The story of the phoenix is one of rebirth. A mythical creature self-destructs in a flaming blaze. Then it rises from the ashes. The immortal mythology resurrects again and again in literature, from ancient civilization into the modern-day. Add to that symbolic tradition the new biography of John Fife Symington III: Old Money, New West: Fife Symington and the Uniquely American Landscapes That Made Him, Broke Him, and Made Him Anew, written by Robert Nelson and Dr. Jack L. August.

br

Symington was a Phoenix real estate developer turned-neoconservative luminary whose bright political career collapsed under federal prosecution. The second-term governor of Arizona resigned and packed for prison before a federal court of appeals overturned his convictions. Even so, the possibility for ambitious attorneys to refile charges against the wealthy Symington remained—until the waning hours of Bill Clinton’s final day in the Oval Office, when a rare “preemptive” presidential pardon spared Symington from another criminal trial and risk of hard time.

br

Nelson, a former Omaha Magazine editor and Omaha World-Herald columnist, coauthored the expansive 488-page book with August, a prolific biographer of influential Arizonans. August was the Arizona State Historian and worked at the Arizona Capitol Museum when he died in 2017. A few years earlier, the historian convinced Symington to cooperate on the biography project. August also discovered a treasure trove of his gubernatorial records, lost for 20 years in the commotion of Symington’s hasty resignation from office.

br

Nelson took over the book after August’s death. It was an intense research effort for both men. Independently, they each spent hundreds of hours combing through archival records and conducting interviews with Symington and contemporaries. Nelson revised August’s first-draft chapters on family genealogy, and he expanded the project into a 42-chapter narrative from his current residence in the rural outskirts of Washington, D.C., with frequent work trips to Phoenix—on top of regular visits back to see family in Nebraska.

br

The biography covers Symington’s ancestral lineage up to the present day. The great-grandson of robber baron steel magnate Henry Clay Frick grew up in a wealthy Maryland family. His father was U.S. Ambassador to Trinidad and Tobago during the presidency of Richard Nixon, and his cousin was a U.S. Senator from Missouri. Arizona senator and presidential candidate Barry Goldwater (considered the “ideological godfather of the modern Republican Party”) was a close family friend.

br

A child of East Coast privilege, Symington graduated from Harvard with a degree in Dutch art history. He received the Bronze Star in the Air Force during the Vietnam War, then reinvented himself as a hotshot commercial real estate developer in Phoenix during the booming 1980s—before the market collapsed with the Savings and Loan Crisis. In the 1990s, he ventured into politics. Symington became a conservative iconoclast advocating for government to be run like a business. As governor, he not only balanced the state’s budget but created a surplus. In the process, Symington gained nationwide prominence. That’s when errors of bookkeeping from his real estate career—or defrauding investors, depending on your legal perspective—came back to haunt him.

br

In 1996, Symington faced 21 federal charges of extortion, making false financial statements, and bank fraud. Was he really guilty of all seven convicted counts of bank fraud (overturned on appeal)? Or was he a scapegoat for deeper systemic problems in federal regulation of thrift banking institutions? Symington always pled innocence, and in cases of uncertainty, the authors let facts speak for themselves.

br

Former President Bill Clinton read the entire book in final-proof stage over a single weekend as the manuscript approached a September printing deadline with Texas Christian University Press. Clinton had already written one introduction for the manuscript several months prior, but he scrapped it for a new draft days before the press run.

br

The final draft detailed how he met Symington in college. They became friends despite religious, political, and socioeconomic differences: “In today’s culture, where disagreement so often seems to require personal disapproval and distancing, we might not have gotten to know each other. But I liked him. He was neither affected nor arrogant, and seemed as curious about my life as I was about his,” Clinton wrote.

br

In their next encounter, Symington saved Clinton’s life. He jumped into the Nantucket Sound to rescue the future president from drowning in a riptide. Their years in political office later overlapped, and they had amicable interactions despite widely divergent political beliefs.

br

“I’m sure more than one Republican told him he should have let me drown. I used to kid him about it, too,” Clinton wrote in the book’s introduction. “When Fife’s legal troubles derailed his life and led to the loss of the governorship, he applied for a pardon and I decided to grant it. Not because of the long-ago rescue, but because the court of appeals had reversed his conviction due to the improper dismissal of a juror.”

br

In a Sept. 5 text message to Nelson, Clinton described the book as “a master class in old fashioned journalism, stating the facts as you know them without resorting to the clickbait of shooting the wounded while presuming moral superiority.”

br

Along with Clinton and Goldwater, there are several high-profile cameos in the book’s pages. Cult filmmaker John Waters of Pink Flamingos fame was a childhood friend in Maryland, and self-proclaimed “dirty trickster” Roger Stone schemed against Symington’s first foray into gubernatorial politics. Three decades later, Stone—who has President Nixon’s smiling face tattooed on his upper back—was convicted of obstruction, making false statements, and witness tampering during Donald Trump’s impeachment investigation. President Trump issued a full pardon of Stone before leaving office in 2020.

br

As a work of modern political scholarship, Symington’s biography offers key insights to the Republican Party’s transformation during the Gingrich Revolution of 1994. The historic midterm election year saw Republicans gain majority control of the U.S. House, U.S. Senate, state legislatures, and state governorships—that included Symington, who succeeded as incumbent to his second term as Republican governor of Arizona.

br

Symington’s fall from grace and personal recovery follows a story arc similar to Nelson’s own struggles. Rather than legal or financial trouble, however, the Nebraskan writer fell into a downward spiral of worsening health: chronic pain, depression, a crippling stroke, and alcoholism.

br

“It felt like I was broken in most every way you can be broken,” Nelson said, speaking via Zoom video call from his home office in northern Virginia. “At the bottom there, about a decade ago, I was pretty sure I’d never write a coherent sentence again, let alone some big-ass book.”

br

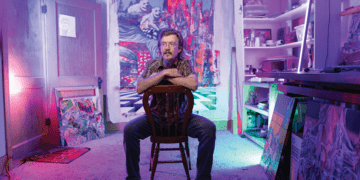

The walls surrounding his desk look like a weird autobiographical assemblage. There is a black custom-made guitar from Vietnam with Abraham Lincoln’s face; a funky portrait of Nelson painted by a Bulgarian artist; an original cartoon by The Simpsons creator Matt Groening; a certificate confirming his status as Admiral in the Great Navy of Nebraska; a University of Kentucky baseball calendar featuring his oldest son on the pitcher’s mound; and a cover proof of Symington’s biography.

br

If he has lingering brain damage—and he has seen the post-stroke MRI scans that offer proof—it doesn’t show in conversation. He talks fast with characteristic wit and often-deviant humor that longtime Omaha readers would recall from his award-winning newspaper columns in the World-Herald, published between 2007 and 2012.

br

No overt references to mythical phoenixes appear in Symington’s biography—aside from the eponymous Arizona city where much of the book takes place. As a matter of historical fact, American settlers developed the modern metropolis over abandoned remnants of the ancient indigenous Hohokam civilization, which had long before used the Salt River to irrigate the valley around 300-1500 A.D. Symington’s real estate career contributed landmark structures to the city, with the luxurious Camelback Esplanade a prime example. The development went on the market as the Savings and Loan Crisis collapsed rental rates, leading to millions of dollars lost (contributing to the governor’s later legal woes).

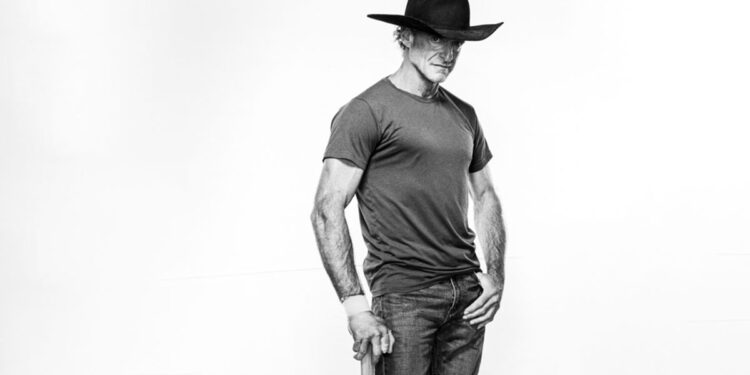

Photo by Bill Sitzmann

br

A true journalist, Nelson doesn’t interject his personal narrative in the book. In fact, he has never written about the circumstances surrounding the end of his thrice-weekly World-Herald column. It remains a tender subject in his memory. But he did discuss personal struggles with Symington over the course of their interviews. “We talked about issues of overcoming adversity and, maybe more important, powering through times of adversity,” Nelson said. “I crumbled in self-pity when faced with a portion of the troubles he waltzed through. I’m much, much more of a chin-up, grind-it-out tough guy now.”

br

Nelson grew up in the southeast Nebraska town of Falls City, which his firebrand abolitionist great-great-great-grandparents helped to establish in 1857 amid the chaotic days of Bleeding Kansas. “It’s surely a fantasy, but I’d like to imagine I’m channeling their fight-the-good-fight attitude with some of the rougher stories I’ve written over the years,” he said.

br

A summer job at the Falls City Journal inspired Nelson’s undergrad studies. He graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Journalism in 1991, then he took a writing job at the El Paso Times. He married wife Denise in Texas, where they had the first of three sons. Their growing family moved back to Nebraska for his first stint at the World-Herald on the features desk (1994-2000), before they relocated to Arizona for a long-form features job at Phoenix New Times.

br

Nelson had family living in Phoenix, and he had been watching the news there with fascination for years. “The governor had been indicted, there is a crazy sheriff running Maricopa County, and the smarmiest real estate people I knew from Omaha had moved down there,” he said. “Phoenix was a magnet for the type of people who wanted to dance around the law—or maybe exploit loose regulations—and seemed like a good place to do journalism.”

br

He dove headlong into muckraking features: for example, an exposé on the Phoenix Diocese’s protection of pedophile priests. Nelson also started connecting the dots between the abolitionist history of his native southeast Nebraska and early Arizona statehood. August, the state historian and future collaborator, became a go-to source. A few years later, August connected Nelson with Arcadia Publishing to write Early Yuma in 2006. It was Nelson’s first book.

br

The next year, the World-Herald came calling with a columnist job offer and a promise to put his face on a billboard. Nelson’s ego answered, to the dismay of his wife and kids. They did not want to move. Even so, their Phoenix home sold as the real estate market collapsed with the subprime mortgage crisis. Nelson appeared on billboards over Dodge Street and Interstate 80, on newspaper delivery trucks, and other promo ads.

br

Returning to Omaha initiated a hard lesson: Be careful what you wish for. “As a kid in Falls City who used to deliver the World-Herald, I read the paper’s columns, and to be seen like that, to be a columnist for the biggest paper in the state seemed like the coolest job. And it really was the ideal job, half of the time. The other half of the job drove me literally nuts,” he said.

br

His critical gaze turned inward to churn out first-person columns, hindered by an increasing dependence on alcohol (alcoholism runs in his family) compounded by worsening pain and depression. The newspaper’s circulation was plummeting. His online trolls seemed to be getting meaner, and he was getting angrier and more defensive.

br

World-Herald reporter Bob Glissmann edited his column. The two maintained regular contact and friendship over the years. Glissmann did not see Nelson’s time as columnist as any sort of steep decline, professionally or personally. “He always was highly productive, creative, and easy to work with,” Glissmann recalled via email with Omaha Magazine. “Maybe I was oblivious, or maybe I didn’t know him all that well, but I don’t see his trajectory as up then way down then up again. He obviously has had struggles, but from what I can tell, he always has been able to do the work.”

br

The current World-Herald staffer fondly recalled classic Nelson columns like his skewering of Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting attendees, or his critique of Arbor Day founder J. Sterling Morton as “an awful human being and arguably the worst influence on the soul of this state in our history” more than a decade before the National Statuary Hall of the U.S. Congress removed its statue of the famously racist Nebraskan. “All you had to do was plant a seed and he would water and tend to the plant and harvest it. On deadline. And he came up with plenty of good ideas on his own,” Glissmann wrote.

Photo by Bill Sitzmann

br

At the time, Nelson tried to keep his problems private. Chronic pain led to major spinal surgery in 2011 with the fusing of his C5-C7 vertebrae. All of his joints were swollen a month later. “The pain was pushing unbearable,” he said. “I was struggling to walk. There was burning in my fingers, wrists, elbows, spine, knees, and ankles.” Then came a diagnosis of severe Lofgren’s syndrome, which may or may not have been accurate. “I was taking large doses of medicines on top of Percocet. By the winter of 2012, I was sometimes drinking a fifth of vodka a day.”

br

Then came a stroke. It partially incapacitated his left side. Nelson said he struggled to read even simple sentences; memory went from bad to horrible; he developed a heavy stutter. Only Denise knew the full extent of his health problems. When Nelson finally went to a neurologist, tests showed significant cognitive impairment. “Writing the column became nearly impossible,” he said.

br

Nelson got in a fight with newsroom leadership, quit, and started driving to Arizona. He changed course and withdrew his resignation. Back in Omaha, he walked into a local treatment center to seek help. Without his permission, someone from the center called a friend at the newspaper to share the gossip—a likely HIPAA violation. Rumors spread up to World-Herald management, who then confronted Nelson. Furious at the invasion of privacy, he hung up the phone. Vacation leave became short-term disability, which turned into long-term disability.

br

Already separated on-and-off from his wife, he stayed with friends for weeks and months at a time. After wearing out his welcome, he camped in his car. Anti-depression and anxiety meds only went so far. He went to a friend’s ranch in Colorado to chop down trees killed by pine beetles and “drank the whole time.” Upon returning to Nebraska, he moved into a friend’s cabin near Fremont. An extended binge followed, and the memories go fuzzy.

br

“I had passed out in my car one afternoon in late April,” Nelson said. “A deputy knocked on the window, and I end up with a DUI because my keys were within reach. After spending the night in a Saunders County jail in Wahoo, Denise bailed me out. I didn’t think she would. It was a big enough shock to get me to fight the alcoholism. My brother drove me up to the Valley Hope facility in O’Neill the following Monday. Was there for a month. It was as awful as it was transformative.”

br

Nelson began attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, even serving on a district board. “I went from the Rotary circuit to the AA circuit,” he said with a laugh. He started exercising more, coaching baseball again, healing with his family. The mental fog began to clear. Sober a few years, he got off disability and started pursuing a teaching degree. That’s when he noticed a managing editor job opening at Omaha Magazine. So, he called up publisher Todd Lemke.

br

“He was very up front about his past problems,” Lemke said, recalling Nelson’s job application. “He promised that it was behind him and he was looking forward to continuing his passion for journalism.” The publisher had enjoyed reading Nelson’s newspaper column and was unaware of the circumstances surrounding his departure. “It took me aback. I thought about it, then gave him a call to say let’s give it a try.”

br

After two years and a slew of awards from the Great Plains Journalism Awards, Nelson left the magazine in 2015 (though he briefly returned as the interim executive editor during a 2016 editorial leadership transition). Lemke and team were sad to see him go. But his wife, Denise, had a once-in-a-lifetime job promotion in the National Park Service. “Guarding more than 2,000 miles of the Appalachian Trail for Americans was something she couldn’t pass up,” Nelson said. “And she had suffered so much with me, honestly, moving three times. It was her turn.”

br

Their youngest was in eighth grade, their middle child was studying engineering in college, and their oldest was playing NCAA Division I baseball. Nelson started writing for Virginia Living Magazine, and he launched a new publishing company, Legacy West Publishing (unrelated to the Symington biography), with his longtime Arizona history collaborator, August.

br

“I became Mr. Mom” and loved every minute of it, he said. Then his autoimmune dysfunction resurrected. Joint swelling returned. He had to sleep sitting up or his hands would go numb and start burning. A new diagnosis: ankylosing spondylitis. Self-medication with alcohol was not part of treatment this time. New meds and a strict exercise regimen facilitated a return to normalcy. On top of daily weight-lifting, he volunteered axe-swinging muscle to clearing fallen trees from the Appalachian Trail near their home. “I have to exercise now. Otherwise, it is too painful to write,” he said.

br

Photos from his personal Facebook feed reveal chiseled shoulders, pecs, and biceps on his lean 50-something-year-old frame. Yet he jokes about his “misshapen body” with self-deprecating modesty, attributing the veins bulging from his muscles to prescribed prednisone.

br

After settling into his new routine, Nelson received a phone call from August. The historian was struggling with several major projects, including the Symington biography (financed by the Southwest Center for History and Public Policy, a nonprofit that August had established with an independent board and rigorous peer-review protocols). Nelson started flying out to Phoenix to assist. He soon noticed his brilliant friend and mentor seemed to be drinking more than in years past. On a few occasions, Nelson discussed his own battle with alcohol; the sober writer still regrets not suggesting his former drinking buddy seek help. In early 2017, Nelson received a call from a mutual friend: August had passed away due to liver failure.

br

August’s wife and the nonprofit center’s board of directors knew of Nelson working with the historian. They hired him to complete the mostly unwritten Symington biography. Nelson proposed coauthorship for the book’s cover and will split royalties with August’s widow.

br

In the finished book, Symington’s post-pardon rehabilitation features an admission to witnessing the UFO event known as the Phoenix Lights. There is also Symington’s rebirth as an acclaimed pastry chef and culinary entrepreneur (with his baked goods on sale in the luxurious Camelback Esplanade, a development so prominent in his misfortunes). More recently, there is also the irony of a famously tough-on-crime governor (who once threatened to overturn a successful voter petition approving the legalization of medical marijuana) becoming a major investor in his son’s industrial-scale marijuana farm.

br

Nelson finished writing the book amid the pandemic. Symington caught COVID-19 and recovered. The immunocompromised Nelson was quick to be vaccinated. But that didn’t stop pandemic closure of the Phoenix archive where the writer made a last-minute trip to gather photos for publication.

br

What was Symington’s feedback on the book? Defensive at first. But he called in early September before heading on a trip to Alaska to voice a more favorable opinion. “He was feeling pretty beat up when we walked through it the first time,” Nelson said. “[Symington] really did come to terms with the idea that once I’m detailing his time in the public sphere, his detractors needed equal time to present their counter arguments.”

br

The biography is scheduled for release in December 2021, with preorders being filled in early November. Meanwhile, Nelson has a new book project in the works, the story of another individual risen from the ashes of a former life—Dennis Ryan.

br

Ryan was sentenced to life in prison for a murder-torture he was involved with when he was 15 years old, convicted alongside his Doomsday cult leader father, Michael Ryan. Nelson went camping with the younger Ryan after his release from prison in 1997, and he has written several stories about Ryan overcoming his father’s demonic shadow for publication in both the World-Herald and Omaha Magazine. Michael Ryan died on Nebraska’s death row in 2015.

br

“This might sound a little weird to Nebraskans, but of the people in pretty close orbit in my life, it’s Symington and Dennis Ryan who have provided two of the more impactful models for how to gracefully navigate what look like insurmountable hurdles,” Nelson said.

br

Journalist and sources alike found new life flickering, burning out of their darkest hours.

br

Author’s note: Nelson was managing editor at Omaha Magazine when I began contributing to the publication as a freelancer. After an unexpected change in senior editorial leadership during 2016, Nelson returned to Omaha as the magazine’s interim executive editor while recruiting the next top editor. I held the position on staff at the magazine from 2016-2019.

br

Visit tamupress.com for more information and to order a copy of the book.

Photo by Bill Sitzmann