When Ron Dotzler asked his future in-laws for permission to marry their daughter, her mother said no.

“No? Why?”

“Because you’re white.”

Dotzler grew up in rural Iowa, in a small town of about 300 people. “No diversity whatsoever until I went to college and played basketball. Met my wife, fell in love with her…” He shrugs. “I had no clue.”

After a few years of a successful career as a chemical engineer, starting a family, and building a brand new house out west, things settled down. Then Dotzler and his wife Twany announced they were moving to North Omaha as a sort of pit stop before serving overseas in missions. “Her mother went off on me,” Dotzler recalls. “‘We did all we could to get our daughter out of the ghetto, and you’re taking her back?’”

They’ve lived in North Omaha 25 years now. The Dotzlers never did make it overseas.

Instead, the couple works alongside a small staff and a large roster of volunteers as the Abide Network. The organization is one of many groups in the North Omaha area working to infuse neighborhoods north of Cuming Street and east of I-680 with new work, new homes, and new empowerment.r

Its reputation

rJoAnna LeFlore, interim program director of Bemis Center’s Carver Bank art gallery at 24th and Lake, calls these pockets of activity “bubbles.” “Brigitte over at The Union is a bubble,” she says, referring to Brigitte McQueen, director of the artist residency program at 24th and Burdette. “Love’s Jazz is a bubble. The Empowerment Network. We’re a bubble. If you didn’t grow up in North Omaha, you have no idea what vibrancy is here.”

It’s true that Omahans outside of the vague borders of North Omaha have a certain perception of the area. LeFlore recalls an exchange she had with a bank teller from Bennington after she read LeFlore’s business card. “24th and Lake?” the woman asked. “Isn’t that a bad neighborhood?”

“I just…I took a minute,” LeFlore says with a tired laugh. “And I said, ‘Why would you think that?’ And she said, ‘One of my friends is a police officer, and he told me not to go to that neighborhood.’” LeFlore reverted to her default reaction whenever she runs across someone who relates hearsay. “I listened, and I let her talk.” She pauses. “And then I just told her to come down to Carver Bank and get a sandwich at Big Mama’s.”

The sandwich shop next door to Carver Bank’s gallery and studio space is popular with Creighton students. Grace Krause, a graphic design graduate from Creighton University, has been an intern at Carver Bank for a couple weeks. “I grew up in North Omaha, kind of in the Florence area. I’ve always been a defendant of North Omaha. It’s a really great place; it just has a bad rap.”

LeFlore agrees. “Yes, there are things that happen in this neighborhood that are regrettable, but they also happen all over the city.”

Stats collected by the Abide Network suggest that, while violent crimes do happen all over the city, North Omaha still bears the brunt of them. Dotzler keeps a map covered in red pushpins for every murder (“It’s approximately 820 total”) that’s happened in the city in the 25 years he’s lived in North Omaha. “As you can see, two thirds of them take place right here,” he says, pointing to the area north of Dodge and east of 50th Street.r

Its goals

rHowever, Krause’s comments reflect another side of North Omaha, one that statisticians can’t discount. “When you meet people from North Omaha, they’re exceedingly loyal and proud of where they’re from,” says Othello Meadows, lawyer by profession, community developer by chance, and North Omahan by birth. “You always have this feeling of, like I owe something to where I grew up.” His work in Seventy-Five North Revitalization Corporation offers what he calls the best of both worlds. “It’s challenging work intellectually, but there’s also this greater good we’re trying to achieve.”

Through Seventy-Five North, Meadows wants to bring three elements of greater good to North Omaha: high-quality, mixed-income housing; a cradle-to-college educational pipeline; and a network of community services.

“Neighborhoods with good economic diversity are more resilient and economically stable,” Meadows says. “And we’ll create that with a combination of for-sale and for-rent homes.” That means multi-family apartments, single-family homes, and duplexes.r

“When you meet people from North Omaha, they’re exceedingly loyal and proud of where they’re from.”r—Othello Meadows

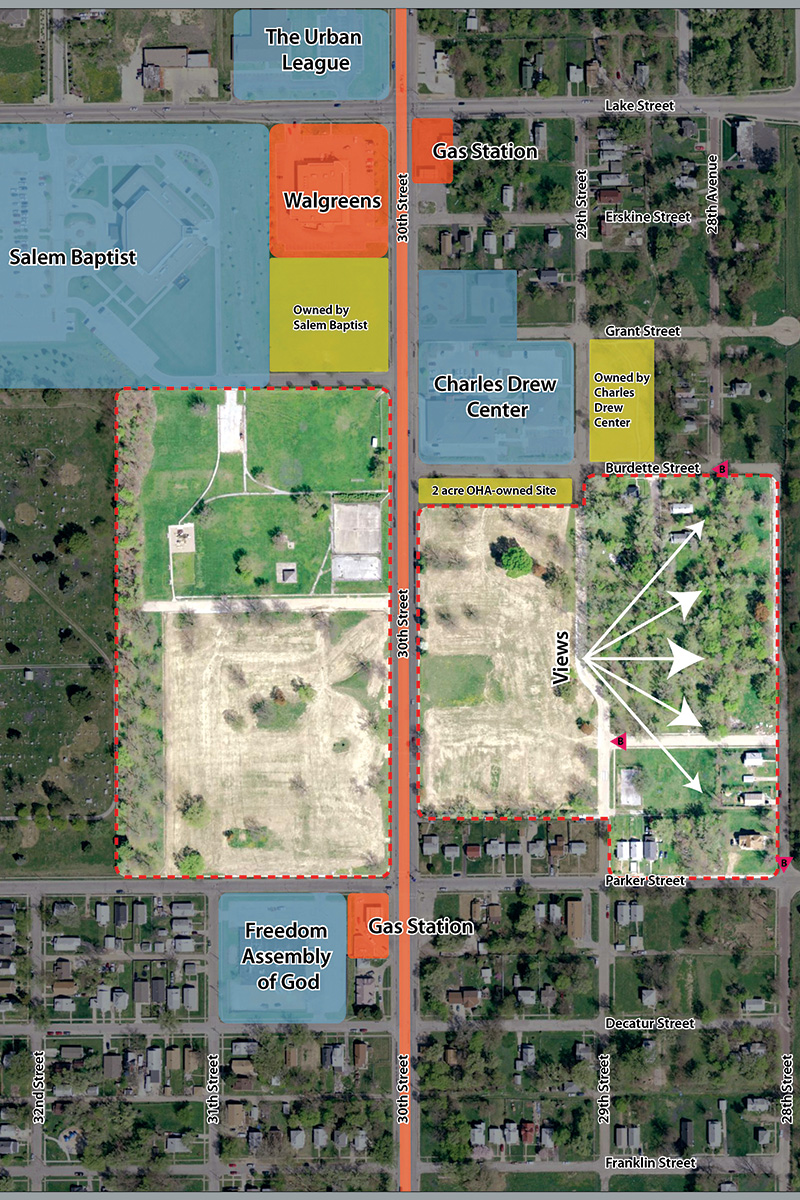

rThe mixed-income housing is probably the closest of Seventy-Five North’s goals to becoming a reality. The organization owns 23 empty acres where a project called Pleasantview stood near 30th and Parker Streets when Meadows was a child. “If you grew up here, you knew about it,” he says. “It was a really tough place.” When he moved back from practicing law in Georgia in 2008, “they were tearing it down. The cost to rehab it was way more than it was to tear it down. Twenty-three acres with nothing on it. Kind of a rare find.” He plans to break ground on a new apartment building before 2015.

Dotzler, on the other hand, says moving away from rented housing is what the area needs. “Seventy percent of these homes are rental,” he says, referring to the neighborhood where Abide Network is based, “owned by landlords who receive money through Section 8 housing. There’s a reason it’s a good business,” he says. “It’s just bad for our community. Fifty-eight percent of rentals are owned by somebody outside of the community.” Dotzler says that rental properties move people around constantly, making a community lack stability.

Interestingly, lack of stability is what Meadows wants to solve as well but with a combination of rental and market-price homes. “Right now,” he says, “you can’t build a house for what you’d be able to sell it. It’s different to have houses that someone can qualify for versus someone who can pay market rate.”

“It’s important for people to have an option to stay here,” LeFlore agrees, though she also would prefer to see more home ownership in the next five years. “Jobs, living situations. Anything that celebrates what’s good will keep people living here.” She adds that another item on her five-year wish list for North Omaha is a strong community development organization. “Something like Othello’s doing,” she says, referring to Seventy-Five North. “Other cities do it. They engage the neighborhoods that exist, and they engage the city to redevelop the neighborhood. So I think in five years that needs to happen. There is no excuse. I think it’s urgent.”

For Dotzler, one point of urgency is neighborhood safety. “The police would tell you a cleaner neighborhood is a safer neighborhood,” Dotzler says, “so let’s mow lawns, let’s pick up trash, let’s fix broken windows, let’s paint over graffiti.” To that end, the Abide Network has for the last six years been steadily “adopting” small blocks of neighborhoods, about 20-25 houses with perhaps four people per house.

As Meadows says, “North Omaha is a huge geographic area. It’s critical to take a manageable bite. The person who says they’re going to change North Omaha is nuts. You have to say we’re going to go to work in this neighborhood. And then hopefully you can establish a model that’s replicable.”

That’s just what Abide Network is doing. Since that first block six years ago, the organization has adopted about 100 such neighborhoods, visiting at least once a month to address the fixes that Dotzler lists. They’d like to reach over 700.r

Its determination

r“We see a lot of emphasis on affordable housing, a lot of emphasis on education, a lot on community services,” Meadows says of the various programs working in North Omaha, “but independently, these don’t get a neighborhood to turn a corner and stay around that corner. You can’t implement these things in any kind of isolated fashion. They really have to work together.”

In fact, one of the reasons the old Pleasantview plot was so attractive to Seventy-Five North (in addition to the vacant 23 acres) was the existence of several already-strong community partners. Meadows lists off just a few: Charles Drew, a federally qualified low-income health-care provider; Salem Baptist Church, the largest African-American congregation in the state; and Urban League of Nebraska, which provides services from job training to parent education.

“It’s our role to coordinate the support that our residents can look forward to,” Meadows says. Housing, education, and services—those elements working together, he says, are what will turn the boat around in North Omaha.

“A small organization like Carver or The Union can only do so much,” LeFlore agrees. “To really market an area of the city, it has to be a communal effort. It has to be a commitment from—well, I don’t know who to put at the table. It’s everyone’s job. Find your place and sit there. Get to the table and have a seat.” She laughs but there’s an element of no-nonsense. “Don’t point the finger and don’t be the naysayer.” LeFlore says she’s tired of hearing ‘We tried that 20 years ago, and it didn’t work.’

“Maybe someone who you meet now can you help you do it right,” she says. “You have to be humble to start a movement. Your ego has to be gone.”