Listen to this article here. Audio Provided by Radio Talking Book Service.

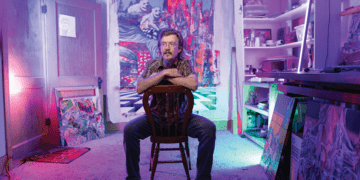

After finding fame, few Nebraska Hollywood talents have historically made their native state home. Filmmaker Alexander Payne, coming off a busy fall promoting his popular new dramedy, “The Holdovers,” starring Paul Giamatti, maintains an Omaha residence and has shot all or part of five of his eight feature films in state.

The two-time Oscar-winner welcomed warm receptions to “The Holdovers” at film festivals in Telluride (where it garnered the People’s Choice runner-up), Toronto, and London. Then, he did press for limited and wider theatrical releases, finally returning home for a Film Streams fundraiser in mid November.

With audiences and critics falling for the Christmas-themed film, he hopes award love follows. Veteran television producer-writer David Hemingson (“Whiskey Cavalier;” “Kitchen Confidential”) is a Best Original Screenplay Oscar contender for his sweet-and-sour story about three misfits harboring deep hurts who are forced to spend Christmas together.

Shot in and around Boston, the film is set in 1970 at a New England boarding school. Hated history teacher Paul Hunham (Giamatti) must babysit smart-aleck student Angus Tully (newcomer Dominic Sessa), who’s been ditched by his mother and step-father. Completing the trio is knowing school cook Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), grieving her son’s death in the Vietnam War. Their funny, painful bonding plays out on campus and during a memorable “field trip.”

Giamatti, who starred in “Sideways,” is netting career best notices in a lead written for him. Randolph and Sessa are garnering praise for their strong supporting work. Payne’s sure direction may also help “The Holdovers” be a Best Picture nominee.

Payne’s longtime editor Kevin Tent cut the “The Holdovers,” but he collaborated for the first time with Danish cinematographer Eigil Bryld and production designer Ryan Warren Smith. Tent’s hand is felt in the film’s gentle transitions and smooth flow, while Bryld and Smith’s work contribute to the authentically rendered world its characters inhabit.

The praise greeting the film is bittersweet for those involved. The SAG strike prevented Giamatti, Randolph, and Sessa from joining Payne at premieres and press conferences, and representing the film by himself has been disappointing and exhausting, he lamented.

Post-production wrapped a year ago. Keeping the film in reserve until now ensured a holiday buildup. After all, Payne said, “It is a Christmas movie.” Still, this holding pattern felt like another detour for the writer-director, who’s endured setbacks since “Downsizing” left both audiences and critics cold in 2017. That broke a string of critical acclaim from “Citizen Ruth” (1997) through “Nebraska” (2013). In the ensuing six years, he saw intended projects fall apart. The pandemic didn’t help.

It’s not the first long span between Payne films. The filmmaker’s deliberate process, Tent said, “involves extended prep work–he never rushes into a project until he feels it’s ready, and I think the reason his movies are so good is exactly because of that.”

While frustrated by career snags, Payne balked at the notion that he needs a success to recapture any lost mojo.

“I’ve never actively aspired to ‘hits.’ I never thought I’ve made those kinds of movies,” he said. “Sure, I want them all to be ‘successful’ on their own terms–well-made, well-considered, well-acted, well-told stories that people want to see and make more money than they cost.”

The idea for the story originated with Payne. He entrusted Hemingson specifically to develop the script about the reluctant holdovers. As a graduate of an Eastern prep school himself, Hemingson is well-versed in that culture.

Giamatti, too.

“I would have wanted Paul to play this regardless, but him knowing that world added to his performance. This just felt like a very good part for him,” said Payne, who wanted Giamatti from the jump.

In turn, Hemingson wrote with Giamatti in mind. Payne gave him relatively free rein.

Hemingson suggested several ways the story could unfold. “He started giving me pages and eventually a whole draft, and then I would…give him suggestions, both big and small,” Payne shared. “We would discuss those or execute those. It just kept evolving. I’ve directed every other department, but with David it was my first experience directing a writer, and we had a really good relationship and a good time doing it.”

Hemingson didn’t mind being the student to someone he regards “a master” for his “emotionally resonant comedy penetrating inside the human condition.”

“Alexander was able to push me in certain directions as I was writing,” Hemingson said. “That was invaluable. It was mostly him posing questions and then me giving him a result. It was very much a conversation. Sometimes [we were] on the phone when he was in Greece or in Omaha. Sometimes we’d hang out at his place or at mine, have dinner and a glass of wine, and hash it through.”

Hemingson did rewrites on set. “There were times I had to adjust the screenplay this way or that based on a location or a certain actor…and he was always available—even just to have someone around to talk it through with,” Payne said.

With “The Holdovers,” Payne set out to channel the humanism of ‘70s American films. Critics say its whimsy, irony, and character-based truth may make it the best ‘70s film made outside that decade.

He’s also created a film that may stand the test of time with other Christmas favorites. The prospect of “The Holdovers” becoming a holiday staple pleases Payne.

“That’s a lovely thought.”

For more information about Alexander Payne’s latest movie, visit

miramax.com/movie/The-Holdovers.

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2024 issue of Omaha Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Listen to this article here. Audio Provided by Radio Talking Book Service.

After finding fame, few Nebraska Hollywood talents have historically made their native state home. Filmmaker Alexander Payne, coming off a busy fall promoting his popular new dramedy, “The Holdovers,” starring Paul Giamatti, maintains an Omaha residence and has shot all or part of five of his eight feature films in state.

The two-time Oscar-winner welcomed warm receptions to “The Holdovers” at film festivals in Telluride (where it garnered the People’s Choice runner-up), Toronto, and London. Then, he did press for limited and wider theatrical releases, finally returning home for a Film Streams fundraiser in mid November.

With audiences and critics falling for the Christmas-themed film, he hopes award love follows. Veteran television producer-writer David Hemingson (“Whiskey Cavalier;” “Kitchen Confidential”) is a Best Original Screenplay Oscar contender for his sweet-and-sour story about three misfits harboring deep hurts who are forced to spend Christmas together.

Shot in and around Boston, the film is set in 1970 at a New England boarding school. Hated history teacher Paul Hunham (Giamatti) must babysit smart-aleck student Angus Tully (newcomer Dominic Sessa), who’s been ditched by his mother and step-father. Completing the trio is knowing school cook Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), grieving her son’s death in the Vietnam War. Their funny, painful bonding plays out on campus and during a memorable “field trip.”

Giamatti, who starred in “Sideways,” is netting career best notices in a lead written for him. Randolph and Sessa are garnering praise for their strong supporting work. Payne’s sure direction may also help “The Holdovers” be a Best Picture nominee.

Payne’s longtime editor Kevin Tent cut the “The Holdovers,” but he collaborated for the first time with Danish cinematographer Eigil Bryld and production designer Ryan Warren Smith. Tent’s hand is felt in the film’s gentle transitions and smooth flow, while Bryld and Smith’s work contribute to the authentically rendered world its characters inhabit.

The praise greeting the film is bittersweet for those involved. The SAG strike prevented Giamatti, Randolph, and Sessa from joining Payne at premieres and press conferences, and representing the film by himself has been disappointing and exhausting, he lamented.

Post-production wrapped a year ago. Keeping the film in reserve until now ensured a holiday buildup. After all, Payne said, “It is a Christmas movie.” Still, this holding pattern felt like another detour for the writer-director, who’s endured setbacks since “Downsizing” left both audiences and critics cold in 2017. That broke a string of critical acclaim from “Citizen Ruth” (1997) through “Nebraska” (2013). In the ensuing six years, he saw intended projects fall apart. The pandemic didn’t help.

It’s not the first long span between Payne films. The filmmaker’s deliberate process, Tent said, “involves extended prep work–he never rushes into a project until he feels it’s ready, and I think the reason his movies are so good is exactly because of that.”

While frustrated by career snags, Payne balked at the notion that he needs a success to recapture any lost mojo.

“I’ve never actively aspired to ‘hits.’ I never thought I’ve made those kinds of movies,” he said. “Sure, I want them all to be ‘successful’ on their own terms–well-made, well-considered, well-acted, well-told stories that people want to see and make more money than they cost.”

The idea for the story originated with Payne. He entrusted Hemingson specifically to develop the script about the reluctant holdovers. As a graduate of an Eastern prep school himself, Hemingson is well-versed in that culture.

Giamatti, too.

“I would have wanted Paul to play this regardless, but him knowing that world added to his performance. This just felt like a very good part for him,” said Payne, who wanted Giamatti from the jump.

In turn, Hemingson wrote with Giamatti in mind. Payne gave him relatively free rein.

Hemingson suggested several ways the story could unfold. “He started giving me pages and eventually a whole draft, and then I would…give him suggestions, both big and small,” Payne shared. “We would discuss those or execute those. It just kept evolving. I’ve directed every other department, but with David it was my first experience directing a writer, and we had a really good relationship and a good time doing it.”

Hemingson didn’t mind being the student to someone he regards “a master” for his “emotionally resonant comedy penetrating inside the human condition.”

“Alexander was able to push me in certain directions as I was writing,” Hemingson said. “That was invaluable. It was mostly him posing questions and then me giving him a result. It was very much a conversation. Sometimes [we were] on the phone when he was in Greece or in Omaha. Sometimes we’d hang out at his place or at mine, have dinner and a glass of wine, and hash it through.”

Hemingson did rewrites on set. “There were times I had to adjust the screenplay this way or that based on a location or a certain actor…and he was always available—even just to have someone around to talk it through with,” Payne said.

With “The Holdovers,” Payne set out to channel the humanism of ‘70s American films. Critics say its whimsy, irony, and character-based truth may make it the best ‘70s film made outside that decade.

He’s also created a film that may stand the test of time with other Christmas favorites. The prospect of “The Holdovers” becoming a holiday staple pleases Payne.

“That’s a lovely thought.”

For more information about Alexander Payne’s latest movie, visit

miramax.com/movie/The-Holdovers.

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2024 issue of Omaha Magazine. To subscribe, click here.