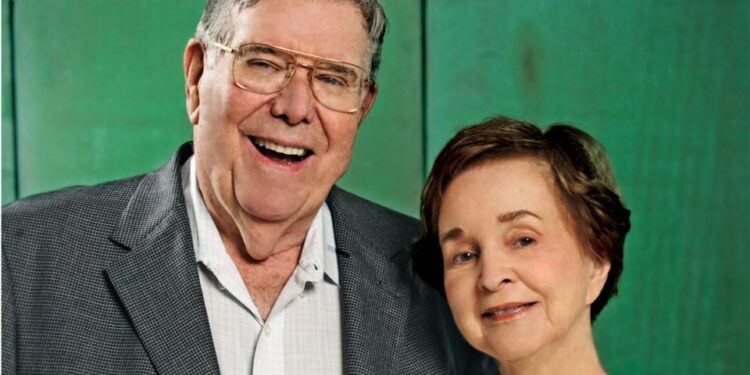

Dick and Mary Holland didn’t sit in their well shaded home all summer, waiting for the grand opening of the performing arts center that bears their names. By early May, they’d toured construction progress a dozen times.

But the privilege of joining them on a progress tour in late August proved that they see the great effort with fresh eyes on each visit. Both Dick and Mary asked pointed questions of project manager Steve Smayda, and Holland had friendly greetings for the men laboring on the job.

He’d recently treated the workers to ice cream, hiring three of those ding-dong trucks and sending them to the 11th and Dodge work entrance. “I’ve never been around guys so damn proudrof what they are doing,” he says. He’d long since donned his yellow hard hat to become the first to sing from the new concert hall stage.

“La Donna Mobile?” “No, something from Faust,” he jokes, but more like scales. The former member of the Opera Omaha chorus then offered a few baritone notes.

Make no mistake, the Hollands are enjoying their singular involvement, starting with a major gift and a hand in planning the $92 million Holland Performing Arts Center at 13th and Douglas. Any discomfort comes from their more specific roles in that Oct. 21 grand opening performance, emceed by Oscar-winning actor Richard Dreyfuss.

A news story reported that Dreyfuss was chosen partly because of starring in the movie, “Mr. Holland’s Opus.” That got a groaning “I hope not” from Omaha’s Mr. Holland. As for that opening night, “We’re certainly going to be there, but I haven’t asked for anything.”

Such reluctance won’t surprise anyone who has followed the story of the Hollands and their “enormously successful” investment with Warren Buffett. When the Omaha World-Herald ran a big spread on their philanthropy (“Giving Their All”) a few years ago, it was noted that they don’t talk about their fortune “and declined to be interviewed” for the article.

When questioned by this writer last year for the University of Nebraska at Omaha magazine Alum, Dick added to the basic account in a Buffett biography. Married a month after his 1948 graduation from then Omaha U., Holland took over his father’s advertising agency and the newlyweds moved into their present home near 80th and Pacific in 1957.

That left him short of funds when he found Buffett, the first person he’d met whose investment ideas “made sense.” So Dick borrowed $10,000 on his life insurance policy and Mary contributed a “significant” amount from her own resources. The rest is history oft-told by biographers of “the Oracle of Omaha”: The insightful ones who invested $10,000 with Buffett in 1957 and let it ride through the founding of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., saw it grow to roughly $280 million.

Still, the Hollands remained in that same modest house, but gave away millions to causes ranging from the fight against poverty to arts organizations. Last year, $43 million remained in their charitable foundation, despite the many gifts.

Anyone tempted to second-guess their large contribution to the Holland Center must challenge two points: “Our top giving goal is to raise a whole lot of people,” especially children, “out of poverty.” And they both place great importance on the arts.

Born in Dundee and a graduate of Brownell Hall, Mary majored in childcare at Mills College in California. Dick, who grew up near 60th and Pacific, and Mary had attended the same Brownell dances, but didn’t meet until after World War II, when he returned to studies at Omaha U. “Mary still loves to dance,” Dick says, “and she’ll dance till the stars fall out of the sky.”

On music, “We’re all over the map,” he observes. “I like the modern Russians, Mozart, Brahms, some Beethoven. Mary likes some things I don’t particularly like, those compositions full of approaching doom. We go to some Broadway shows twice. We always go to Fiddler on the Roof twice, but this last time we were in Arizona.”

Mary puts it this way: “Life isn’t just reading, writing and arithmetic. It’s more than that. Music penetrates the soul. It causes us to reflect. Painting, dance and creative writing work that way, too. Observe the joy it brings. Not just the applause and cheers, but the quiet pleasure.”

Though Dick’s singing in the Opera Omaha chorus was his most recent performance participation in local arts activity, he came close to a career as an artist. His father, Lewis, had been a talented painter, and Dick won an art award while playing football at Central High School.

“Growing up,” he recalled, “I was nuts about Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton. Now I like the contemporary—the Jackson Pollock is the best art at Joslyn.”

He started college planning to be a chemical engineer, like his older brother William, but military duty in that field turned him to art on his return to the classroom at Omaha University, the alma mater of Dick and his three siblings. “I never carried it far enough,” Holland explained. “I was just learning to draw, to paint, but I was still an amateur.”

He dreamed of going to the Art Students League in New York City, but then met Mary. “She wasn’t going with me, and I needed to make money” to support her “in even half the style to which she was accustomed.”

That explains the goal, one he now calls “tasteless,” that ran beneath his senior photo in the university yearbook: “To have money and a business in art and advertising.”

That business, for many years, was known as Holland, Dreves and Reilly, second only to Bozell and Jacobs in its advertising/public relations heyday. (Valmont, UniRoyal and Omaha National Bank were prime accounts.)

Dick didn’t entirely abandon art when he delved into vocal music. He tried some life drawing, some painting. “The thing about it,” he notes, “is I’m just so totally into myself when working on canvas,rso absorbed.”

But football and fencing gave way to golf. The tall man shot in the upper 70s in his prime at the Omaha Country Club, and freely advised fellow golfers. And painting gave way to five years of voice lessons, studying with the Germanic Josie Whaley.

“She’d say, ‘Meester Holland, if you keep doing the baaaa, the scales, you’ll have a remarkable voice.” In Dick’s words, “Keep training and your range is raised a hell of a lot.”

In the course of their board work and their contributions to the opera and the symphony, the Hollands and others developed a vision that led to the Performing Arts Center opening in October. Joan Squires, in her third year as president of Omaha Performing Arts, cites that vision and “Dick’s perseverance for eight years or more” as a key to the center’s completion.

She has toured construction with the Hollands and “wished I had a tape recorder and a camera. It’s a thrill every time thru with them.” She joined them again, along with their daughter, Andy, when this writer shared the experience.

In particular, Squires recalls Dick’s first reaction to the downtown center: “It’s so big.”

Yes, that was a surprise, he admits, having viewed it first in model form. He’d visited other arts centers and the committee headed by World-Herald publisher John Gottschalk added sites as far as Vienna and Lucerne to their tours.

The Hollands helped engage architects famed for the renovation of Carnegie Hall and design of the Clinton presidential library, along with the Fisher Dachs Associates as theater consultants who’d done work for the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and the Radio City Music Hall in New York City. Even more intriguing were the acousticians from Kirkegaard Associates.

“I had to learn how to pronounce AK-u-stishun,” Holland noted. And, of course, to test their talents by singing that passage from “Faust.”

He stood on that 64 by 48 feet stage in the classic shoebox configuration of the main concert hall, 80 feet wide by 180 feet deep, where 2,000 will hear sounds ranging from soloists to full orchestras. Later, the Hollands will sit sans hard hats in what the architects call a surrounding of “warm, fine-grained woodwork.”

Concert-goers won’t see that the hall is “sheathed in zinc,” but before entering they’ll eye the great illuminated glass lantern above and they’ll see that the acoustically isolated hall is clad in limestone. A thousand will sit at orchestra level, with 400 in the mezzanine, and 600 in the upper balcony.

Squires is quick to remind that the $75 to $150 tickets are just for opening night, with early activities including two or three free events, plus tours, and other performances in the $35 and $45 range.

The “black box” recital hall will seat 450, and the terraced courtyard, designated as a third performance venue, will hold 1,000. The Holland Center will house parties and educational activities as well. The Orpheum, fully equipped with stage rigging, will remain home for Broadway musicals and other events.

Squires, who came to Omaha from the Phoenix Symphony, commented on the wide range of upcoming performances. “One of the reasons it’s a joy to work with the Hollands is because they bring such broad understanding and interests,” she says. “They’re eclectic, but don’t impose their taste. It’s a low key, quiet influence, and we respect their desire to stay out of the spotlight.”

“We won’t attend all the early events,” Dick adds, “but there are some we’ll definitely see.” They especially anticipate Renée Fleming’s appearance with the Omaha Symphony on Dec. 9. “I was president of Opera Omaha when she first sang here.” He also takes pride in their presenting of the great Beverly Sills, but notes that the biggest local paycheck of $100,000 went to Placido Domingo.

But now comes that grand opening with Dreyfuss, the other “Mr. Holland,” and a program that includes Oscar winner Alexander Payne, U.S. poet laureate Ted Kooser, bandleader Branford Marsalis and others, including the symphony and the opera chorus. Squires takes pains to point out even this higher-priced event is not black tie, but cocktail attire.

Tickets went on sale in mid-August and began to sell quickly. A pre-event cocktail party sold out almost immediately.

Lest purists fear that Dick Holland’s brief aria was the only pre-testing of the acoustical marvels, it must be noted that an extensive “tuning” process gave professional musicians ample opportunities to experiment with the new concert hall, even before a long rehearsal period.

During the run-up to the grand opening, acousticians “tuned” the hall. Musical ensembles of varying size and style (classical, symphonic, chamber, pop, rock and jazz) performed during the weeks of late September. At each performance, acousticians positioned each of the moveable acoustic reflectors and panels, matching the reverberations to the size and sound of each group. The positions were locked into preset configurations, which could be used for future performances with ensembles of that size and style.

That’s fine by Holland who recalls his first piano lesson: “Auto stop, I’m the cop, drivers take warning.” The memory brings a smile and makes him happy to give the stage to the pros while he sits back with Mary in Row P of the Holland Center and enjoys their talents.

It’s not just a new asset for the performing arts. It enriches the city where both were born and where they stayed to make good use of their “enormously successful” investment.