The “Fab” in Metropolitan Community College’s FabLab stands for “fabrication,”rbut the space is actually pretty fabulous in its own right.

“It’s still a relatively new concept,” says information technology instructor Hugh Schuett, who works in the MCC FabLab with fellow instructor Jamie Bridgham. He explains that fabrication laboratories began only a few years ago as an outreach project of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT’s ultimate goal is to build a network of small-scale workshops that, through digital fabrication, can create almost any object and make the means for invention accessible to nearly anyone.

MCC’s FabLab became the 145th such facility in the world when it opened less than a year ago. The number has since grown to over 200, Schuett says. Through access to MIT servers, MCC’s FabLab maintains a constant connection with other sites all over the world.

Fab labs contain a spectrum of equipment that include computer-controlled laser cutters, precision milling machines, sign cutters, 3D scanners and printers, and, of course, the software that makes integrated design, manufacturing, and project management possible. MCC’s FabLab is currently residing in a small space tucked away in the library building on the Fort Omaha Campus, but it’s rapidly outgrowing its quarters. While awaiting a permanent home in the Center for Academic and Emerging Technologies building now under construction and slated to open in 2016 or 2017, the FabLab will soon be moving to The Mastercraft building in NoDo.

“It will be an interim place where we can do dirty, noisy, messy stuff,” Schuett says.r“What we’ll have the ability to do is get all our equipment, get all our processes in place, so that when the new building opens up we are ready and we’re moving in and we’re functional at the same time.”

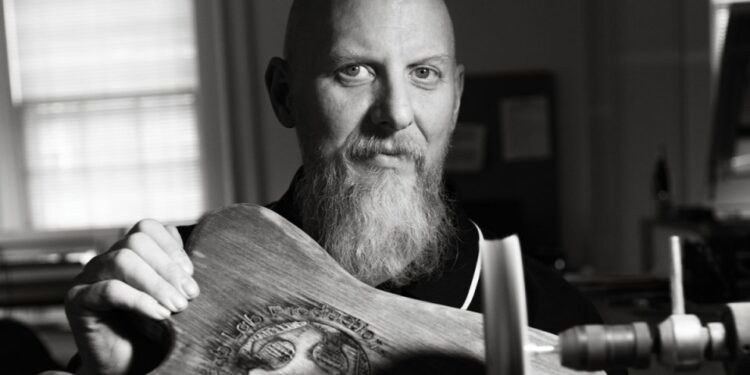

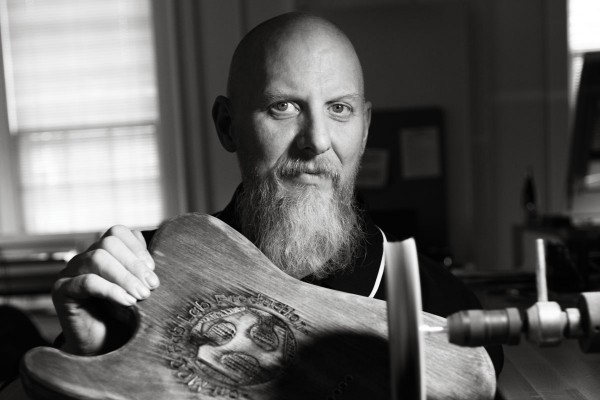

MCC students may eventually do production work for small businesses and entrepreneurs, Schuett says, but as the lab is getting established community members have access through two noncredit courses. An increasing number of instructors are integrating the FabLab into their courses, like the How to Build an Electric Guitar class. MCC is also developing relationships with small businesses, entrepreneurs, and inventors in the community to further explore the program’s capabilities.

Eventually, rapid prototyping accessible to private citizen inventors is expected to transform the currently slow and costly prototype manufacturing and product testing process, ushering in a new world of entrepreneurship, Schuette says. And he adds that the technological potential is infinite. 3D printers can already create items composed of substances from plastics and clay to chocolate and bone-compatible material on a scale from circuit boards and jewelry to machinery and building segments. Someday, anything that can be scanned or three-dimensionally modeled will be able to be fabricated.

“The more equipment we get, the more we’re going to be able to do,” Schuett says. “The more people come in, the more ways we find out how to use the equipment we already have.”