When Nebraska achieved statehood on March 1, 1867, it was the turning point in a 12-year-long, bitter, and sometimes violent struggle to move the capital from Omaha to…well, anywhere except Omaha.

“Divisiveness festered the moment Congress organized the Nebraska Territory on May 30, 1854. The first territorial governor, Francis Burt, arrived in October to determine the capital’s location. In ill health, Burt was besieged by “every influential man in the territory”—especially those with large landholdings in fledgling towns near the Missouri River. Though Burt appeared to favor Bellevue, a more established settlement predating Omaha, he died just 10 days later and “sought in the grave that repose which it was evident he could never find in Nebraska,” according to James Savage and John Bell in their 1894 book, History of Omaha.

“Our pioneer urban developers knew getting the seat of government would help drive their community’s economy. There was no tax base, and they needed all the federal money they could get,” says Harl Dalstrom, retired history professor, University of Nebraska at Omaha. “Even today we may complain about federal spending, but it becomes legitimate and welcome when the dollars come our way.”

The battle for the capital took shape on both sides of the Platte River, a geographical barrier for people north and south of it, and a political dividing line. The Kansas-Nebraska Act that created the Nebraska Territory also focused on slavery’s expansion. The act would destroy Democratic unity in 1860; it split the U.S. into two political parties, with Republicans primarily in the north and Democrats in the south.

Using the Platte as a line of demarcation, Thomas Cuming, territorial secretary and acting governor, divided the Nebraska Territory into eight counties: four north and four south of the river. Although a census showed more people lived south of the Platte, Cuming announced the first legislative session would convene in Omaha.

A rising young Iowa Democrat, Cuming undoubtedly was influenced by his ties to Council Bluffs and his landholdings in Omaha. “Both cities were interdependent as the West expanded. It’s unlikely Omaha would have existed without its ties to Council Bluffs,” says Dalstrom. The Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Co. supported Cuming’s decision, offering its meeting house on Ninth Street between Farnam and Douglas streets for the session beginning Jan. 16, 1855.

Rancor soon was apparent, with delegates from Bellevue and south of the Platte arriving dressed as Indians, wearing red blankets “to indicate their ‘savage’ intentions toward Cuming,” according to Upstream: An Urban Biography of Metropolis Omaha & Council Bluffs, co-authored by Lawrence Larsen, Barbara Cottrell, and Harl and Kay Calame Dalstrom.

Cuming ignored the blanketed delegates. A.J. Hanscom, unofficial leader of the Omaha delegation, was elected Speaker of the House, supported by his friend, Andrew Jackson Poppleton, a master of debate and parliamentary skill. Buoyed by rich Omahans who bribed delegates with money, land, and promises, the two led a joint resolution on Feb. 22, 1855, naming Omaha the capital, with the ferry company’s meeting house becoming the first capitol building.

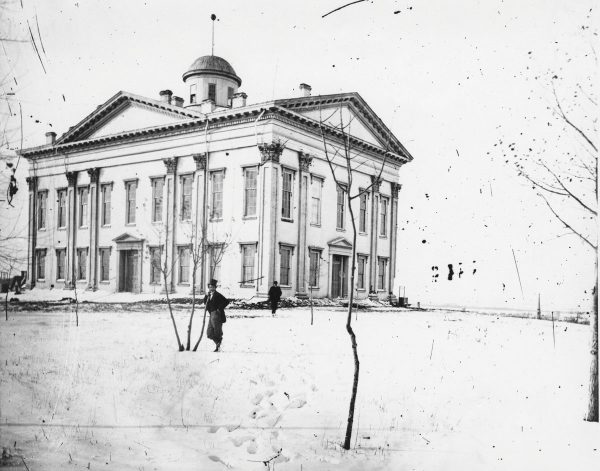

The second territorial capitol was built in 1857 on the site of today’s Central High School at 20th and Dodge streets. Scarcely had the mortar set when Omaha’s adversaries introduced a bill in January 1858 that would move the capital to a new, non-existent town. Omaha did not have enough votes to stop it, so Hanscom and Poppleton began a carefully orchestrated showdown using parliamentary procedure, writes David Bristow in A Dirty, Wicked Town: Tales of 19th Century Omaha.

Through a technicality, Poppleton succeeded in getting Nebraska City’s James Decker, the new House Speaker and an Omaha foe, out of the speaker’s chair, and temporarily replaced him with J. Sterling Morton, an Omaha ally. Intending to filibuster until time ran out on the session’s remaining eight days, the Omaha contingent drew the wrath of Decker, who vowed to regain the chair “or die trying.”

Decker attempted to pry the gavel from the chair’s occupant, then tried to tip him out. Hanscom engaged Decker in a tug-of-war, igniting a brawl with bloody noses and black eyes too numerous to mention, writes Bristow. On the following morning, the anti-Omaha crowd adjourned to Florence (then its own city) and carried a motion to move the legislature there. However, Acting Governor Cuming refused to recognize the Florence legislature, supported by incoming Gov. William Richardson.

The struggle to relocate the capital continued year after year until December 1866, when the U.S. Congress passed a resolution naming Nebraska as the country’s 37th state, effective March 1, 1867. President Andrew Johnson opposed the statehood and vetoed the bill. But Congress overrode it, the only time in U.S. history that a statehood bill became law over a presidential veto, writes Tammy Partsch in It Happened in Nebraska: Remarkable Events that Shaped History.

To placate those south of the Platte River who were considering annexation to Kansas, the legislature voted to place the capital city in Lancaster County. Prior to the vote, Omaha Sen. J.N.H. Patrick attempted to thwart the move by naming the future capital city after recently assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. It was assumed Democrats would not support a capital named after the Republican president, but the Removal Act successfully passed in May 1867.

Gov. David Butler and others toured sites and, by September, had zeroed in on the village of Lancaster, renaming it Lincoln. The state capitol building was completed Dec. 1, 1868, but despite the intervening months, nothing had been done in Omaha to prepare for the move. Many officials, including Butler, didn’t believe Omaha’s citizens would let the capital go.

So, during an evening snowstorm in late December 1868, men surreptitiously entered the Omaha capitol and cleared it of all documents, deeds, and certificates related to the governance of Nebraska, writes Partsch. By midnight the men and pack horses departed, spiriting the documents to Lincoln’s new capitol building, where the Nebraska Legislature would meet within a month. Like the history preceding it, the change was made under a cloud of politics and controversy.

Visit nebraskahistory.org for more information.