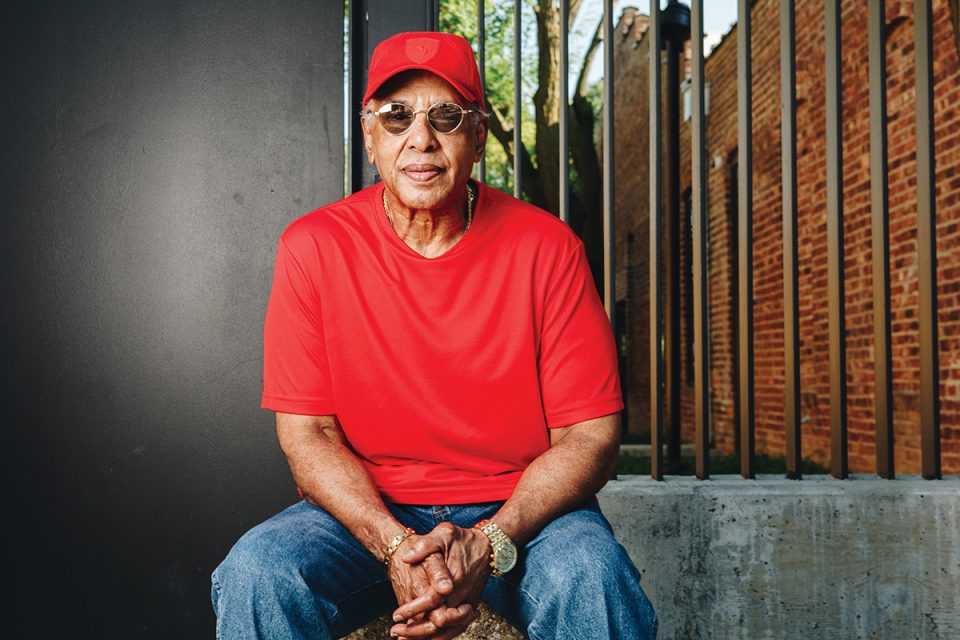

If Curly Martin has something to say, you can best believe you will hear it if you’re within earshot.

“Man, tell me who came up with this idea for a story about the Chitlin’ Circuit, I know it had to be a white boy,” Martin says during a boisterous conversation. “First, make sure he gets it straight; it’s not chitterlings. It was called the Chitlin’ Circuit!”

While chitterlings—chitlins for short—are a soul-food staple made from the small intestines of pigs, the Chitlin’ Circuit refers to venues in the South (and into the Upper Midwest) that supported traditional rhythm and blues acts. Martin finds the term as repulsive as its namesake.

“I know they think the Chitlin’ Circuit was for the mediocre musicians, but let me tell you, the Blues and R&B Chitlin’ Circuit was different from the Jazz Chitlin’ Circuit. Jazz players ruled Omaha and always stayed sharp. We dressed like pimps and players because that was our clientele.”

There are still jazz heavyweights living on Omaha’s northside, and Martin is testament to the fact. In the music room of his modest home, nestled near Belvedere Point, he collects an assortment of recording equipment and memorabilia: a 1972 Fender Rhodes keyboard, albums worked on with smooth-jazz innovator Grover Washington, and an award for the 2017 Best Jazz Musician in Omaha from the Omaha Entertainment and Art Awards.

“They told me I would have to pay to pick it up, but somehow it wound up here,” he says of the OEAA award. 2017 was an eventful year for Martin. In addition to the local award, he was also nominated for a Grammy for Best R&B Album alongside his world-renown, West Coast producer/songwriter son, Terrace Martin.

“Grammy-nominated for Velvet Portraits and Homer’s didn’t even have the album,” Martin recalls. “I brought Terrace to Make Believe Recording Studios to record that album, but these fools in Omaha won’t acknowledge it! There’s even a song named ‘Curly Martin’ my son did with Robert Glasper. Now that’s a tough tune.”

When asked if there are remnants of the jazz scene he once knew in Omaha, Martin scoffs.

“The ‘decision-makers’ on the music scene don’t like me because I’ll tell them to their faces they can’t play,” Martin states unapologetically. “I don’t think Omaha artists have enough range, and they’ll get mad at me for telling them the truth!”

One of the few people Martin considers an ally is Kate Dussault, founder of the Hi-Fi House. After hosting a series of successful Jazz Labs with Martin, she acknowledges him as an unappreciated artist in the local music scene.

“Curly is a hoot, but he is passionate about passing his knowledge on to the younger generation,” Dussault says. “He is more akin to a mentor than an academic teacher. I can recall him saying that you can go to class all day and do your homework, but where is the inspiration?”

“They don’t even know that I sold out the Holland Center back in February, man,” Martin asserts. “I brought out some of the best guitarists in the world that still reside in North Omaha like Wali Ali and Calvin Keys or saxophonist Hank Redd. These guys have worked with The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and Tony Bennett. Musicians around here aren’t as diverse as we were, so they can’t compare to back in the day.”

Martin goes on to describe the Jazz Circuit lifestyle: thousand-dollar diamond rings, mohair suits, and alligator shoes that had to match the belt. They would play seven days a week traveling between the Blue Note in Minneapolis, Allen’s Showcase in North Omaha, O.G.s in Kansas City, KC Lounge in Denver, and the BTW Hotel and Lounge in San Francisco.

“Man, we rotated through those clubs throughout the ’60s,” Martin reminisces. “Mr. Allen at the Showcase let a lot of us jazz players get our feet wet, but there was also Alice’s Lounge, Shirley’s, and the Black Orchid in North Omaha. Even for the white folks, if they wanted to hear the baddest of the bad they had to come to the northside and downtown!”

Morning breakfast dances from 6-10 a.m. on holidays, Sunday jam sessions, and good music playing on every corner is the North Omaha jazz mecca that Martin remembers.

“I was probably 14 when I started drumming for my first band, Daddy Long Legs and the Rocking Nighthawks. I even had a gig downtown at Mickey’s with a checkerboard band called Danny and the Roulettes because mixed-race bands were popular. We were jamming downtown when the so-called riots of ’69 went down. After that uprising, our era started to wind down.”

These days, Martin focuses on the future. With a new album in the works and another project with Dussault upcoming, he is eager to give back to his community.

“They tried to get me involved with WeBop, but I’m not trying to be a babysitter,” Martin says, referring to the early childhood education program. “I want to get kids when they’re serious about their craft, and show them that North Omaha has a rich background. I can’t let them bury our history; this generation can see me and say, ‘If Curly lived this wonderful life then I can do it, too.’”

https://youtu.be/5ElO35WfnZM

Terrace Martin produced Velvet Portraits and is producing his father’s upcoming album. Follow @terracemartinmusic on Facebook for updates.

This article was printed in the July/August 2018 edition of Omaha Magazine.