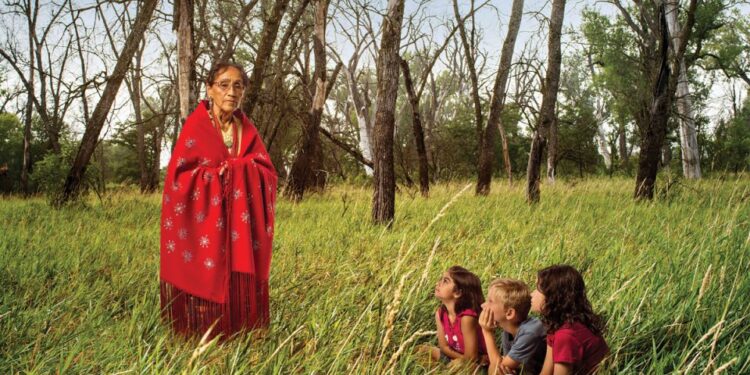

When a language dies, its culture suffers a tragic loss. The indigenous Omaha people—the Umoⁿhoⁿ—are thus in a precarious position. Although there are about 6,000 living members of the tribe, its language is in danger of passing into history. According to Glenna Slater, member of the Omaha Tribe, fewer than 12 tribal members are considered fluent in the language—and many who know the language are unable to teach it.

Slater is one of those rare fluent speakers alive today.

“We’re right here at the edge,” she says. “We lost one teacher in January.”

The Umoⁿhoⁿ settled the Great Plains during the 17th century before losing much of their territory to the U.S. government in the early 1800s, including where the city of Omaha sits today. The Omaha Reservation was established in 1854 and is seated in Macy, Nebraska.

Slater, now in her 70s, grew up on the reservation speaking Omaha as her first language, though she was never taught formally. She did not speak English until she began attending school. Slater eventually attended the University of Nebraska and began a lifelong career in social work, but the compulsion to educate runs through her bloodline. Her mother taught on the reservation as well. “I could never walk in her footsteps,” says the ever-humble Slater.

These days, she gives a weekly course at the UNO Community Engagement Center, teaching the Omaha language to learners young and old. She began teaching around 15 years ago, helping her older sister Winona (now in her 90s) give lessons onrthe reservation.

These days, she gives a weekly course at the UNO Community Engagement Center, teaching the Omaha language to learners young and old. She began teaching around 15 years ago, helping her older sister Winona (now in her 90s) give lessons onrthe reservation.

Many of Slater’s students are older—in their 40s and 50s—but a new batch of younger people have also taken up the mantle. Some of her students are as young as 10 years old. They practice with primers on vocabulary and grammar. They read narratives and traditional stories. “The students want to learn everything. When young ones want to go home and ask their parents, their parents are unable to help, because they were never taught formally or they aren’t fluent.”

Slater tells her students to keep their handouts and everything they acquire, for they may be called upon in the future to pass on the language. Her older students are already teaching their own grandkids, she says.

In tandem with classes at UNO, Slater is also involved in Umoⁿhoⁿ language instruction at Nebraska Indian Community College (NICC) in Macy. Established in 1973, NICC is an accredited land-grant institution providing two-year degrees to residents of the Omaha and Isanti (Santee Sioux) reservations. She has also taught in South Sioux City, and at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha.

Slater speaks of the language with great respect and deference. “There would be something missing if I didn’t know the language,” she says, regarding her relationship with the Omaha Tribe and her ancestors.

“The language is very sacred: if you question the rules and reasoning behind it, you’ll be told it comes from up there,” Slater says, pointing to the sky. “And you won’t get more of an answer than that.” Slater’s respect for the language and Omaha tradition is mirrored in the class, too: “You can only tell the legends during the winter months. If you don’t respect this, strange things will happen.”

Preserving the language has been a difficult process. In addition to the generational challenges, a dictionary was completed only in the last decade, owing much to the contributions of Professor Mark Awakuni Swetland of UNL, who passed in 2015 yet remains a controversial figure among tribal leaders (due to concerns that a non-Omaha person might be profiting from the Omaha language).

Written documentation of the language is limited, and much of the knowledge is still fragmented across the recollections of surviving fluent speakers. Slater herself must defer to the wisdom of her siblings and peers in some cases. “You might know the language,” she says, “but you don’t know it all.”

Her goal with the classes is to continue enthusiasm for the language, and to ensure its survival for generations to come. “I just hope it can go on after me,” Slater remarks, “and I would be happy if I can get even two or three students to become conversational in it.”

Despite the challenges ahead, Slater remains optimistic. Several language revitalization initiatives are underway with the collaborative involvement of elders residing throughout the state. That’s in addition to lessons taught in Head Start, primary and secondary schools, community colleges, and in homes across Macy.

Slater hopes her teaching will expose more people to Omaha culture. “This has been the most fulfilling thing for me,” she says. “When students leave, they want to be hugged. Life is so hard, they need this extra something. And I learn from them, too.”

rhttps://youtu.be/f1nkaPnqONor

________________________________________________________________________________

r A Language Family: William Lynn

A Language Family: William Lynn

r

The mission statement of the Dhegiha Preservation Society states: “the Osage, Omaha, Quapaw, Kaw, Ponca, and Northern Ponca peoples are bound to one another through a shared history, ancient social, political, and cultural relationships, and a common language, the latter of which is in jeopardy of extinction.”

Once a year, Dhegiha speakers and educators gather for a language conference. The sixth annual Dhegiha Language Conference took place in Omaha at UNO’s Community Engagement Center on July 21 and 22.

“Our main goal is to create fluent Dhegiha speakers,” says William Lynn, chairman of the Dhegiha Preservation Society and an enrolled member of the Osage Nation.

The Omaha language is an offshoot of the Dhegiha-speaking branch of the Proto-Siouan language family. In comparison to European languages, it’s a bit like Danish, an offshoot of Scandinavian (North Germanic), which is a branch of the Proto-Germanic language family. The Ponca-Omaha languages are mutually intelligible, and linguists generally group them together.

“It was great that the Ponca and Omaha hosted this year,” says Lynn (Osage). “We’ve had it in Oklahoma for five years. Last year, the Omaha sent a couple of vans down to Oklahoma with 12rfluent speakers.”

r On the Homeland: Vida Stabler

On the Homeland: Vida Stabler

r

Umoⁿhoⁿ language documentation dates to James Owen Dorsey, Alice Fletcher, and Francis La Flesche (the first Omaha-Ponca anthropologist). “But many others have documented our language since then,” says Vida Stabler, Title VII Indian Education Director of Umoⁿhoⁿ Nation Public Schools.

The Omaha Reservation schools currently employ two full-time and two part-time Umoⁿhoⁿ language instructors to teach across roughly 20 K-12 classrooms each week. “We do not have enough teachers to meet demand on the reservation,” says Stabler, who has taught at the schools for 18 years. She recently helped to organize a new teaching group, ToUL (Teachers of Umoⁿhoⁿ Language), and says developing immersion programs will be crucial to language revitalization.

Three years ago, the Omaha Public Schools and the Umoⁿhoⁿ Language Cultural Center produced a language app called “Omaha Basic.” Over the past decade, Umoⁿhoⁿ Nation Public Schools and UNL partnered to complete the first Omaha language textbook (to be released in 2018). The projects relied on crucial contributions by the late Marcella Woodhull Cayou, Donna Morris Parker, and Susan Fremont. In 2017, Umoⁿhoⁿ Nation Public Schools is partnering with the Language Conservancy to produce an Umoⁿhoⁿ textbook for instructors and students.

r An Outsider’s View: Aubrey Streit Krug

An Outsider’s View: Aubrey Streit Krug

r

Aubrey Streit Krug began studying the Omaha language as part of her ongoing Ph.D. in English at UNL. Her adviser suggested that she learn a Native American language, so she started taking classes with the late Mark Awakuni-Swetland, Ph.D., an anthropology professor of Euro-American descent (who had been adopted by Omaha elders).

Streit Krug says she was a minority in the class as a non-Native person. After Awakuni-Swetland’s passing in 2015, she remained among the 10-15 people working on a collaborative textbook. The textbook’s copyright is owned by the Umoⁿhoⁿ Language Cultural Center and Umoⁿhoⁿ Nations Public Schools. The upcoming textbook and the Omaha-Ponca Digital Dictionary are the legacy of her mentor’s lifework.

“Studying Umoⁿhoⁿ is important because this is the land where we are situated. My ancestors were German immigrants in the late-19th century, and I grew up in rural Kansas,” she says, noting that the Omaha language helped her to understand the root meaning of the Waconda Lake near her hometown (a Siouan word for “holy” or “sacred”). “What I knew of the Great Plains was the history of Euro-American settlement. But there is this beautiful, ongoing tradition of Native communities.”

Read also Marisa Miakonda Cumming’s essay, “Speaking to the Future, Honoring the Past” from the same issue, and Charles Trimble’s essay, “A Linguistic Sea Change Across Indian Country.”

This article was printed in the September/October 2016 edition of Omaha Magazine. Story on Glenna Slater by James Vnuk. Sidebars by Doug Meigs. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Visit omahaponca.unl.edu for more information.