Having one’s work shown internationally is a milestone for any artist. Jamie Burmeister has scattered over 5,000 “Vermin” in over 1,000 separate installations across six continents (sorry, Antarctica).r

The tiny, 4-inch ceramic figures, now found in 42 countries and 46 states, are dispersed through a social media experiment he began in 2008. The only requirement for participation is that Burmeister requests that in situ photographs showing the vermin’s new natural habitat be sent to him so that he may document the effort.

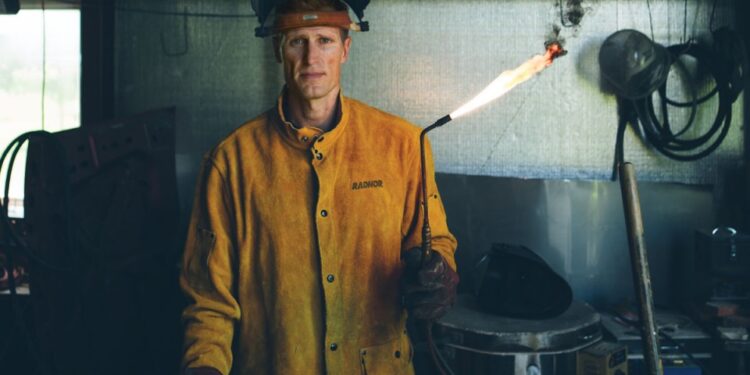

The vermin appellation was inspired by an infestation of starlings in the eaves of the pre-fab building adjacent to his home in Gretna that acts as his studio.

[soliloquy id=”12454″]

“Part of me thought ‘I need to get rid of these birds,’” muses the artist. “Then I had a moment of empathy. I realized that they’re just trying to take care of their families like the rest of us. So I decided to call my little creations vermin.”

The miniature proportions of the otherwise human works evoke mice and other…well, vermin. Whether found in the shadows of the Eiffel Tower or acting as Lilliputian statuary at the Acropolis, the idea is to interrupt the landscape with little surprises, with an emphasis squarely on the word little.

“A woman once found one in Australia before I had even sent any there,” Burmeister says, “I have no idea how it got there.” Another, he explains, went up in flames when an effigy was set ablaze at Burning Man. “A friend in Minneapolis had requested one for the festival and another friend—totally unrelated—happened to find it in the ashes afterward during the cleanup process. He recognized it and took it back to his art venue in Los Angeles. Weird, huh?”

But you don’t need a visa or even a plane ticket to see the artist’s work. There’s plenty of it right here in Omaha, including his Omaha Song sculpture that greets visitors to the Omaha Childrens’ Museum. Part of 2007’s public art “O!” project, the interactive sound sculpture chimes whenever a child sits in the assemblage’s built-in seat. South Omaha Sound Field (2008), situated at the South Omaha Public Library, uses sensors to detect visitors and plays music in homage to the rich tapestry of cultures that have inhabited the city’s historic meatpacking district.

Many other works also employ motion activation and other electronica. A pair of men’s wing tip shoes spring to life in a staccato tap dance when approached. Vermin atop a record player embedded in a retro suitcase—this time aided by a strobe light—boogie to the disco beat of “Do the Hustle” as the vinyl spins. In Funky Junk (2007), the contents of a metal garbage can bump and grind while the container’s lid is struck in a way that mirrors the tinny vibes of a Caribbean steel drum.

His decidedly (and intentionally) crude vermin once took a mere 30 minutes for the artist to craft from clay. Now Burmeister is using a 3D printer for this and other projects.

“Now my vermin can be actual, recognizable people,” he says, “which takes it to a different level because I can cast anyone into my work.”

Burmeister’s gallery and museum pieces have been exhibited in such spaces as the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln and the Des Moines Art Center. And he has been a frequent contributor to shows at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

“A lot of my work speaks to the mundane,” the artist explains, “because that’s the world I live in, the world that most of us live in, I think. There’s nothing mundane about, say, climbing Long’s Peak in Colorado. When I got to the top it was certainly exhilarating, but I couldn’t answer the ‘why’ of it all. It doesn’t make any sense to climb a mountain and it doesn’t make any sense to build sculptures…but I still do.”

Visit jamieburmeister.com for more on the artist.