn from all of them. I tell them, ‘I’m no one’s enemy; I’m everyone’s ally.’ My goal is to partner with every single entity I can find.”

That includes the University of Nebraska system (including a collaboration with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s College of Engineering), the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Creighton University, Metropolitan Community College, Southeast Community College, local schools, and major businesses.

“You have to team and partner successfully in order to do the mission, and the mission objective here is to make this place bigger, better, and a gem of the Midwest. My goals are to create an excitement and interest in STEM such that kids will consider staying home in Nebraska to do those jobs. That’s incredibly important,” Anderson said.

He understands that what worked for him may not necessarily apply to current youth. “Kids today are a lot different than kids in my day,” he explained. “We went to museums, and we learned by reading wall panels that explained the exhibit. That’s not the way kids learn and interact these days. We’re trying to make our exhibitions more interactive.”

Take for example, “Leonardo da Vinci: Machines in Motion,” which is on view into early May 2024. In a hands-on experience, visitors can touch and operate reproductions of the mechanisms that the legendary inventor and artist created rather than simply view them behind glass.

As a result of these new approaches, participation in the museum’s educational activities is growing, as are museum attendance numbers.

“We continue to look for ways to provide additional content. We’re always building. We can’t be stagnant. We have to continue offering better and better as we go, and, yeah, that’s difficult. It takes money. It takes staff. It takes time. I tell people we’re not moving at the ‘Speed of Clay,’ but we’re moving forward.”

In a way, Anderson feels his personal speed landed him back in Nebraska with his time at the museum a serendipitous parallel for his time in space.

“The museum opened its doors in 1998, one month before NASA selected me to become Nebraska’s first and only astronaut. The museum opened three and a half miles from where I grew up. That to me is a sign that I’ve come home to try and take this from its first 25 years into its next 25 years, and that next 25 years is focused firmly on the stars and the future. I call it ‘to infinity and beyond.’”

That slice of infinity means this ordinary spaceman is exactly where he’s meant to be.

“I wear that mantel with tremendous pride,” Anderson shared. “I want kids, parents, and the business community to see Nebraska’s astronaut is here. He’s home. He’s giving back.”

For more information about the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum, visit sacmuseum.org.

This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.