Robert Owen sipped a drink, smoked a cigar, and enjoyed the view from the back end of his “yacht on the tracks.” He didn’t have a care in the world. The rush of catching a plane, loading luggage, or dealing with the airport crowds faded in favor of the looming Rocky Mountains. The train chugged along at a leisurely pace after it left the station in Chicago. The pressures of being CEO of Owen Industries, a metal fabrication business, drifted away with the chugging of his 1928 vintage train car. The slick silver, red, and blue Pullman gleamed at the rear of Amtrak’s westbound No. 5 California Zephyr. He, along with other members of the American Association of Private Railroad Car Owners (AAPRCO), headed to Napa Valley along the sturdy steel of the rail tracks just as their ancestors may have done in the late 1800s. The countryside, unhindered by automobiles or highways, seemed so primitive one could almost imagine an outlaw waiting in the wings for an old-fashioned train robbery.

The inside exuded the same plushness as the outside. The lounge’s soft blue chairs, creamy leather sofa, and refinished woodwork is the picture of refined elegance. The dining room is a throwback to the original Pullman. A long table is covered with a white tablecloth and linen napkins. Dinner was prepared by a chef and guests could partake of caviar, a filet, or champagne. Photos of the Boston Red Sox’s Ted Williams sit on a table, showcasing the history of its famous passenger.

It’s a timeless travel adventure. Owen, 75, has taken 10 trips across the rails to different states in his very own private car. In his youth, taking a train was a popular way to travel. The rooms were fancier and bigger back then, but it allowed time for the family to bond and enjoy the countryside.

“Riding a train was a real treat,” Owen recalls.

Owen and his grandfather would hitch a ride on the Burlington Zephyr, a stainless steel speed demon. The diesel-powered and electrically controlled locomotive blew Owen’s mind. He thought it would be cool to own his own railcar. The thought never really left him, even after air travel boomed in popularity.

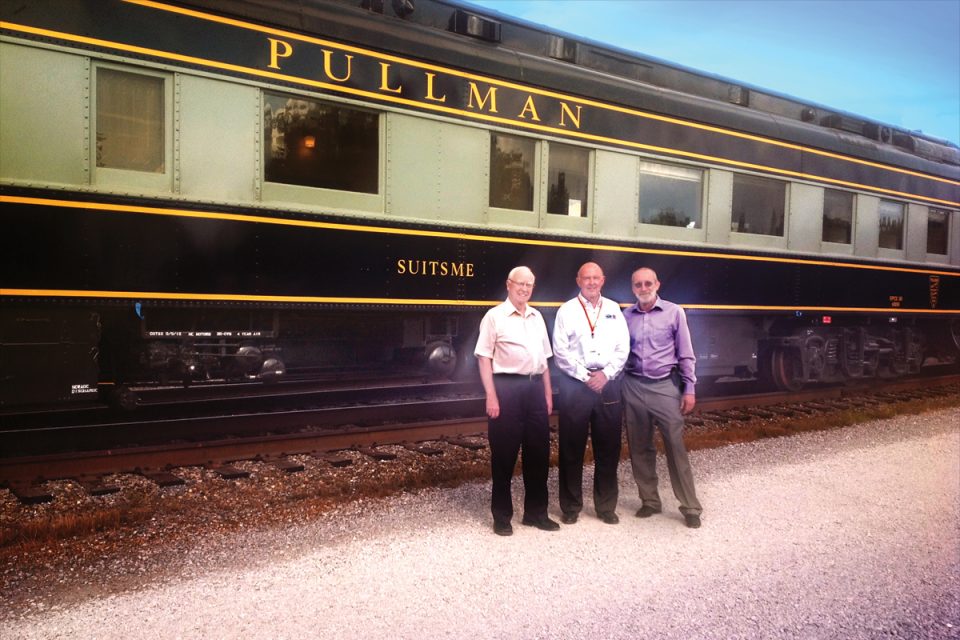

In 2011, Owen turned his boyhood dreams into reality. Owen contacted Warren Lucas, who worked at Union Pacific at the time, to purchase the executive car of a former railroad tycoon president, who affectionately named it Suitsme. A private rail car can cost anywhere from $300,000 to $800,000. That’s why Terry Peterson, president of Omaha Track, jumped on board to become co-owner of the former Bangor and Aroostook railcar.

But the cost of owning a railcar doesn’t stop with the initial price. Many of these antiques require refurbishment and restorations. Peterson laughs, saying he has sunk anywhere between $100,000 to half-a-million into this car. Owen says his particular railcar needed updating “on and under the frame.” Peterson elaborated that this meant new wheels, axles, suspension, brakes, and more. The railcar also needed a new HVAC system, water and holding tanks, a new electrical system, and plumbing fixes. An outside company from New Jersey that repairs passenger cars did most of the work.

To those who can afford it, however, the luxury of traveling in a private railcar is worth any cost.

“It’s like owning a private jet or like being in a five-star hotel,” Peterson says. “The goal is for the food to be special, the service, everything.”

The first trip aboard Suitsme took Owen and friends down to Chattanooga, Tennessee, followed by others to Washington, D.C.; Seattle; and wine country in California. Members of the AAPRCO will sometimes attach their cars to the same engine for trips, which increases the chances for comradery or a party on wheels.

“It’s a fabulous way of seeing America. It spoils you. It is the very essence of enjoying the journey,” says Julie King, executive director of AAPRCO.

AAPRCO hosts excursions that include tours, museums, and sights, sometimes of historical railroad spots. The membership fee of $90 a year includes a subscription to their magazine and an invitation to an annual convention.

Additionally, there are costs for fuel and parking. Amtrak rates for trips have risen to $3.26 a mile to pull the private railcar plus $155 or more for overnight parking. That doesn’t take into account the cost of the crew, which includes a cook, steward, and mechanic.

Yet, the cost doesn’t stop Owen’s love for his hobby. He purchased a second railcar with co-owner Mike Margrave, a 1953 golden beauty called Promontory Point. It is named for the site of the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad, when the Union Pacific and Central Pacific rails were reportedly joined by a golden spike in 1869.

“They [my family] all thought I was crazy, and I probably am,” Owen says with a laugh. “I always wanted to have one, and now I have two.”

The added benefit of two cars is a more spacious voyage, with more bedrooms and bathrooms. Since then, Owen’s son and daughter, along with his seven grandchildren, have made use of them. Some will say railcar travel is a disease, an obsession, that hooks owners from every walk of life once he/she takes the first step back in time. Sure, some things have changed. Cigars are no longer allowed, but Owen still enjoys waving to people as the train disembarks for unknown adventures.

Visit aaprco.com for more information.

This article was printed in the August/September 2018 edition of B2B.