When Oakland, California, artist Nyame Brown arrived in Omaha for a four-month residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Nebraska’s biggest city wasn’t what he expected.

No, he wasn’t under the impression we all drove John Deere tractors through the streets. The more-fierce-than-friendly winter weather, though? Well, he knew January in Omaha was bone-chilling cold, but negative wind chills that rivaled the Antarctic wasn’t exactly the welcome he was looking for.

It wasn’t until he found out Malcolm X was born here in the heartland that he learned Omaha held its fair share of good surprises too.

“In light of the fact that Malcolm X was from Omaha and the breadth of Black Panther pride and history here, I saw Omaha in a new light. I saw a place my work could make a bigger impact,” Brown says.

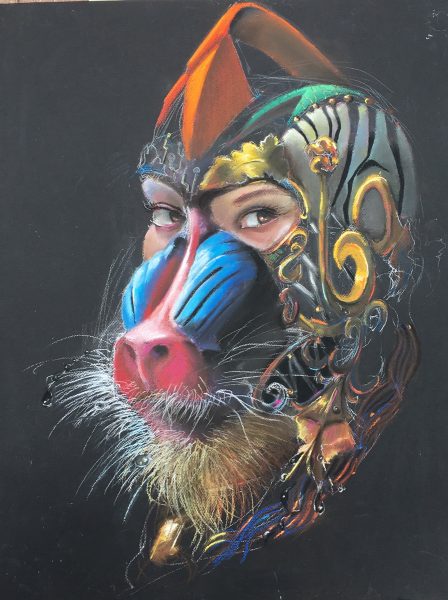

As a multimedia illustrator, printmaker, and painter, Brown has devoted much of his work to exploring the perception of black people, merging aspects of the traditional with the imaginative and illustrating how the larger African diaspora has affected today’s pop culture. He continued this trend while serving as one of Bemis’ artists-in-residence from Jan. 10 to April 6 with his New Black Mythologies series.

r r

r

“It’s got a narrative base with this mega story where random characters come into play,” Brown says. “Fantasy is the key element, but the catalyst was really the idea of slaves having to create an internal world outside of their reality to survive each day.”

To bring to life the inspired and inventive pieces, Brown looked at different folk symbols ranging from tribal tools to signs used by the Crips in Compton, and illustrated them to exist within one canvas. He also strived to be self-referential by including characters from previous work to create new myths where historical-based Afrofuturism meets abstractionism.

Further adding meaning, many of the pieces are symbolically made on blackboards. Instead of chalk, oil paints are used to show that the story of black culture is one that’s permanent and can’t be erased.

“The blackboards also harken back to the classroom,” Brown says. “These stories should already be known, so there’s an urgency to learn.”

Brown’s own story began during the summer of love in late ‘60s San Francisco when his mom, a fashion designer from New York, met his dad, a West Coast painter and sculptor. Watching two creators and growing up in a progressive city, Brown quickly learned art has the power to break down walls and shatter ceilings, especially for those at the fringe of society.

Brown’s own story began during the summer of love in late ‘60s San Francisco when his mom, a fashion designer from New York, met his dad, a West Coast painter and sculptor. Watching two creators and growing up in a progressive city, Brown quickly learned art has the power to break down walls and shatter ceilings, especially for those at the fringe of society.

“Being exposed to art at an early age that showed African-Americans in a non-typical, hyper-realistic way had a profound impact on me,” Brown says. “I then wanted to create images that showed us not as stereotypes and not in the ways popular culture spoke to us.”

This drive led him to receive a bachelor’s degree from the Art Institute of Chicago and later a Master of Fine Arts from Yale University. He now hopes to inspire a new legion of young minds in the same way he was, currently serving as a faculty member at the Oakland School of Arts.

“Every day I see extraordinary talent and hope I show my students, especially those of color, that this career is possible for them,” Brown says.

Even with his devotion to the classroom keeping him busy more than 1,000 miles away, he was drawn to the Bemis artist-in-residence program and knew a break from teaching would be worth the opportunity. From peers and publications, he’d heard about Bemis for years and was itching for the chance to trade coastlines for cornfields.

Not only was he attracted to the prestige of the program, he says the ample creation and living area provided to each artist was a huge draw as well. After all, he comes from a city where space is at a premium, with average rent for a one-bedroom apartment stretching beyond $3,000. Additionally, the program offered access to a multitude of creative resources in the form of tools and actual human beings.

r r

r

“Ultimately, I wanted to broaden my professional network and propagate the work I’m doing,” Brown says.

In today’s political environment, Brown says it’s never been more important for programs like this—one that’s built on attracting artists that make statements on identity, race, and culture—to connect creators and inspire them.

“With the climate we’re in now, black artists have a heightened responsibility,” Brown says. “There’s so much racism going on, so we have to be bold and put forth images that speak to that.”

Rocking a short-sleeved Malcolm X tee while showing off his work during one of those bone-chilling winter nights, it’s clear Brown has gone full blown Omahan. And when his residency is done, he hopes to make the trip from Big O to Big O (that’s Oakland to Omaha, of course) again, creating pieces that bring awareness to the Malcolm X Foundation.

“In all my work now and [in] the future, I hope the community sees themselves reflected back as who they really are,” Brown says. “We’re not mutated characters, we’re not stereotypes, we’re fully realized and that’s powerful.”

Visit bemiscenter.org to find out more about the residency program.

This article appears in the May/June 2018 edition of Encounter.