Listen to this article here. Audio Provided by Radio Talking Book Service.

On Monday nights, the North Omaha Music and Arts near 24th and Lake streets becomes a magnet for multi-generational jazz talent, featuring a lineup that’s worked with some of the most trailblazing icons in contemporary music. At no cover charge, attendees are introduced to seasoned artists who’ve played for Wynton Marsalis, jammed at Lauryn Hill’s house, and toured for national Broadway shows. Open mic kicks off around 7pm. About an hour later, eager young musicians are invited to hone their chops.

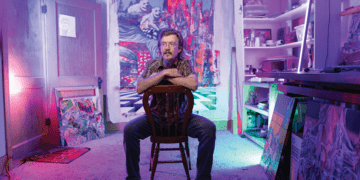

For the “pro” set, Dana Murray—executive director of North Omaha Music and Arts—usually sits behind the drums. For Jeff Jenkins, it’s behind the ivory keys.

On a warm Tuesday evening in June, Jenkins strolled into NOMA looking the part of a jazz pianist. Wearing a dark blue plaid blazer, a black pork pie hat, and sporting a neat goatee, Jenkins watched with anticipation as fellow musicians set up for the night’s session.

Born in Hebron, Nebraska, Jenkins and his family moved to Nebraska City when he was 2 years old. His father, Bill, a trumpet player, was a high school music director. He encouraged the young Jenkins to play trombone, but it was his mother, Ellie, who taught him piano. More than 50 years later, Jeff’s son, Ellington (named after famous jazz pianist Duke Ellington), still has the Baldwin Acrosonic piano that Jeff learned to play on when he was 4.

After graduating from Nebraska City High School, Jenkins spent two years at Midland Lutheran College in Fremont when his father sent him to the Jamey Aebersold jazz camp in Kansas. While there, he met composer and jazz pianist Dan Haerle, who encouraged Jenkins to finish his schooling at the University of North Texas.

“At that point, that was one of probably a half-dozen places in the country where you could actually study jazz,” Jenkins recalled.

Jenkins followed Haerle’s advice, earning his Bachelor of Arts in jazz performance before spending time in Dallas to learn the ropes of live gigs. In 1983, he decided to move to New York City. He sold the piano he had in Dallas to buy a new one in New York, and braced himself for intense competition.

“People are nice in New York, but they’re brutally honest,” Jenkins said. “If you’re not cutting it, they’ll tell you.”

During his first year in New York, Jenkins didn’t perform for audiences. Living off his savings, he focused exclusively on practice. Putting a piano in a New York studio apartment meant sleeping beneath it atop a rolled-out futon mattress.

“I thought it was romantic and cool. Now, I wouldn’t think that,” Jenkins laughed.

Jenkins’ first big break came with the off-Broadway musical Little Shop of Horrors in 1984. After filling in for a friend in the off-Broadway version, Jenkins was hired to play keyboards for the national tour. For two years, he traveled throughout the United States. When he returned to New York in late 1985, he took over the keyboard position for the New York production of Little Shop of Horrors. As one of the most successful off-Broadway productions in New York City’s history, the coveted slot offered both financial stability and musical credibility.

In 1990, Jenkins moved to Denver, Colorado, to be with his then-wife. Even though Jenkins was no longer living in New York City, he continued to encounter some of the most influential figures in jazz, including Bobby Hutcherson and Freddie Hubbard. Along with playing festivals, Jenkins was part of a music ensemble that opened for David Byrne at the world-famous Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

In 2008, Jenkins joined the faculty of the University of Colorado at Boulder as a jazz studies professor. In addition to teaching, Jenkins ran his own recording studio, Mile High Music. Brad Goode, a trumpet player and an associate professor of jazz studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder, recorded his album Chicago Red at Jenkins’ studio. Jenkins plays keyboards on Goode’s latest album, The Unknown, which was released this year. During a Zoom interview, Goode said Jenkins’ deep knowledge of jazz extended to other genres, like Latin music and Broadway musicals.

“He’s not a ‘dabbler’—he’s an expert in so many different areas of music,” Goode noted.

Jenkins moved to Omaha in August 2022 with his wife, singer Terri Jo Jenkins. This past spring, he retired from the University of Colorado. He cited his health as one of the main reasons he chose to retire. He was diagnosed with Adrenomyeloneuropathy, or AMN—an inherited genetic disorder that affects the spinal cord, requiring Jenkins to use a cane.

Growing restless in his first year of retirement, Jenkins began playing at The Jewell in Omaha’s Capitol District, where he caught the eye of drummer and music producer Dana Murray. In addition to the Monday night sessions, Jenkins teaches a jazz improvisational class at North Omaha Music and Arts.

“There’s a soul and organic nature about how he plays,” Murray said.