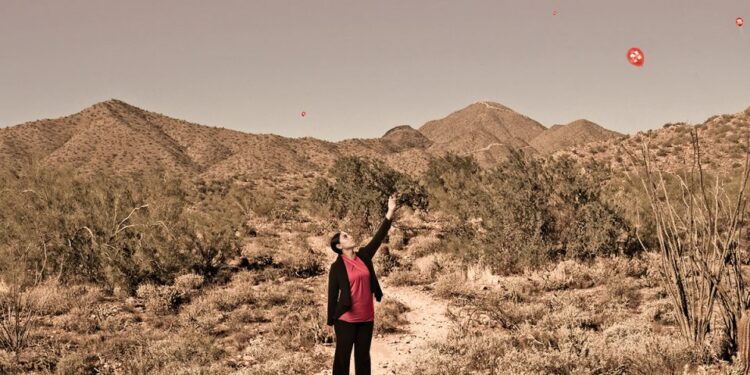

Asterisks (*) designate pseudonyms. Portrait subjects photographed for this article were approached by Omaha Magazine independently from the research conducted by professor Thomas Sanchez. These current, former, and would-be DACA recipients consider Omaha to be their home; they volunteered to share their stories and thoughts about the termination of DACA.

Driving through rural Nebraska, I noticed the battery gauge dropping slowly toward zero. Soon after turning from Highway 30 onto Highway 15, the engine stopped. I pulled to the side of the road. Thinking about my options, I looked in the rearview mirror and saw a sign that read “Batteries for Sale.” I scurried the quarter mile to the farmhouse and knocked on the door. An elderly gentleman answered, and we quickly proceeded to a barn filled with hay. There was an array of car batteries arranged on shelves; I chose the cheapest. We got into his pickup, drove to my car, and installed the battery. Then I drove back to the farmhouse to pay.

When he looked at my check, he said, “Sanchez, you speak pretty good English.” I thought to myself, “Here we go,” but answered calmly, “I better speak pretty good English, it’s the only language I speak” (which was not completely true. I grew up speaking only English and, like many third-generation U.S. citizens, learned Spanish in college). He replied, “No, I know you speak good English, but where are you from?” I answered, “I am from Scottsbluff, way out in the western part of the state.” He said, “No, but where were you born?” I said, “I was born in Scottsbluff.” He persisted, “But where was your father born?” I replied, “My father was born in Texas.” He followed up with, “Where was his father born?” and I answered, “My grandfather was from Mexico.” He did not say anything but he gave me a sigh of satisfaction as if to say, “See, I knew you were from somewhere else.”

I am a light-skinned Mexican-American with a Ph.D. who speaks English with no hint of a Spanish accent. I was born and raised in the middle of the United States. I am also a tenured associate professor at the University of Nebraska-Omaha. I am the quintessential “American,” but personal experiences have demonstrated to me that many in the United States think Latinos are qualitatively different from them—that Latinos are “from somewhere else.” I do not have an immigrant experience, and I do not pretend to understand the immigrant identity. But my light skin color coupled with my upbringing in the Mexican barrio of southeast Scottsbluff has always made me fascinated with issues of ethnic and cultural identity, issues I teach about in all my classes (especially “Race and Ethnicity” for the Sociology department and others in Latino Studies).

My personal and professional interest in identity made me wonder: how do young people, who are “American” in every aspect except legal, negotiate and deal with their identity? How do they make sense of their lives when their personal history and the vast majority of their experiences have taken place in and around Omaha, Nebraska, yet the governmental authorities and the media present them as foreigners?

Throughout my career, most of my research has been conducted with immigrant communities in Nebraska. But my poor Spanish always made it difficult to conduct interviews (much of the consternation was mine, being embarrassed at how bad my Spanish is at times). Interviewing recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (a federal program created by President Barack Obama’s executive memorandum in 2012) offered relief from my occasional language hiccups. Nebraska has about 3,000 recipients, and there are approximately 800,000 nationwide.

The catalyst for my DACA research was an announcement at a faculty meeting of the Office of Latino and Latin American Studies at UNO; private scholarship money was being designated for DACA recipients. I immediately thought that I could continue my research on “immigrants” without worrying about my inability to communicate well because most DACA recipients are in college (71.5 percent of them), and to get into college one must speak, read, and write English. A new research avenue was born.

The following semester, I was readying my application for a faculty development fellowship (formerly referred to as a sabbatical) from the College of Arts and Sciences. A colleague suggested that I get a letter of support from potential interview subjects. It was late on a Friday afternoon, but I called the Heartland Workers Center and was referred to the Young Nebraskans in Action (previously known as the Dreamers Project Coalition). The next week I met with two leaders of the group. Each agreed to write a letter of support to the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

My DACA interviews began with three in December 2015. I conducted seven more interviews in January 2017 after receiving the fellowship. All of my interview subjects were born in Latin America: seven in Mexico, two in Guatemala, and one in El Salvador. At the time of their interviews, the ages of these DACA recipients ranged from 19 to 26. Although not born in Omaha, they were all raised here or in surrounding areas. Nearly all speak English perfectly (without any trace of accent). At the time of the interviews, nine were enrolled in college and receiving above-average marks in their coursework. One had recently graduated. None of them have criminal records.

The following notes and excerpts from my 2015 and 2017 interviews provide a glimpse at the reality of DACA recipients’ existence in Nebraska using their own stories, their own words.

Each of the 10 interviewees articulated a profound love and appreciation for what the United States and Omaha have allowed them to do, the opportunities that the education system has allowed them to pursue. Most of them expressed the view that— if forced to leave their adopted city and country—they are not afraid of returning to their country of birth or to take their talents elsewhere in the world.

Of the 10 DACA recipients interviewed, many of them were politically active and know that being prohibited from voting does not take away their constitutional rights to engage in political activities. A couple of them were timid individuals and specifically stated that agreeing to be interviewed was a political act. One admitted to being shy, saying that their condition of being in the U.S. without authorization made them eschew attention and want to blend in with others around them.

In many ways, the experiences of the Nebraska DACA recipients I interviewed are similar to what academic and other research has revealed to be experiences nationwide.

Lourdes* came to Omaha when she was 6 years old. Now a community organizer in her mid-20s, she had this to say when asked which country she belongs to: “I tell people that my blood is Mexican, but my heart is American, because the two work with each other and they would not be able to exist without one another. So, that’s the best way that I can answer that question, just because, like I said, I was raised in the U.S., with U.S. principles and morals, but my culture is Mexicana and they work together to create who I am.”

All 10 of my DACA sources speak English and Spanish. Each speaks English well, and only one did not speak Spanish well. Most of them speak Spanish with parents and elder family members but English with others, including younger siblings. Only one of the sources claimed their parents could speak English well.

They have internalized the Nebraskan and Midwestern culture, especially in terms of work ethic. Not only driven by the work ethic of those around them, they felt obligated to prove (to themselves, to family and friends, and to society at large) that they will be successful. They work hard at jobs, school, and in their community. While they all claimed cultural connections to their country of birth, their inability to travel outside the United States makes those connections appear to be mostly imagined. They are connected culturally in ways that a second- or third-generation Mexican-American might be connected to their ancestors’ nation of origin. Their “Latino” culture is largely a U.S. Latino culture.

The vast majority of their personal experiences have been positive in Nebraska. Aracely* says: “In one of my classes in high school, I was told that Nebraska was one of the most racist states in the United States, and I thought that was pretty funny because I myself never really…saw myself being discriminated against for being Latino or for having Hispanic descent; however, when I found out that Nebraska was the only state left that didn’t give drivers’ licenses to DACA students…I realized that there’s just, like, so much indirect racism.”

All of the interviewees shared a positive image of Omaha, and almost all of the sources had mixed feelings about the conservative politics of the state. Nelson* (who says he migrated from El Salvador when he was “1 year old, maybe less”) was active in getting legislation passed such as LB 623 (which gave them the opportunity to get a driver’s license).

“I know there are a lot of Republican senators who really care about us, but then I believe everything is just politics,” Nelson says. “Maybe they do care about us. But their constituents, they’re very hard-line anti-immigration, and because of that we’re not getting the support that we really deserve in the government. But, in that sense, I understand. But then again, I don’t think the Democrats are doing enough for us either, and so it’s really difficult, and right now I just have a very negative attitude about what the government is doing for immigrants, especially with the rhetoric that Donald Trump has been spewing all throughout his campaign and continues to do so. It just makes things worse [for everybody] and it doesn’t do anything for immigrants.”

Interviewees reported few, if any, incidents of discrimination or overt prejudice in their everyday experiences in Omaha; however, several of them shared anecdotes of close friends—citizens who happened to be darker-skinned Latinos—having more overt discriminatory experiences than they as DACA recipients did.

Some of the 10 DACA recipients had arrived in the United States a bit later in life and always knew they were not authorized to be here (the age of arrival ranges from 10 years to three months with the average being 5 years old); others had no idea of their undocumented status until later in life.

Interview subjects mentioned “shame” when discussing their parent’s feelings about being in the United States without authorization and “stigma” when discussing their own feelings; the same words were used by Leisy Abrego (a University of California-Los Angeles professor who was herself part of the wave of Salvadorian immigration to L.A. in the early 1980s) in her groundbreaking research on DACA recipients in California.

Some did not find out they were unauthorized—or they did not realize how it would affect them—until their junior or senior year in high school, when they began to fill out college and scholarship applications and were asked for a social security number.

All of them learned of the severity of what it really meant to be unauthorized when they could not get a driver’s license, even after they received DACA. All feel, to one degree or another, they missed out on that and other rituals associated with being a kid or “growing up.”

As young children and teenagers, they were unaware of the consequences: both the social stigma and the legal pitfalls. They had been protected from the vagaries of their undocumented legal status—by teachers, counselors, churches, and other well-meaning adults and institutions.

Many of my interview subjects used terms like “coming out” for disclosing their unauthorized status. The phrasing seems to contradict previous assertions of “no shame.” But it could be that their general feelings simply changed from when they were younger and they did not see the effects as readily. As they grew older, the negative consequences of the same undocumented status became more acute and meaningful in their lives. The driver’s license issue is just one glaring example (one for which Nebraska gained notoriety in nationwide immigrant advocate and anti-immigration circles).

Due to a fear of immigration and law enforcement authorities, none of the people I interviewed had traveled much, if at all, outside the Omaha area. Some of them had been to Lincoln (on recruitment visits to UNL) and a few had traveled once or twice to Iowa or Wisconsin to visit family. Many admit that they love Omaha, they love Nebraska (even though they had not been anywhere in Nebraska outside of Omaha), and that they desire and plan to stay in the Midwest region of the country. Most want to stay in Nebraska and/or the Midwest in order to pay back those communities for the opportunities that they have been able to access.

In terms of social connections, about half of the interview subjects reported having mostly white friends or friends who are a mix of different races and ethnicities; the other half have friends who are mostly Latino. More than one of them mentioned the difficulty of meeting new people, especially in the romantic realm, and not knowing what or when to tell them about their immigration status. One respondent stated that they were afraid to tell a new dating partner about their status for fear that the other person would wonder if they were just dating them so they could marry and get their immigration papers fixed. Another spoke of being in a long-term relationship with a person who still does not know that they do not have government authorization to be in the United States.

When I began these interviews, I was interested in the question of criminalization. How did undocumented youths see their own “criminalization” in light of what labels have been placed upon them by some elements of society?

The research question turned out to be of little concern to my sources, with eight respondents emphatically stating “no” when asked whether or not they felt like criminals. Two others were not sure or had felt like criminals at some point in their life but changed their mind as they had matured. Almost all had mixed family statuses with little brothers and sisters who were citizens and parents who were unauthorized. At least two had fathers who had been deported.

Although born in foreign countries, their hearts and souls are firmly rooted in the United States, a country that officially rejects but tolerates them. Lourdes, the community organizer, says: “I do plan on staying in Nebraska…my skin and bones are still getting used to this weather, but beyond that, absolutely. I love Nebraska, and the fact that we are helping change the political landscape and [making] it be a place that welcomes is very enriching, and I’m beyond glad that I’m able to be a part of that with dedicated individuals. So as hard as it is knowing that we are going to be at the forefront of what’s happening and the change for our future families and friends… It’s of course [worth it]…and I love Nebraska and Omaha in general…I don’t ever take for granted what I do. And I feel like that journey wouldn’t have been possible had I not had the [immigration] status that I did. So it just enables me, helps me appreciate and really understand the significance of what I’m doing for myself and for my community.”

I came away from the interviews with a sense of awe.

As I interviewed each of the 10 young people, I had the sense that each person will not only be successful; they will be high-achieving contributors to the nation’s society and economy. Rather than being afraid for themselves, their worries overwhelmingly focused on the future well-being of their parents, siblings, friends, other family members, and people in situations like theirs who may have not had the tools, skills, or maybe just the proper connections to navigate the educational system.

I often wonder why anti-immigration advocates seem determined to cast out those who would otherwise be helping to pay for Social Security. In the end, it is not about their contributions to the economy, it is about what kind of society we choose for ourselves and the people we welcome into that society.

This article was printed in the November/December edition of Omaha Magazine.

View the condensed version of Omaha Magazine‘s video interviews with DACA current, former, and would-be DACA recipients:

Find the full interviews for the portrait subjects here:r

- r

- David Islas Ramirez: https://youtu.be/dP4YD4nOY1Qr

- Yanira Garcia: https://youtu.be/NVCxKB5NCKAr

- Luisa Trujillo Estrada: https://youtu.be/ut_uVG6LGn4r

- Armando Becerril: https://youtu.be/yyO6ICKiwGYr

- Daniela Rojas: https://youtu.be/BJYOZeRpHwYr

r

r

r

r

r

r