The buried remains of Ice Age mammoths hold secrets to the story of climate change and the rise of mankind.

Mammoths vanished from Earth some 11,000 years ago at the end of the geological epoch known as the Pleistocene, but their story grows increasingly significant today with contemporary discussions of global warming and the alarming rate of wildlife species extinctions worldwide.

As the United States and China crack down on legal channels for buying and selling African elephant ivory— due to a quirk of international treaty regulations—Chinese ivory traders have begun turning to tusks from prehistoric woolly mammoths.

Traditional Chinese ivory craftsmanship has a history dating back thousands of years. Ironically, the continuation of the ancient Chinese art form could become dependent on supplies of ivory from extinct woolly mammoths.

Mammoths are the ancient relatives of modern elephants. Although their closest living relative is the Asian elephant, they also share the biological family “Elephantidae” with African elephants. Paleontologists have excavated their long-nosed (i.e., proboscidean) kin on nearly every continent, except for Antarctica and Australia.

Nebraska has an especially rich history of elephants. In fact, the mammoth is Nebraska’s official state fossil. Mammoths or mastodons have been uncovered in all but three of Nebraska’s 93 counties (every one except Grant, Arthur, and Wayne counties).

“Our elephants first come over about 14 million years ago into North America, and Nebraska is probably the only place in the country where you can find a complete sequence until their demise in the late Ice Age, 10-12,000 years ago. Nebraska is probably one of the few places where you can document the entire history of the Proboscidea in North America,” says George Corner, collection manager at Morrill Hall, the University of Nebraska State Museum in Lincoln.

Nebraska’s State Fossil

r

Mammoths were mythical creatures to the young Corner. As a kid growing up in rural Blue Hill, his family would travel to the capital every year for the state basketball tournament. Across from the Nebraska Coliseum (the tournament’s home prior to the Devaney Center’s construction) was Morrill Hall.

He would resort to temper tantrums if his father wouldn’t let him “go look at the elephants” during their Lincoln visits, Corner says with a laugh.

The paleontologist (who turned 69 in January) stands in the middle of “Elephant Hall,” where gigantic specimens of the state’s rich proboscidean history loom overhead. He has spent 47 years working for the museum—starting with field studies as an undergraduate student of geology, and with the museum’s highway salvage project during and after his master’s in geology.

Corner, who jokes about being as old as the creatures on display, credits the bulk of the collection to Erwin H. Barbour. In 1891, the Ohio-raised Barbour came to the University of Nebraska to head its geology department. Within a year of landing in Lincoln, Barbour had taken charge of curating the museum; he served as its director for roughly 50 years.

The crown jewel of the museum’s Elephant Hall goes by the nickname Archie. That’s short for Archidiskodon imperator maibeni. Archie is a Columbian mammoth (a southern branch of the mammoth genus, which may have lacked the shaggy-coat of its northern woolly mammoth relatives). Both Columbian and woolly mammoths once roamed the grasslands of Nebraska.

“We like to claim that Archie is the largest mounted mammoth in the world, but I’ll show you one thing that Barbour did,” Corner says. “Look at his toes. He’s mounted on his tippy-toes. Now, you can’t tell me that an elephant of that size could stand on his tippy-toes.” (Archie would have likely weighed in the realm of 8,400 kilograms, the size of a large bull African elephant plus 20 percent.) “But Barbour wanted as much height as possible.”

Archie stands in a semi-circle of proboscidean specimens that stretch from prehistoric non-elephants into modern-day varieties—from long-jawed mastodons, to stegomastodons, to mastodons, to the elephant family: mammoths (though a woolly mammoth is not on display at the museum) and culminating in modern Asian and African elephants.

“Some of these critters came over to North America as they were, so there wasn’t a lot of evolution in place. Most of the evolution probably took place in the Old World and then migrated over in the late Miocene,” Corner says, explaining how elephants traveled to Nebraska via the Bering land bridge that once linked northeastern Russia to Alaska.

Asian and African elephants have only recently ventured into Nebraska with help from modern man.

The museum’s Asian elephant specimens came from two that died when a Campbell Brothers Circus train caught fire at Pawnee City in 1904 (only to be excavated by Barbour’s graduate student two years later). The museum’s African elephants on display include the skeleton of an African elephant that had died in a German zoo—acquired before the construction of Morrill Hall in 1927—and taxidermy mounts shot during a 1920s safari by Adam Breede, the publisher of the Hastings Tribune (who contributed most of the museum’s collection of African taxidermy).

“In Nebraska, mammoths became extinct along with 85 percent of all animals larger than the size of a jackrabbit 10-12,000 years ago. And I can’t tell you why,” Corner says, who speculates that climate change, disease, maybe an asteroid, or any combination of such factors, could have driven Nebraska’s mammoths to extinction at approximately the same time that mammoths went extinct worldwide.

Early humans lived alongside mammoths in the landscape that would eventually become the state of Nebraska. But Corner doubts that mankind could have been entirely responsible for the demise of mammoths: “Early Nebraskans witnessed the extinction of these animals, and they were opportunists; they hunted them—but I do not think they were the final cause.”

On remote islands, isolated pockets of woolly mammoths lingered past the species’ mass die-off. The last known living woolly mammoths went extinct on Wrangel Island (a secluded Russian territory in the Arctic Ocean) as recently as 3,700 years ago.

Why did mammoths go extinct? “That’s the big question in paleontology,” Corner says. “Go to the African savannah—we had analogs in the New World to all these animals. In Nebraska, we had elephants, rhinoceros, and camels. Why did all those big game animals become extinct here when they managed to survive in Africa—where there were more humans hunting them? Why? We don’t know.”

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIArRemains of more than 10,000 extinct elephants have been found in Nebraska, but far less than 1 percent of the state has been carefully explored for fossils.

r

r

Elephant and Mammoth Ivory

r

Modern elephants in Africa face persistent pressure from poachers and conflict with human settlements that encroach on an evermore limited range of habitat.

To address the poaching crisis, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (which went into effect in 1975) banned the ivory trade in 1989. But African elephant populations had already collapsed during the decade leading up to the ban, falling from roughly 1.3 million to 600,000 elephants.

Despite decades of coordinated international efforts to protect African elephants, grim statistics remain a reality today: “An elephant is killed every 15 minutes,” according to The Ivory Game, Netflix’s original documentary released in November 2016. The vast majority of that blood ivory is destined for China.

Despite decades of coordinated international efforts to protect African elephants, grim statistics remain a reality today: “An elephant is killed every 15 minutes,” according to The Ivory Game, Netflix’s original documentary released in November 2016. The vast majority of that blood ivory is destined for China.

The CITES ban has allowed several technical loopholes for African elephant ivory. For example: pre-Convention and pre-ban (antique) ivory could be bought or sold, as could ivory harvested from African safari hunts.

After Beijing declared traditional Chinese ivory carving to be an “intangible cultural heritage” in 2006, China participated in a one-off purchase of 108 tons of ivory sourced from naturally deceased elephants in 2008. The sale raised $15 million for African conservation, and the Chinese government has been slowly allocating the stockpile to licensed factories for sale only in the domestic Chinese market. Many environmentalists view the sale as a failure for stimulating demand and providing a front for the laundering of “blood ivory.”

Mammoth ivory is an entirely different beast. CITES does not regulate the trade in fossils or extinct animals. Prehistoric ivory is a way around the global regulation of elephant ivory.

Most of the world’s untouched mammoth ivory remains locked in the frozen permafrost of Siberia. When snows melt during the brief Arctic summer (from mid-July to mid-September), riverbanks often reveal prehistoric remains. Warmer summers means the permafrost is thawed longer every year. That means more and more mammoth tusks are protruding from the ground every year.

Indigenous locals, seasonal tusk hunters, and Russian gangs aggregate the raw tusks in Siberia. Officially, the tusks must be approved for export by the government authorities, but traders (and smugglers) are increasingly taking their purchases directly into mainland China over the land border with Russia, Mongolia, or neighboring countries.

Chinese demand for mammoth ivory has pros and cons. The trade is potentially beneficial for identification of excavation sites—hunting of tusks is incentivized, so tusks are saved that would otherwise be destroyed from exposure to the elements after millennia underground; however, the trade destroys the integrity of excavation sites disrupted by tusk hunters.

According to John E. Scanlon, the Secretary-General of CITES, more than 90 percent of Russian mammoth ivory exports went to China (including Hong Kong) in the past 10 years, with total Chinese imports surpassing 80 tons annually from 2010 to 2015 according to the official trade database of the United Nations.

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIArNebraska’s state fossil is not just ancient history. The mammoth is an important player in the global ivory trade today.

r

r

Changing Regulatory Landscapes

r

Today, on the crowded streets of Hong Kong’s tourist districts, there are roughly half a dozen storefronts that advertise mammoth ivory products for sale. Signs visible outside the mammoth shops promote the legality of prehistoric ivory—tusks of extinct woolly mammoths harvested from the frozen permafrost of Russian Siberia.

Hong Kong played a crucial role in developing China’s niche mammoth ivory market. Before and after the CITES ban, the former-British colony (which became a special administrative region of China in 1997) also served as a key transit hub for elephant ivory—legal and illegal—entering the mainland Chinese market.

Implementation of the 1989 elephant ivory ban brought about major declines in Hong Kong’s ivory carving industry. During the same time period, however, the mainland Chinese economy enjoyed rapid economic growth—boosting demand for luxurious ivory products among the nation’s nouveau riche.

As demand for ivory intensified in China, the government implemented an extensive licensing system, mandatory certification cards for legal elephant ivory products, stiff penalties, and a crackdown on smuggling. Despite the risks, black market ivory dealers continued to cash in on Chinese market conditions to maintain the country’s status as the world’s primary destination for black market elephant ivory (followed next by the United States).

Destructions of seized ivory stockpiles followed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service crushed more than 6 tons of confiscated ivory in Denver, Colorado, in November 2013. Then, two months later, Chinese authorities crushed more than 6 tons of its own seized ivory in Guangzhou province. Over the course of 2014-2016, Hong Kong’s government followed suit with the incineration of 28.86 tons, nearly all of its seizure stockpile—the world’s largest ivory burn until Kenya torched 105 tons ($172 million worth) of ivory in 2016.

Destructions of seized ivory stockpiles followed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service crushed more than 6 tons of confiscated ivory in Denver, Colorado, in November 2013. Then, two months later, Chinese authorities crushed more than 6 tons of its own seized ivory in Guangzhou province. Over the course of 2014-2016, Hong Kong’s government followed suit with the incineration of 28.86 tons, nearly all of its seizure stockpile—the world’s largest ivory burn until Kenya torched 105 tons ($172 million worth) of ivory in 2016.

During a September 2015 meeting in Washington, D.C., President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to enact “nearly complete bans on ivory import and export, including significant and timely restrictions on the import of ivory as hunting trophies, and to take significant and timely steps to halt the domestic commercial trade of ivory.”

In the U.S., tightened elephant ivory laws went into effect in July of 2016 to close loopholes for pre-ban ivory, antiques, and hunting trophies.

Cheryl Lo, a senior wildlife crime officer with the World Wildlife Fund in Hong Kong told Omaha Magazine in late November that she expected Beijing to reveal China’s implementation plan sometime in December. No status update had been released as of the magazine’s press deadline. Hong Kong officials had already announced the implementation plan for the territory’s more stringent ivory regulation in June 2016.

Lo says her research for the WWF found that Hong Kong’s registered elephant ivory stockpile has remained level for many years, indicating that traders were likely replenishing with black market stocks.

She says more research on mammoth ivory in Hong Kong is needed. At this moment, she says there is no evidence to prove systematic laundering or smuggling of African elephant ivory into China under the guise of mammoth tusks. “The current concern is probably at the individual store level—shops that intentionally or accidentally misrepresent or mislabel to consumers that elephant ivory is mammoth,” Lo says, noting that the potential for wrongdoing should still be monitored.

In the future, China’s implementation of stricter ivory regulations will likely increase market pressure on the prehistoric ivory stocks. Being able to tell the difference, then, becomes paramount. Sometimes the difference can be difficult to identify—especially in tusks that are heavily processed or scrimshawed with ink.

Mammoth tusks sometimes exhibit a rocky/mineralized exterior, discoloration from being underground, with denser consistency than elephant tusks. But this generalization does not always apply to high quality tusks gathered from the permafrost.

Likewise, tusks from adult male mammoths are generally larger with greater spiral curvature than African elephant tusks. “But this is not true of all mammoth tusks. Some very much resemble tusks of elephants,” says University of Michigan professor Daniel Fisher, one of the world’s foremost experts on mammoths and mammoth tusks. “There are, of course, juvenile mammoths whose tusks are not large at all, and female mammoths whose tusks do not show much spiral curvature.”

While forensic methods can certify a tusk as belonging to a mammoth, the procedures could damage the specimen or require specialized lab equipment. The most certain means of verification requires a polished cross-section of the tusk. Close inspection of such a surface reveals intersecting spiral curves called “Schreger lines.” Elephant tusks exhibit Schreger lines that intersect with an angle greater than 115 degrees, while mammoth tusks exhibit an angle of less than 90 degrees.

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIA Paleontologists estimate that at least 3,000 elephant fossils remain buried in the average square mile of Nebraska countryside.

r

r

Chinese Mammoth Ivory Dealers

r

Daniel Chan—the owner of Lise Carving & Jewellery in Hong Kong—claims to have first introduced mammoth ivory to the market.

“I began buying mammoth tusks from suppliers in Alaska and Canada in 1983. That was a very busy time for [elephant] ivory. In 1983, nobody wanted to use the prehistoric material, only me. I bought and kept it,” Chan says. “In the early ’90s, nobody was using this material. I was the first Hong Kong person to visit Moscow looking for mammoth tusks.”

In his Hong Kong factory/warehouse, several craftsmen are working at a long carving table. Whirring electrical tools spit ivory dust in the air as they carve Buddhist figures and trinkets from ancient material. There is even a baby mammoth skeleton in the corner of the room. It faces a mountain of mammoth tusks stored in shelves and piled on the floor.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Chan pioneered the supply chain from Siberia to Hong Kong via Moscow. Competition followed. Other ivory dealers moved into his market niche and demand for mammoth ivory steadily grew. Mainland Chinese smugglers buying direct from Siberia and transporting their stocks over the land border with Russia became a major annoyance, undercutting his business.

One of Chan’s peers, carving master Chu Chung-shing says, “I can carve on any materials. I don’t need to break the law to make a living.” Chu owns two upscale shops that exclusively sell mammoth tusk artwork in Hong Kong’s most popular tourist districts.

One of Chan’s peers, carving master Chu Chung-shing says, “I can carve on any materials. I don’t need to break the law to make a living.” Chu owns two upscale shops that exclusively sell mammoth tusk artwork in Hong Kong’s most popular tourist districts.

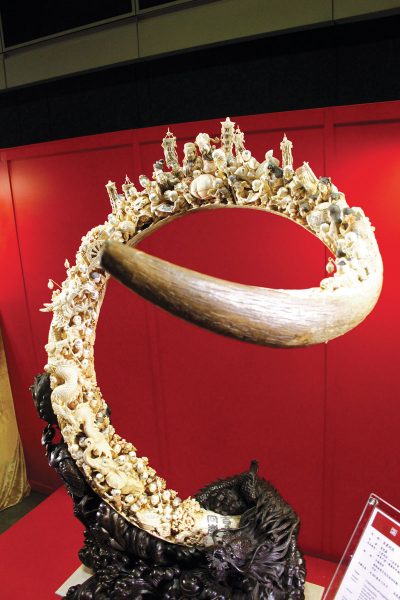

Chu’s Prestige Crafts storefronts glisten with ostentatious carvings, which stretch up and around gigantic, spiraling mammoth tusks. His work was exhibited at the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, and he has had large exhibitions promoted by committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

Chan and Chu shared similar experiences in their search for elephant ivory alternatives.

“The ban was a huge blow to me. I even carved out of ox bone, but only for a short time. Everybody was trying something new after the ban,” Chu says, who eventually found an ideal substitute in mammoth ivory, even though the prehistoric tusks are denser and more prone to cracking than contemporary elephant tusks.

Both ivory insiders emphasize that any new ivory ban from the government should not impact the mammoth ivory trade because of the fundamental difference between the two products.

In Beijing, the China Association of Mammoth Ivory Art Research issues cards to authenticate mammoth ivory products, similar to the system mandated by the Chinese government for elephant ivory carvings. However, use of the mammoth registration cards is voluntary.

Chen Shu, the president of the association, maintains an extensive showroom of mammoth carving arts at his home. Large polished mammoth tusks join examples of historic schools of traditional Chinese ivory carving—from Canton ivory balls carved with impossibly intricate concentric spheres, to Beijing-style painted ivory carvings, and even delicate modern jewelry designs.

Many domestic buyers consider mammoth ivory to be a commodity investment, while others have used the expensive carvings to bribe or otherwise buy influence.

Chen watched prices skyrocket for prehistoric ivory in the past decade. The growth far outpaced changes in elephant ivory prices. He says raw elephant ivory increased from roughly 1,000-2,000 yuan per kilogram in 2003 to 8,000-12,000 yuan per kilogram in 2013; over the same timespan, raw mammoth tusks that once sold for hundreds of yuan rose in price to 30,000-40,000 yuan per raw kilogram.

In the summer of 2016, Chen says that the mammoth ivory market was experiencing a downturn following the central government’s anti-corruption campaign, a slowing Chinese economy, and the Sino-U.S. agreement to strengthen regulation of the world’s two largest markets for black market ivory.

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIA

One mastodon is discovered for every 10 mammoths in the state.

r

rhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5HpfGt5yAjk&t=7sr

rRegulation of Mammoth Ivoryr

r

Mammoth tusks occupy an awkward place between opposing views on the global ivory trade. In the view of Chinese traders, mammoth ivory is an alternative to African elephant ivory that sustains their traditional craftsmanship.

rMany environmental activists, on the other hand, view the mammoth ivory trade as a means of sustaining a hated industry.

Currently, India is the only country to have banned the sale of mammoth ivory. In the United States, four states have bans on the sale and purchase of mammoth ivory: New York, New Jersey, California, and Hawaii.

Nevertheless, Esmond Martin, one of the world’s leading elephant conservationists has cited mammoth ivory as a possible beneficial alternative to elephant ivory (so long as mammoth carvings are produced on a large enough scale that they can be easily differentiated from elephant carvings). Unfortunately for mammoth traders who buy bulk quantities that often include fragments and lower-grade tusks, such scale is not always financially viable.

Mammoth ivory was recently addressed at the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties in South Africa from Sept. 24 through Oct. 5, when national representatives gathered to discuss the state of global wildlife regulations.

In response to the “indirect threat” to elephant populations through the potential for laundering, a draft resolution from Israel urged monitoring of specimens and new mammoth ivory regulations. But the CITES secretariat ruled against the resolution, in part, due to the anecdotal nature of evidence.

Evidence published during the prior year included a 10-month undercover investigation by the Elephant Action League in Hong Kong and Beijing. The undercover report claimed that the Beijing-based Beijing Mammoth Art Co. Ltd had manipulated its connections in Hong Kong to avoid Chinese ivory regulations.

Hong Kong’s environmental groups have mounted a vocal campaign against the territory’s ivory traders. A coalition of local school children protested the Chinese state-owned retail chain Chinese Arts & Crafts (which has outlets across the mainland and Hong Kong), and in 2014, the retailer responded with an announcement that it would sell only mammoth ivory. The commitment did not apply across mainland China, however; the Beijing arm of the company—an enormous shopping mall located near the historic city center—continued to sell both elephant and mammoth ivory products in summer of 2016.

“After the Hong Kong government bans elephant ivory in the new year, Hong Kong’s trade in mammoth ivory will also need a closer look,” says Alex Hofford, an environmental activist and WildAid wildlife campaigner, who alleges that prehistoric ivory trade is a “cynical laundering mechanism for freshly poached elephant ivory.”

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIArThe sale or purchase of mammoth ivory is not regulated in the state of Nebraska.

r

r

A Precious Scientific Commodity

r

University of Michigan professor Daniel Fisher says that China’s mammoth ivory supply chain is cutting into a precious scientific resource.

“Tusks hold the history of a mammoth’s life,” Fisher says. “Tusks are highly specialized incisor teeth, and they grow by adding thin layers of material, only 10-20 microns thick, for every day of the animal’s life. The composition and density of new tusk material varies with the seasons, in an annual cycle, so that a tusk also ends up showing annual layers that are, in principle, something like the rings of a tree.”

Cross-sections of tusks analyzed under a microscope can reveal the mammoth’s reproductive cycles, daily behavior, and might even offer clues into the secrets of global warming through changes in the creature’s diet. “We’re also looking at how they responded to human expansion into the Arctic, so this is also a story of our history,” he says.

For the past 18 years, Fisher has made annual trips to study mammoth excavation sites in Siberia. While exploring the most desolate corners of the Russian tundra, he has traveled by helicopter, boat, reindeer sled, and even hovercraft. But most of his fieldwork is done on foot.

“In many cases, I was following in the footsteps of the ivory hunters, and they are getting all they can. Even if some ivory doesn’t fetch a prime price, it might be worth something, and they don’t leave much behind,” he says.

Sometimes the modern mammoth hunters discover tusks from places where ancient human hunters stored carcass parts. Removing specimens from these sites destroys the archeological context, which scientists could otherwise study. Sometimes, he says the Russian Academy of Sciences will flag tusks for scientific retention. But that’s still rare, and by the time they do, site-specific data is already lost.

Fisher’s research has taken him all over the world. Even Nebraska. In 2006, he examined the Crawford mammoths (then-housed at Morrill Hall in Lincoln). The fighting mammoths, locked in eternal battle, are now on display at Fort Robinson’s Trailside Museum in the northwestern corner of the state.

George Corner remembers Fisher’s visit, and he laments that most of the tusks recovered with Nebraska’s mammoths are in no suitable shape for carving.

“You don’t hear a lot about fossil ivory in Nebraska. Special conditions preserve the tusks, like the frozen permafrost of Alaska or Siberia,” Corner says. “If you were to pick up a tusk from the loess soil around Omaha, you would just have a pile of tusk fragments.”

r

NEBRASKA MAMMOTH TRIVIA “We find elephant remains all the time in Nebraska. But it’s rare to find a skeleton or even a partial skeleton anymore. That’s because of a change in road construction practice. Instead of letting road cuts lay open, the Roads Department will immediately grass them over or seed them with hay. So, we don’t have a lot of time anymore to look at road cuts.”

– George Corner

r

r