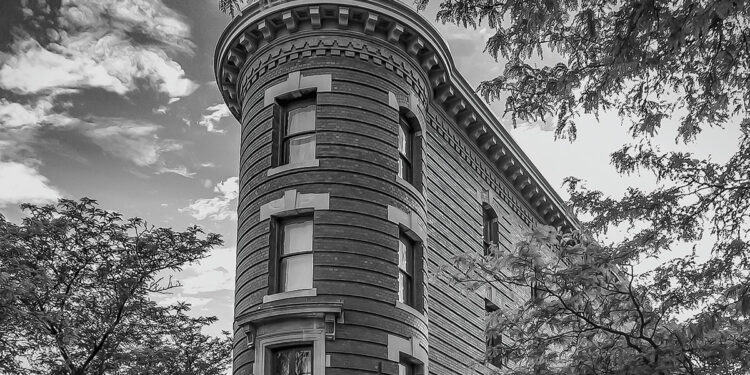

Omaha’s iconic Flatiron building had a wonderful beginning. An article in a January 1912 edition of the Omaha Daily Bee previewed the eagerly anticipated spring opening of the building designed to fit the odd triangular lot created where St. Mary’s Avenue intersects Howard Street between 17th and 18th streets.

Inspired by New York City’s 22-story Flatiron Building that opened a decade earlier, banker and landowner Augustus F. Kountze envisioned a similarly shaped, four-story Georgian Revival building. Architect George Bernhard Prinz, whose works included the Livestock Exchange Building and the Tudor-revival style clubhouse at Omaha Country Club, designed Omaha’s Flatiron; and J.C. Mardis Co. (builder of Vinton School and multiple hotels) was named as builder.

The first-floor commercial and office space, the Daily Bee article said, would provide “exceptional opportunities and advantages for high-class retail merchandising.” The building’s three upper floors would be designated for “guests of the best class.” Omaha Daily News ads boasted 96 rooms and 30 baths, with rents starting at $18 per month.

It wasn’t long before someone realized the building was perfect for a restaurant. By December 1912, according to the Omaha Daily Bee, Ida Cooke opened the building’s first cafe. The first Flatiron Cafe would be one of several restaurants to operate on the building’s west end over the next 110 years, including the Hayden House in the 1950s and, eventually, the modern incarnation of the Flatiron Cafe that Steve and Kathleen Jamrozy opened in 1995.

By the time the Jamrozys were considering the site, the building had gone through some rough times. It was repeatedly plagued by flooding that was only somewhat alleviated by a 1921 grading project and was finally being addressed in the mid-1990s. It deteriorated in the 1960s and 1970s; a 1977 photo from the Durham Museum’s archives shows a rooftop sign missing an “L” (reading “Fatiron.”) Benjamin Wiesman of Wiesman Development stepped forward to preserve and renovate the iconic building, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

“As loved as our Flatiron Building is, there were a number of times it was slated for the wrecking ball,” Kathleen Jamrozy said. “Fortunately, the Wiesman family in the ’80s saw the potential there and they put a lot of money into refurbishing it for offices. They also did the work to get it on the national historic register.”

To modern consumers, a “flatiron” is a tong-like cosmetic device that straightens hair. A “flatiron” 100 years ago was a clothes iron, made of cast iron with a tall triangular chamber underneath for users to insert coal to heat the press plate. Builders of several dozen Flatiron buildings (by official or colloquial name) in the U.S. must have seen majesty in the design.

“As you are approaching the building, there is a sense—it’s almost like the prow of a ship,” Jamrozy said. She’s visited the Flatiron buildings in NYC, Chicago, and San Francisco, and restaurant patrons sent postcards from Flatiron buildings all over the world. “[Those were] always a delight to receive.”

Jamrozy found the less-documented past of the building intriguing, she said. Historical rumor has it that the hotel was a haven for mobsters in the 1930s, including the infamous Al Capone, who was associated with Omaha’s crime boss Tom Dennison.

“We always joked that there was ‘mobster dust’ we cleaned off the ledges,” Jamrozy said. “There is a charm to the mythology of it.”

Although the original vision was to open a casual dining restaurant elsewhere in the city, the Jamrozys felt the proximity to the Orpheum and the downtown hotels was better suited to fine dining.

“Certainly, we were a destination restaurant,” Jamrozy said. “But it was also a place where people would come and park and have dinner, and then be able to stroll downtown, which I always felt was such a plus.”

“It was our absolute favorite place to eat for years and years. We ate there every time we attended Orpheum events—every few months—and had lots of special-occasion dinners,” former patron Gary Glissman said. “The Flatiron definitely had some of the best food, service, and atmosphere of any restaurant in Omaha.”

“People would come in and feel special every time they visited,” Jamrozy said. “Hospitality was our brand.”

Jamrozy couldn’t see the brand working for indefinite carryout service when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The Flatiron Cafe closed in 2020. The building hosted a series of pop-ups by restaurauteur Nick Bartholomew in summer 2021, and in October last year it was announced that Omaha’s second Dirty Birds location would move in this year.

“What’s important is that the Flatiron has held many stories,” Jamrozy said. “The building has a long history and, God willing, it will have a long history ahead.”

Visit hotelflatiron.com for more information.

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Photo by Steve Kowalski, A Better Exposure